Key Points

-

Details the importance of a thorough comprehensive consultation for chronic facial pain patients.

-

Highlights the factors that determine overall patient satisfaction with treatment for various facial pain conditions.

Abstract

Objective The aim of this audit was to investigate complex chronic facial pain patients' satisfaction after an initial, comprehensive, 45-60 minute consultation visit.

Design Prospective audit using a post-visit satisfaction survey.

Setting Specialised outpatient facial pain unit.

Methods A convenience sample of 50 consecutive new patients were recruited. History, pain and psychosocial functioning were assessed through standard, validated pre-visit questionnaires. A post-visit satisfaction questionnaire was sent (twice if necessary) to patients by mail, and non-responders were contacted by telephone.

Main outcome measures Patients' satisfaction scores on pain management processes were evaluated.

Results Response rate for the questionnaire was 63% (32/50) and 12 additional patients who did not respond to the questionnaire replied by telephone. Among questionnaire respondents, mean overall patient satisfaction was 8.1 ± 2.2 on an 11-point scale (best score 10), with no differences based on age, gender, diagnosis, length of symptoms and treatment. There was a trend of higher overall satisfaction among patients referred by dentists and specialists. Patients who had seen at least one specialist before their visit reported higher scores in understanding the reasons for their condition and what to do to treat their condition.

Conclusions A consultation with adequate time for history taking, addressing patients' goals and thorough explanation accompanied by written information, results in high satisfaction among patients with chronic facial pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The assessment of patient satisfaction has become an important concern in the evaluation of health services, with increased interest on the part of healthcare administrators, third-party payers and patient advocacy groups.1 Satisfaction surveys identify patients' evaluation of care based on their personal preferences, expectations and care realities previously experienced.2,3 Documents from the UK Department of Health, The American Pain Society and US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality stress that pain management programmes should ensure that all patients experience individualised, supportive care that recognises and manages pain, optimises function and quality of care, and thus should be evaluated by patients.4,5,6 There is evidence that chronic pain patients can be highly satisfied with their treatment despite receiving little symptom relief.7 This suggests that in this group, factors associated with the patient-provider relationship may be more influential in determining patients' satisfaction, and ultimately their clinical outcome.

The initial consultation visit must have adequate time for attaining a thorough history so that the physical, social, psychological and spiritual (ie religious traditions and beliefs, prayer, meditation) aspects of a patient's pain and health profile are ascertained.6 This allows the provider to determine a wide range of factors that influence the degree of pain, and how patients experience and interpret pain. However, time is one of the factors most conspicuously absent in primary care consultations. The British Pain Society and British Society of Oral Medicine recommends that a consultation visit of at least 45 minutes per complex patient is required to attain a proper diagnosis, build rapport with the patient and allow time for education and counselling for patients.8

The purpose of the present audit was to determine the level of patient satisfaction after an initial, extensive and comprehensive consultation visit for chronic facial pain at a specialised outpatient facial pain unit. A secondary aim was to justify the importance of longer appointment times to effectively provide care.

Methods

Patient enrollment and pre-visit data collection

We enrolled a convenience sample of 50 consecutive new patients who were referred to a specialist facial pain unit in the summer of 2009. Before all initial visits, patients were sent and asked to complete a standard series of questionnaires, the majority of which were psychometrically tested and are used routinely in pain clinics to include: demographic information; medical history; short form Brief Pain Inventory (BPI); Graded Chronic Pain Scale questionnaire (GCPS); Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD); history of present condition; and a patient treatment goal questionnaire. The in-depth questionnaire on the history of present condition asked patients comprehensive questions about their pain condition. The treatment goal questionnaire, devised by the unit's clinical psychologist, asked patients to rate the degree of applicability of 12 treatment goals and gave them the option to add three of their own goals. Patients were also encouraged to state their beliefs about their pain, their presumed diagnosis and add other comments.

Initial patient consultation visit

Initial visits at the unit comprised the following components (and approximate time): interview using a structured history and review of responses to the questionnaires (20-30 minutes); examination of the head, neck and oral cavity, and plain radiographs and blood tests if indicated (5 minutes); and diagnosis, treatment planning, patient education and counselling (20-30 minutes). All parts were entirely performed by the treating provider, which was any one of: consultant; specialist oral surgeon; or dental senior house officer. Emphasis was placed on ensuring patients' treatment goals were addressed based on their questionnaire responses. Patient education and counselling addressed patients' conditions and planned treatment modalities (ie medical, surgical, physical, adjunctive, or self-care measures) using a variety of methods that included: verbal instruction; use of visual diagnostic aids (anatomic models, diagrams, computer presentations); and materials for the patient to take home (ie pamphlets, books and medication instructions). After the patient visit, a standardised, structured letter for the patient and referring provider was formulated by the treating provider, which included a narrative of history and examination findings, with a diagnosis and outline of the treatment plan (Fig. 1).

Post-visit questionnaire

A post-visit satisfaction questionnaire was devised by the unit (Table 1), with questions taken from the British Pain Society Guidance for primary care physicians9 and a previous patient satisfaction audit carried out at another unit. Within two weeks of their visit, patients were sent the following by mail: copy of the consultation letter and post-visit questionnaire, together with a self-addressed, stamped envelope for returning the questionnaire to the unit. For those who did not return their questionnaire within two weeks after initial mailing, a repeat mailing of the same questionnaire was performed. Patients who did not respond to the second mailing after two weeks were contacted by telephone by a secretary, who asked the following questions after verifying that the patient had not returned the questionnaire by mail: 'Are you satisfied overall with the care you received (Yes/No)?'; and 'Do you have any other comments?'

All procedures were approved by the Trust Clinical Governance Unit.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were summarised with frequencies and percentages while continuous variables were summarised with means and standard deviations, as well as medians and ranges, depending upon the distribution of the data. Statistical testing was not implemented due to a small sample size with multi-level variables. All analyses were conducted in SAS® version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Demographics, diagnoses, referral patterns and treatment goals

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics are outlined on Table 2. As opposed to patients with dental pain or temporomandibular disorder (TMD), greater proportions of patients within the other categories had seen at least two or more specialists (burning mouth syndrome [BMS] – 80%; chronic idiopathic facial pain [CFP] – 40%; neuropathic pain [NP] – 57%; trigeminal neuralgia [TN] – 44%), however these differences fell short of statistical significance (p = 0.084). This was a representative sample of this unit's population when compared to 169 patients seen over a six month period (poster presentation, British Pain Society Annual Scientific Meeting 2008).

Forty-five patients (90%) completed the treatment goal questionnaire, with their responses outlined in Table 3. Five patients (10%) had written being 'pain free' among their additional treatment goals.

Patient response rate to questionnaire

Thirty-two patients (64%) returned either the first or second questionnaires by mail, whereas 12 patients (24%) were contacted by telephone, and 6 patients (12%) provided no response due to unreturned questionnaires and inability to reach by telephone. Older patients were more responsive to the mailings, with mean ages being 63.2 years (SD = 14.0) for responders to the first mailing, 48.5 years (SD = 16.6) for the second mailing, 42.8 years (SD = 12.1) for those contacted by telephone, and 43.2 years (SD = 16.2) for those with no response. There were no appreciable trends in response rates based on gender, primary diagnosis, referral source and number of specialists seen before consultation.

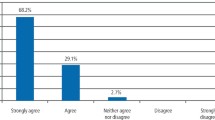

Patient satisfaction scores

Mean satisfaction scores for patients who returned the mailed questionnaires are shown in Table 1 and Figure 2. Though mean satisfaction scores were generally high, ranges for all questions were broad, with each question having at least one patient giving a low score. Among questionnaire respondents, reasons cited for low satisfaction scores were attributed to the processes surrounding their consultation visit, which included: long waiting time to appointment; arriving to cancelled appointments; missing results from previous diagnostic or imaging studies; long waiting time to receipt of visit letter by the patient and referring doctor; and not being seen by the senior staff consultant.

Among the 12 patients who were contacted by telephone, eight (67%) said that they were satisfied overall with their care, and four (33%) said that they were not satisfied, citing reasons including: feeling that the problem was not solved; disagreement over diagnosis and treatment plan; not being scheduled a follow-up appointment; and wanting more personal individual response.

Relationship between satisfaction scores and demographic and clinical characteristics

Overall patient satisfaction score (Q14) did not differ between genders (p = 0.58), diagnoses (p = 0.82) or patient disposition groups (p = 0.95). Among different referral sources, mean scores for Q14 were higher for patients referred by general dental practitioners (8.7 ± 1.3) and medical or dental specialists (8.2 ± 2.4) than they were for general medical practitioners (6.8 ± 2.5), though this was not statistically significant (p = 0.25). Furthermore, mean scores for Q14 were higher for patients who had previously seen at least one specialist (one specialist = 8.7 ± 1.3; two or more specialists = 8.2 ± 2.1) than they were for those who had not seen a specialist (6.2 ± 3.8), though this difference fell short of statistical significance (p = 0.09).

Mean scores to individual questions did not significantly differ among different diagnoses (Fig. 2). Patients who had seen at least one specialist prior reported statistically significant higher scores in understanding their condition (Q3) (p = 0.01) and in understanding what to do next (Q6) (p = 0.028).

Overall patient satisfaction scores (Q14) did not correlate with patients' responses to individual treatment goal questions (Table 3). There were no trends among the five patients who had stated among their treatment goals to be 'pain free', with one patient giving high overall satisfaction scores including a '10' for overall satisfaction (Q14), two patients contacted by phone stating that they were satisfied overall, one unable to be contacted by mail or phone, and one who gave consistently low scores in the questionnaire including the only '0' score for overall patient satisfaction (Q14) among all respondents.

Discussion

Among the few studies looking at patient satisfaction in the chronic facial pain population, satisfaction with care and treatment before referral to a specialist facial pain unit has been found to be only moderate at best, with the majority of patients being dissatisfied with their care after having seen multiple providers of different subspecialties.10,11 One study cited multiple instances of poor communication and understanding on the part of previous providers as the reason for patient dissatisfaction.10 In this audit, patients reported low scores for the management of their pain before their consultation visit (Q1), conceivably because they do not have the correct diagnosis of and treatment for their condition, knowledge about the condition and how to manage it, and resources to support them in their management (ie psychology and psychiatry). In our audit, there was a trend towards higher overall satisfaction (Q14) among patients who had seen more specialists, and those referred to the unit by providers other than general medical practitioners. Up to 46% of the sample had been referred by specialists, which bears out Charon's statement12 that pain clinics see patients when all other specialists have failed to provide support. She goes on to highlight the role of pain physicians as professionals who have learned to deal with defeat, but also who need '...to exude optimism and hope, recognise the patient's fear that there is nothing more to offer and must realistically hold out at least a promise of accompanying the patient along his or her road of pain. The goals of care in pain medicine are chosen jointly by patient and care giver.'

Overall satisfaction and reported ratings to other questions in this audit were not affected by demographics, diagnoses, treatment plan, or treatment goals. This is consistent with a similar study that reported high levels of patient satisfaction with initial consultation appointments, with favourable relationships between patients and providers.13 Within that study, there was some dissatisfaction with communications, diagnosis and treatment outcomes, which was also found to a smaller degree in our audit, however the dissatisfaction was more due to administrative and procedural reasons. Patient expectation of being 'cured of their condition', when in fact there is no such thing, may also play a part in their satisfaction ratings. However all patients are explicitly told that a cure is not possible and that all we can achieve is a reduction in pain as the pain is chronic in nature. It is heavily stressed that the pain is real and not due to mental health problems. Some patients for whom English was not their first language may have been confused by the questionnaire, as found in one who included 'being pain free' as a treatment goal, and gave consistently low scores for all questions, with an overall satisfaction score (Q14) of 0.

Overall satisfaction with the care received does not necessarily translate to satisfaction with the impact of their visit to their overall problem, which was not captured in this survey, as this audit concentrated more on the processes. The questionnaire used in this audit has not been psychometrically tested, although some of the questions were based on those published by the British Pain Society,9 and others were based on suggestions from institutes such as the Picker Institute, which designs patient satisfaction surveys throughout the UK. Responder bias may exist in this audit, with survey respondents having the highest satisfaction, telephone respondents having a lower satisfaction, and non-responders having the lowest satisfaction, with such data not being captured. Patients contacted by telephone may have not been entirely truthful about their views since no attempt was made to complete the questionnaire. In addition, all of the questions in the survey were 'positively worded' with affirmative statements, which may result in acquiescence bias due to respondents simply giving the same or similar responses to all questions. Furthermore, there is a suggestion that dissatisfaction is only expressed when extremely negative events occur, thereby producing bias and over-reporting of high satisfaction.14 Sending the questionnaire together with the letter detailing the consultation may be another source of bias; however this was done to save on the costs of postage.

Our regular assessment of treatment goals of our patients, a questionnaire used for over 10 years, suggested that patients wanted a better understanding of their pain and for all their concerns to be addressed. We had also developed patient information leaflets with the help of the local patient advisory group and wanted to ascertain whether these were useful. Letters sent to the patients and referring providers are comprehensive, and although addressed to healthcare practitioners, provide reminders to patients that there are things they need to be doing to take control of their pain condition. The letters do take time to write, and we wanted to gain feedback as to whether the time spent is worthwhile. Results for Q10 and Q11 highlight the importance of education and communication materials for both the patients and the providers, strengthening communications to providers and patients, and allowing both to take an active role in the management of the condition. These factors are consistent with findings in medical outpatients that providers' attitudes and high attention towards pain, and provision of good information to the patient about their condition and related matters is equally, or even more important than the actual treatment.15,16,17

The lowest mean score among all satisfaction questions was for the few respondents (n = 8) who rated the outcome of care received from other providers within the same hospital, from other subspecialties and/or disciplines both within and outside the facial pain unit team. This may be attributed to patients' preference for continuity of provision of care by a single provider, predisposition towards being unsatisfied due to previous lack of success with other providers, or because they had yet to be seen by the other providers.

The high scores for Q2, Q3, Q4, Q5, Q6 and Q9 highlight most importantly, the need for extended appointment times at the consultation visit in order to accomplish the objective of sufficient patient understanding about their condition. Such outcomes can only be accomplished by allowing the provision of adequate time per appointment to provide a plausible diagnosis, explanation, and support with hope.

The representative sample of this unit's patient population cannot necessarily be applicable to the overall population of chronic facial pain patients, as further studies with larger numbers of patients are required. In addition, there remains an opportunity to look at patient satisfaction longitudinally at points after the initial visit, after they are well into their treatment and management plan. Parameters that may be evaluated include the relationship between satisfaction with pain treatment effectiveness and subsequent utilisation of healthcare resources due to their condition.

Conclusions

For complex chronic facial pain patients, patient centred care that is delivered in a comprehensive consultation visit, which addresses their goals, provides explanation and education about their condition and its management, and provides the necessary resources in doing so, leads to high overall patient satisfaction. The provision of adequate time per patient visit (ie 45 minutes to 1 hour), with comprehensive summary letters is essential and should result in decreased utilisation of time and healthcare resources and favourable patient outcomes.

References

Cairns C B, Garrison H G, Hedges J R, Schringer D L, Valenzuela T D . Development of new methods to assess the outcomes of emergency care. Acad Emerg Med 1998; 5: 157–161.

Ware J, Snyder M, Wright R, Davies A . Defining and measuring patients' satisfaction with medical care. Eval Program Plann 1983; 6: 247–263.

Sitzia J, Wood N . Patient satisfaction: a review of issues and concepts. Soc Sci Med 1997; 45: 1829–1843.

Department of Health. Essence of care 2010. Benchmarks for the prevention and management of pain. UK: Department of Health, 2010.

American Pain Society Quality of Care Committee. Quality improvement guidelines for the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain. JAMA 1995; 274: 1874–1880.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Acute pain management in adults: operative procedures. (AHCPR publication no. 92–0019). Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1992.

Ward S E, Gordon D B . Patient satisfaction and pain severity as outcomes in pain management: a longitudinal view of one setting's experience. J Pain Symptom Manage 1996; 11: 242–251.

The Royal College of Anaesthetists and The Pain Society. Pain management services good practice, May 2003. London: The Royal College of Anaesthetists and The Pain Society, 2003.

British Pain Society and the Royal College of General Practitioners. A practical guide to the provision of chronic pain services for adults in primary care. UK: British Pain Society and the Royal College of General Practitioners, 2004.

Türp J C, Kowalski C J, Stohler C S . Treatment-seeking patterns of facial pain patients: many possibilities, limited satisfaction. J Orofac Pain 1998; 12: 61–66.

Wolf E, Birgerstam P, Nilner M, Petersson K . Patients' experiences of consultations for nonspecific chronic orofacial pain: a phenomonological study. J Orofac Pain 2005; 20: 226–233.

Charon R. A narrative medicine for pain. In Carr D B, Loeser J D, Morris DB (eds) Narrative pain and suffering. pp 29–44. Seattle: IASP Press, 2005.

Murray H, Locker D, Mock D, Tenenbaum H . Patient satisfaction with a consultation at a cranio-facial unit. Community Dent Health 1997; 142: 69–73.

Williams B, Coyle J, Healy D . The meaning of patient satisfaction: an explanation of high reported levels. Soc Sci Med 1998; 47: 1351–1359.

McNeil J A, Sherwood G D, Starck P L, Thompson C J . Assessing clinical outcomes: patient satisfaction with pain management. J Pain Symptom Manage 1998; 16: 29–40.

Ward S E, Gordon D . Application of the American Pain Society quality assurance standards. Pain 1994; 56: 299–306.

Perrion N J, Bovier P . Pain management in a medical walk-in clinic: link between recommended processes and pain relief. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 19: 274–280.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank William VanDeByl for his help in setting up the audit, and the secretaries in the facial pain unit for helping in collecting the data. Professor Zakrzewska undertook this work at University College London (UCL)/UCL Hospitals Trust, who received a proportion of funding from the Department of Health's National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre funding scheme. We are also grateful for the very comprehensive comments of one of the reviewers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Napeñas, J., Nussbaum, M., Eghtessad, M. et al. Patients' satisfaction after a comprehensive assessment for complex chronic facial pain at a specialised unit: results from a prospective audit. Br Dent J 211, E24 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.1054

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.1054

This article is cited by

-

Clinical presentations on a facial pain clinic

British Dental Journal (2020)

-

Accuracy of the painDETECT screening questionnaire for detection of neuropathic components in hospital-based patients with orofacial pain: a prospective cohort study

The Journal of Headache and Pain (2018)

-

Orofacial pain – an update on diagnosis and management

British Dental Journal (2017)