Abstract

Misuse of antibiotics by the medical profession is a global concern. Examining doctors’ knowledge about antimicrobials will be important in developing strategies to improve antibiotic use. The aim of the study was to survey Chinese doctors’ knowledge on antibiotics and reveal the factors associated with their level of knowledge. A cross-sectional survey was conducted in Shanxi in central China. A total of 761 physicians were surveyed using a structured self-administered questionnaire. A generalized linear regression model was used to identify the factors associated with doctors’ knowledge on antibiotic. Based on a full score of 10, the average score for doctors’ knowledge on antibiotics was 6.29 (SD = 1.79). Generalized linear regression analysis indicated that doctors who either worked in the internal medicine department, who were chief doctors or who received continuing education on antibiotic, had better knowledge of antibiotics. Compared with doctors working in tertiary hospitals, doctors working in secondary hospitals or primary healthcare facilities had poorer knowledge about antibiotics. Chinese doctors have suboptimal knowledge about antimicrobials. Ongoing education is effective to enhance doctors’ knowledge, but the effect remains to be further improved. More targeted interventions and education programs should improve knowledge about antimicrobials, especially for doctors working in primary healthcare institutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Resistance to antibiotics is a growing worldwide public health problem1,2,3,4, leading to a delay in the administration of effective therapy and increased hospital costs, morbidity and mortality5 The widespread inappropriate use of antibiotics is considered as one of the important significant causes of the development of microbial antibiotic resistance6,7,8,9. These facts have prompted many to call for improvements in the way doctors’ prescribe antimicrobials to patients10,11. The extent of the doctors’ knowledge on antibiotic use has been identified as a key factor that affects individual prescribing behavior12. Therefore, it is important to better understand the breadth of knowledge doctors have regarding antibiotic use.

Previous surveys have been conducted to assess doctors’ knowledge about antimicrobials in many countries13,14,15,16,17,18,19. As China is one such country with a history of serious abuse of antibiotic use20,21,22, and there has been very little research on doctors’ knowledge concerning antibiotic use in China, further research is urgently needed. Previous studies have mainly focused on descriptive analyses of doctors’ knowledge and have failed to identify the key factors that can be used to develop targeted and effective interventions13,14,15,19. The present study aims to measure doctors’ knowledge on antibiotic use in China and reveal these factors.

Result

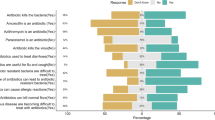

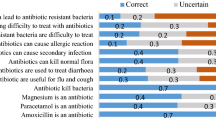

Table 1 presents study participant characteristics. A total of 761 participants comprising 473 female doctors (62.16%) and 288 male doctors (37.84%) were surveyed in this study. The mean age of participants was 35.55 years, with standard deviation (SD) of 8.49. Of the participants, more than half had achieved a bachelor degree or above, and their mean working duration in hospital was 10.75 years (SD = 9.45). Approximately 90% had received continuing education on antibiotics use. Based on a full score of 10, the average antibiotic knowledge score was 6.29 (SD = 1.79).

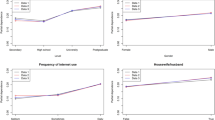

Table 2 presents factors associated with physician’s knowledge on antibiotics. There was no significant difference in the mean score according to age (P = 0.24), gender (P = 0.36), educational level (P = 0.38 for Bachelor degree and P = 0.58 for Master degree or higher), and working duration in hospitals (P = 0.55). Physicians who worked in the internal medicine department had higher mean knowledge scores than that of those who worked in the pediatrics department (P < 0.02), in the stomatology department (P < 0.01), and in the general practice department (P < 0.01). Chief doctors had a significantly higher mean knowledge score compared with doctors with junior title (P < 0.01). Doctors who worked in primary healthcare facilities (P < 0.01), as well as those who working in secondary hospitals (P < 0.01), had lower average scores than those that worked in tertiary hospital. Doctors receiving continuing education on antibiotics had a higher mean score than doctors who did not (P < 0.01).

Discussion

This study is the first in China to more comprehensively assess doctors’ knowledge on antibiotic use. Based on analysis of the doctors’ scores from the questionnaire survey, overall knowledge of antimicrobials was much lower than expected. As a benchmark, the mean antibiotic knowledge score in this study was similar to that reported by a previous study conducted in the Congo15, but was lower than the result from a comparable survey conducted in Peru14. The results from different countries may differ owing to the doctors’ level of education and the standard of care in the different tiered hospitals. For example in Congo and Peru, the study participants were doctors who worked in tertiary hospitals or in teaching hospitals14,15. In contrast, participants recruited in the present study were from high technical tertiary hospitals as well as relative low technical level hospitals.

Multivariable generalized linear regression modeling indicated that doctors who worked in tertiary hospitals had a significantly higher mean knowledge score compared with those who worked in primary healthcare facilities and secondary hospitals. This may be attributed to the fact that doctors in tertiary hospitals have many more opportunities for participation in research and national conferences. Nevertheless, the doctors’ knowledge on antibiotic use even in tertiary hospitals is still insufficient. In addition, the knowledge score on antibiotic use of doctors working in primary healthcare facilities was the lowest. As the primary healthcare facilities (community health centers and township hospitals) in China cover a large number of patients, we propose that doctors working in primary healthcare facilities should be selected as the key target group for training intervention.

Other studies have demonstrated that continuing education is an effective intervention to increase doctors’ knowledge on antibiotic use and to improve their prescribing behavior23,24,25. Our study showed that doctors who received training on antibiotic use in the past year had better antibiotic knowledge, consistent with the previous studies. It should be noted however, that even though more than ninety percent of doctors received training in the present study, they still had a suboptimal knowledge about antimicrobials. This indicates that more regular and improved training methods should be actively promoted. Therefore, it will be necessary to review the key factors that influence doctors’ learning on the use of antibiotics so that more effective educational programs can be developed and implemented.

The present study also demonstrated that doctors who worked in internal medicine department had a relatively better knowledge on antibiotics use, which may simply be due to the fact that they prescribe antibiotics more frequently and pay more careful attention to knowledge about antibiotic use13. Previous studies have indicated that consulting with senior physicians is an important knowledge source for junior physicians13,14. However, in this study the knowledge scores of assistant chief doctors and doctors in charge were not significantly increased relative to doctors with junior title, which needed more attention and further research.

The survey instrument used in this study for assessing knowledge of antibiotic use has been widely adopted in other countries13,14,15. Importantly, in this study, the questionnaire was distributed and completed on-site, precluding introduction of bias due to consultancy of peers or reference to published resources. Therefore, we believe that the results of the study reflect the true knowledge of the doctors’ surveyed. However, because our survey was conducted at only one city in China, the results must be generalized with caution.

Some research pointed out that lack of knowledge and training regarding antibiotics may attribute to the inappropriate use of antibiotics26,27. Recently a large-scale retrospective cohort study showed that physicians’ attitudes and knowledge determine the quality of prescription of antibiotics28. Therefore, understanding the doctors’ knowledge on antibiotic use and the associated factors is crucial to make better efforts to promote appropriate antibiotic prescribing. This study found that doctors have suboptimal knowledge about antimicrobials in China. Although ongoing education was partly effective in enhancing doctors’ knowledge on antibiotic use, the effect remains to be further improved. In addition, doctors coming from primary healthcare institutions had poorer knowledge on antibiotic use, which indicated that more targeted interventions and education programs are urgently needed in these hospitals.

Methods

Survey instrument

A self-administered questionnaire was used in the present study, which was developed according to a previous questionnaire used in the US, Peru, and Congo13,14,15, and further adapted to the setting in China. Prior to release, the questionnaire was reviewed by a team of five infectious diseases physicians to assess the relevance and wording of the questions as well as accuracy of the translation into Chinese. Then, the questionnaire was pilot-tested on 20 doctors to ensure that the questions were clear and understandable to all participants. The questionnaire was divided into three sections, namely; socio-demographic information, knowledge on antibiotic use and continuing education about antibiotics. Socio-demographic information included gender, age, educational level, specialty and working age. Doctors’ knowledge was assessed by ten antimicrobial questions about the clinical indications, spectrum, and pharmacology of antibiotics. In summary, three questions addressed the choice of antibiotics for treating acute diarrhea, upper respiratory tract infection and sepsis in a patient with impaired renal function; two questions addressed the safety of antibiotics for pregnant women and children; three questions addressed the spectrum of antibiotics and two questions addressed the pharmacology of antibiotics. Continuing education was also investigated by one question that addressed training in antibiotic use. “During the last year, did you receive any training on antibiotic use?”.

Sampling design and data collection

This is a cross-sectional study. Data were collected from October 2012 to October 2013 in the city of Taiyuan, Shanxi Province (Central China). There were ten tertiary hospitals, thirteen secondary hospitals and sixty-two primary healthcare facilities in Taiyuan in 2012. Tertiary hospitals are the highest level with the best medical equipment and technology, while primary healthcare facilities are the lowest level including community health centers and township hospitals. A stratified cluster random sampling method was employed in the present study. In the first stage, hospitals were divided into three groups according to their hierarchy level, and then two tertiary hospitals, two secondary hospital and twelve primary healthcare facilities were randomly sampled from each hospital group. In the second stage, all licensed medical doctors from general practice, internal medicine, surgery, gynecology and obstetrics, pediatrics and stomatology in the selected hospitals were invited to participate in the survey. Medical doctors from psychiatry, radiology, ophthalmology and anesthesiology were not included as they do not routinely prescribe antibiotics. Considering that doctors have holidays by turns, we went to each selected hospital several times to ensure that all licensed doctors from the above department had a chance to be invited to participate in survey to collect more representative data. Questionnaires were distributed on site during working time by postgraduate students. In order to accurately assess doctors’ knowledge on antibiotic use, participants were asked to respond immediately without referring to the literature or consulting others. Additionally, participants were asked to make a written commitment not to disclose the questions to their colleagues when they signed the written informed consent.

Statistical analysis

All statistical procedures were performed using the Statistical Analysis System

(SAS) 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Each antimicrobial question was given a score of one point if the doctor selected the correct answer, and a score of zero if the answer was incorrect. The cumulative score of the ten antimicrobial questions was then calculated to assess doctors’ knowledge on antibiotic use. Descriptive analyses included means for continuous variables and percentages for categorical data. A generalized linear regression model was used to examine the associations of independent variables with doctors’ antibiotic knowledge scores. All comparisons were two-tailed. The significance threshold was a P value of <0.05.

This study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China. Written informed consent was provided for each respondent, and the identifying details of all study subjects were kept confidential.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Bai, Y. et al. Factors associated with doctors' knowledge on antibiotic use in China. Sci. Rep. 6, 23429; doi: 10.1038/srep23429 (2016).

References

World Health Organization. The evolving threat of antimicrobiao resistance: options for action. (2012) Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44812/1/9789241503181_eng.pdf?ua=1. (Accessed: 10/12/2013).

Kumar, R., Indira, K., Rizvi, A., Rizvi, T. & Jeyaseelan, L. Antibiotic prescribing practices in primary and secondary health care facilities in Uttar Pradesh, India. Journal of clinical pharmacy and therapeutics. 33, 625–634 (2008).

Seppala, H. et al. The effect of changes in the consumption of macrolide antibiotics on erythromycin resistance in group A streptococci in Finland. Finnish Study Group for Antimicrobial Resistance. The New England journal of medicine. 337, 441–446 (1997).

van Bijnen, E. M. et al. The appropriateness of prescribing antibiotics in the community in Europe: study design. BMC infectious diseases. 11, 293 (2011).

Cosgrove, S. E. & Carmeli, Y. The impact of antimicrobial resistance on health and economic outcomes. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 36, 1433–1437 (2003).

Arason, V. A., Sigurdsson, J. A., Erlendsdottir, H., Gudmundsson, S. & Kristinsson, K. G. The role of antimicrobial use in the epidemiology of resistant pneumococci: A 10-year follow up. Microbial drug resistance (Larchmont, N.Y.). 12, 169–176 (2006).

Costelloe, C., Metcalfe, C., Lovering, A., Mant, D. & Hay, A. D. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 340, c2096 (2010).

Kahlmeter, G., Menday, P. & Cars, O. Non-hospital antimicrobial usage and resistance in community-acquired Escherichia coli urinary tract infection. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 52, 1005–1010 (2003).

Magee, J. T., Pritchard, E. L., Fitzgerald, K. A., Dunstan, F. D. & Howard, A. J. Antibiotic prescribing and antibiotic resistance in community practice: retrospective study, 1996–8. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 319, 1239–1240 (1999).

Goldmann, D. A. et al. Strategies to Prevent and Control the Emergence and Spread of Antimicrobial-Resistant Microorganisms in Hospitals. A challenge to hospital leadership. Jama. 275, 234–240 (1996).

Jarvis, W. R. Preventing the emergence of multidrug-resistant microorganisms through antimicrobial use controls: the complexity of the problem. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. 17, 490–495 (1996).

Hulscher, M. E., Grol, R. P. & van der Meer, J. W. Antibiotic prescribing in hospitals: a social and behavioural scientific approach. The Lancet. Infectious diseases. 10, 167–175 (2010).

Srinivasan, A. et al. A survey of knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of house staff physicians from various specialties concerning antimicrobial use and resistance. Archives of internal medicine. 164, 1451–1456 (2004).

Garcia, C. et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practice survey about antimicrobial resistance and prescribing among physicians in a hospital setting in Lima, Peru. BMC clinical pharmacology. 11, 18 (2011).

Thriemer, K. et al. Antibiotic prescribing in DR Congo: a knowledge, attitude and practice survey among medical doctors and students. PloS one. 8, e55495 (2013).

Dyar, O. J., Pulcini, C., Howard, P. & Nathwani, D. European medical students: a first multicentre study of knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of antibiotic prescribing and antibiotic resistance. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 69, 842–846 (2014).

Navarro-San Francisco, C. et al. Knowledge and perceptions of junior and senior Spanish resident doctors about antibiotic use and resistance: results of a multicenter survey. Enfermedades infecciosas y microbiologia clinica. 31, 199–204 (2013).

Pulcini, C., Williams, F., Molinari, N., Davey, P. & Nathwani, D. Junior doctors’ knowledge and perceptions of antibiotic resistance and prescribing: a survey in France and Scotland. Clinical microbiology and infection: the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 17, 80–87 (2011).

Quet, F. et al. Antibiotic prescription behaviours in Lao People’s Democratic Republic: a knowledge, attitude and practice survey. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 93, 219–227 (2015).

Dong, L., Yan, H. & Wang, D. Antibiotic prescribing patterns in village health clinics across 10 provinces of Western China. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 62, 410–415 (2008).

Li, Y. et al. Overprescribing in China, driven by financial incentives, results in very high use of antibiotics, injections, and corticosteroids. Health affairs (Project Hope). 31, 1075–1082 (2012).

Yin, X. et al. A systematic review of antibiotic utilization in China. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 68, 2445–2452 (2013).

Kiang, K. M. et al. Clinician knowledge and beliefs after statewide program to promote appropriate antimicrobial drug use. Emerging infectious diseases. 11, 904–911 (2005).

Akter, S. F., Heller, R. D., Smith, A. J. & Milly, A. F. Impact of a training intervention on use of antimicrobials in teaching hospitals. Journal of infection in developing countries. 3, 447–451 (2009).

Roque, F. et al. Educational interventions to improve prescription and dispensing of antibiotics: a systematic review. BMC public health. 14, 1276 (2014).

Srinivasan, A. et al. A survey of knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of house staff physicians from various specialties concerning antimicrobial use and resistance. Arch Intern Med. 164, 1451–1456 (2004).

Md Rezal, R. S. et al. Physicians’ knowledge, perceptions and behaviour towards antibiotic prescribing: a systematic review of the literature. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 13, 665–680 (2015).

Gonzalez-Gonzalez, C. et al. Effect of Physicians’ Attitudes and Knowledge on the Quality of Antibiotic Prescription: A Cohort Study. Plos One. 10, e0141820 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71403091). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors also thank all study participants who have been involved and contributed to the procedure of data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.B., S.W., Y.G. and X.Y. designed the study, Y.B., S.W. and J.B. participated in the acquisition of data, which were analyzed by Y.G. and X.Y., Y.B. and X.Y. drafted the manuscript and Y.G. and Z.L. revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Bai, Y., Wang, S., Yin, X. et al. Factors associated with doctors’ knowledge on antibiotic use in China. Sci Rep 6, 23429 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep23429

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep23429

This article is cited by

-

Urinary phthalate metabolites in pregnant women: occurrences, related factors, and association with maternal hormones

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2022)

-

Prevalence and risk factors for antibiotic utilization in Chinese children

BMC Pediatrics (2021)

-

Knowledge, attitudes and behaviors on antibiotic use and resistance among healthcare workers in Italy, 2019: investigation by a clustering method

Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control (2021)

-

Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding antibiotic use and resistance among medical students in Colombia: a cross-sectional descriptive study

BMC Public Health (2020)

-

Antibiotic prescribing in paediatric inpatients in Ghana: a multi-centre point prevalence survey

BMC Pediatrics (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.