Abstract

Background:

While treatment for breast cancer has been refined and overall survival has improved, there is concern that the incidence of brain metastases has increased.

Methods:

We identified patients in Sweden with incident breast cancer 1998–2006 in the National Cancer Register, and matched these to the National Patient Register to obtain information on hospital admissions for distant metastases. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed with Cox regression as estimates of relative risk.

Results:

Among 50 528 breast cancer patients, 696 (1.4%) were admitted with brain metastases during median 3.5 years of follow-up. Admissions for other metastases were found in 3470 (6.9%) patients. Compared with the period 1998–2000, patients diagnosed with breast cancer 2004–2006 were at a 44% increased risk of being admitted with brain metastases (HR 1.44, 95% CI 1.13–1.85).

Conclusion:

The incidence of admissions with brain metastases in breast cancer patients was increasing in the mid-2000s in Sweden. These findings support a true increase in incidence of brain metastases among breast cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The occurrence of brain metastases in breast cancer patients is believed to have increased (Lin and Winer, 2007), but available supportive evidence is scarce (Smedby et al, 2009). If so, this may be an effect of increased incidence of primary breast cancer (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2011b), technical advances in neuroimaging, or a true increase in incidence due to modifications of systemic treatment schedules (Barnholtz-Sloan et al, 2004; Gavrilovic and Posner, 2005) and improved survival. Adjuvant and systemic therapy with low penetrance through the blood–brain barrier, such as trastuzumab, may, while decreasing risk of distant metastases in general and prolonging overall survival, lead to an increase in risk of brain metastases in breast cancer patients (Tomasello et al, 2010).

We recently showed that the number of admissions to hospital of patients with brain metastases in general, and especially due to breast cancer, increased in Sweden from 1987 to 2006, but we could not account for a parallel increase in primary breast cancer incidence nor for temporal changes in admission practices (Smedby et al, 2009). In the present study, we used nationwide health-care registers to investigate time trends in incidence of admissions for brain metastases and other distant metastases among patients with breast cancer during the period 1998–2006, with uniform classification of admission records.

Materials and methods

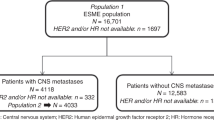

We identified 58 795 patients with breast cancer in the Swedish National Cancer Register (NCR) from 1 January 1998 to 31 December 2006. Previous cancer patients were excluded, leaving 50 528 patients in the cohort. The NCR is estimated to be >95% complete (Barlow et al, 2009). The cohort was then matched to the National Patient Register, NPR, (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2011a) by the national registration numbers assigned to all citizens, to obtain information on all hospital admissions for distant metastases during follow-up. The NPR contains individualised information on ICD diagnoses associated with all hospitalisations nationwide since 1987, with an estimated proportion of register drop-outs of <2%. TNM classification data from the primary breast cancer diagnosis were available from 2002 (no restrictions were made based on TNM stages). The cohort was also matched to the National Cause of Death Register (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2011c). The study was approved by the Stockholm Regional Research Ethics Board.

Statistical analyses

The number of incident cases of breast cancer and proportion admitted with brain metastases and/or other distant metastases are presented and compared per time periods 1998–2000, 2001–2003, and 2004–2006. Only the first admission with brain metastases or with metastases at any site outside of the brain (‘other distant metastases’) was considered. Patients recorded with brain metastases as the only metastatic site at their first admission were denoted as ‘First brain metastases’. For patients admitted with brain metastases at the same time, or subsequent to admissions for other distant metastases, we used the term ‘Later brain metastases’. We assessed the 1-, 2-, and 3-year cumulative incidence of brain metastases admissions by year of primary diagnosis, and the incidence was plotted graphically with the Kaplan–Meier method by 3-year calendar periods. We used a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for year of birth to compute hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) as a measure of the relative risk of admissions for distant metastases in the brain or other sites comparing 3-year periods. No direct statistical comparisons were made between risk of admissions for brain metastases and other distant metastases. All individuals were followed from the date of primary breast cancer to date of death, or 31 December 2006, whichever came first. The patients were censored if they contracted another cancer during this time.

Results

In the cohort of 50 528 patients with breast cancer, 696 (1.4%) were admitted with brain metastases during a median follow-up of 3.5 years (Table 1). Three-hundred and thirty-six (0.7%) patients were admitted with brain metastases as their first distant metastasis and the remaining 360 (0.7%) were admitted for brain metastases in parallel with or subsequent to metastases at other sites. Admissions with other distant metastases were found in 3470 (6.9%) patients. The majority of the patients (97%) diagnosed from 2002 and onwards did not have clinically evident systemic disease (M1) at diagnosis.

The median time between diagnosis and first admission for brain metastases was 2.3 (1.3–4.0) years and shorter for those with a first metastasis to the brain (1.8 years) than those who were admitted with brain metastases as part of a widespread disease (2.9 years) (Table 1). The prevalence of survivorship at the end of each 3-year period of primary diagnoses increased marginally from 93.0% 1998–2000 (n=15 038) to 93.9% 2001–2003 (n=16 060) and 93.8% 2004–2006 (n=16 184). Survival among patients admitted with brain metastases was median 3.1 years from primary breast cancer diagnosis, and 3 months from the day of first admission for brain metastasis (Table 1).

The incidence of admissions with brain metastasis during the first year after breast cancer diagnosis varied from 1.1 to 3.1 per 1000 person-years, from 2.7 to 4.4 per 1000 person-years during the first 2 years of follow-up, and from 2.7 to 4.2 per 1000 person-years (Supplementary Table 1). Rates were lowest in 1999 and increased through 2004–2005. Compared with the period 1998–2000, patients diagnosed with a primary breast cancer during 2001–2003 were at 17% increased risk of being admitted with brain metastases (HR 1.17, 95% CI 0.99–1.39) during follow-up, and patients diagnosed 2004–2006 were at a 44% increased risk (HR 1.44, 95% CI 1.13–1.85) (Figure 1). The risk was more pronounced for later brain metastases (HR 1.80, 95% CI 1.23–2.63) than for first brain metastases (HR 1.21, 95% CI 0.87–1.68) in 2004–2006, compared with the period 1998–2000. The relative risk of admissions with other distant metastases was 1.02 (95% CI 0.95–1.11) 2001–2003 and 1.11 (95% CI 1.00–1.24) 2004–2006, compared with the period 1998–2000. When assessing the risk of brain metastases by time of follow-up, the increased risk was primarily observed 1.5 years and onwards after primary breast cancer diagnosis 2004–2006 (HR 2.07, 95% CI 1.45–2.94) than during the first 1.5 years (HR 1.08, 95% CI 1.76–1.54), compared with the period 1998–2000 (Figure 1).

Discussion

In this large population-based register study of patients with incident breast cancer, we observed a 44% increase in risk of being admitted with brain metastases among patients diagnosed 2004–2006 compared with the period 1998–2000. Risk of admissions for other distant metastases did not increase to the same extent. Our findings further indicated that the rise in incidence of brain metastases primarily occurred among patients with widespread metastatic disease, and at least 1.5 years after the primary breast cancer diagnosis. Although the study is limited to admissions with brain metastases, our findings support a true increase in incidence of brain metastases during this time.

Two previous studies found no evidence for an increase in the incidence of brain metastases in breast cancer (Schouten et al, 2002) or in patients treated with trastuzumab (Lai et al, 2004). However, both studies spanned earlier time periods. In a more recent study, Pelletier et al (2008) observed an increase in incidence of brain metastases in breast cancer patients from 6.61% in 2002 to 10.92% in 2004. The cumulative incidence of brain metastases admissions in our cohort was 1.4%, which is a low incidence estimate compared with previous studies (Schouten et al, 2002; Barnholtz-Sloan et al, 2004; Gavrilovic and Posner, 2005; Tomasello et al, 2010). Our estimate based on hospital admissions is however bound to primarily represent individuals with severe symptoms requiring inpatient care rather than patients with subclinical disease. Also, median follow-up was shorter in our study than in other studies (Schouten et al, 2002; Barnholtz-Sloan et al, 2004). The patients who developed brain metastases were younger at primary breast cancer diagnosis than in the cohort overall, corresponding with the findings of others (Lin and Winer, 2007; Tomasello et al, 2010). The median survival from first admission with brain metastases was only a few months, also in line with other studies (Lin and Winer, 2007; Tomasello et al, 2010).

Breast cancer characteristics associated with more aggressive disease, ER and PR negativity and HER-2 overexpressing tumours (Gutierrez and Schiff, 2011; Stuckey, 2011) have been associated with an increased risk of brain metastases (Lin and Winer, 2007; Tomasello et al, 2010). Adjuvant anti-HER-2 antibody treatment, trastuzumab was introduced in 2000 and was gradually adopted in Sweden. It has been suggested that the introduction of trastuzumab may have altered the natural history of patients with HER-2-positive tumours and unmasked the CNS as a potential tumour cell sanctuary (Lin and Winer, 2007). Alternatively, an increase in incidence of brain metastases may be the result of more efficient palliative treatment and an improved survival among patients with metastatic disease. In a recent Swedish regional study, Foukakis et al (2011) reported an improved survival among patients with metastatic disease 60 years or younger for the period 2000–2004, but not among older patients.

The present population-based register study features near complete coverage of primary breast cancer patients and hospitalisations in Sweden and virtually no loss to follow-up. We cannot exclude that our findings are due to more frequent use of advanced radiological techniques such as CT and MR, which may lead to the detection of more cases of brain metastases. However, in our previous study of brain metastases among all cancer patients, admissions did not occur more frequently over time among patients with cancer types other than in the breast and lung (Smedby et al, 2009). Temporal changes in how we register disease at admission could also have influenced our results. However, risk of admissions for other distant metastases did not increase to the same extent in the present study. In addition, the number of hospital beds has decreased in Sweden during the last decade (OECD Health Data, 2005). Hence, the observed increasing trend cannot be due to facilitation of hospital admissions over time. A limitation of our study was the inability to account for stage at primary breast cancer diagnosis. However, since population screening with mammography has resulted in a relative increase of patients diagnosed with early stage breast cancer (Shen et al, 2011), our results cannot feasibly be ascribed to an increased incidence of breast cancer patients with stage IV.

To conclude, we found that the incidence of admissions with brain metastases among patients with breast cancer has increased over time in Sweden. If this also holds true for incidence of brain metastases per se needs to be confirmed in other population-based investigations with direct ascertainment of recurrence in the brain, and with access to more detailed data on breast cancer characteristics.

Change history

23 January 2013

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Barlow L, Westergren K, Holmberg L, Talback M (2009) The completeness of the Swedish Cancer Register: a sample survey for year 1998. Acta Oncol 48(1): 27–33

Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Sloan AE, Davis FG, Vigneau FD, Lai P, Sawaya RE (2004) Incidence proportions of brain metastases in patients diagnosed (1973 to 2001) in the Metropolitan Detroit Cancer Surveillance System. J Clin Oncol 22(14): 2865–2872

Foukakis T, Fornander T, Lekberg T, Hellborg H, Adolfsson J, Bergh J (2011) Age-specific trends of survival in metastatic breast cancer: 26 years longitudinal data from a population-based cancer registry in Stockholm, Sweden. Breast Cancer Res Treat 130(2): 553–560

Gavrilovic IT, Posner JB (2005) Brain metastases: epidemiology and pathophysiology. J Neurooncol 75(1): 5–14

Gutierrez C, Schiff R (2011) HER2: biology, detection, and clinical implications. Arch Pathol Lab Med 135(1): 55–62

Lai R, Dang CT, Malkin MG, Abrey LE (2004) The risk of central nervous system metastases after trastuzumab therapy in patients with breast carcinoma. Cancer 101(4): 810–816

Lin NU, Winer EP (2007) Brain metastases: the HER2 paradigm. Clin Cancer Res 13(6): 1648–1655

National Board of Health and Welfare (2011a) National Patient Register. Available at http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/register/halsodataregister/patientregistret/inenglish (accessed on 8 December 2011)

National Board of Health and Welfare (2011b) Cancer Incidence in Sweden 2009. Available at http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2010/2010-12-17 (accessed on 8 December 2011)

National Board of Health and Welfare (2011c) National Cause of Death Register. Available at http://socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2010/2010-4-33 (accessed on 8 December 2011)

OECD Health Data (2005) Available at http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/15/25/34970222.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2011)

Pelletier EM, Shim B, Goodman S, Amonkar MM (2008) Epidemiology and economic burden of brain metastases among patients with primary breast cancer: results from a US claims data analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 108(2): 297–305

Schouten LJ, Rutten J, Huveneers HA, Twijnstra A (2002) Incidence of brain metastases in a cohort of patients with carcinoma of the breast, colon, kidney, and lung and melanoma. Cancer 94(10): 2698–2705

Shen N, Hammonds LS, Madsen D, Dale P (2011) Mammography in 40-year-old women: what difference does it make? The potential impact of the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) Mammography Guidelines. Ann Surg Oncol 18(11): 3066–3071

Smedby KE, Brandt L, Backlund ML, Blomqvist P (2009) Brain metastases admissions in Sweden between 1987 and 2006. Br J Cancer 101(11): 1919–1924

Stuckey A (2011) Breast cancer: epidemiology and risk factors. Clin Obstet Gynecol 54(1): 96–102

Tomasello G, Bedard PL, de Azambuja E, Lossignol D, Devriendt D, Piccart-Gebhart MJ (2010) Brain metastases in HER2-positive breast cancer: the evolving role of lapatinib. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 75(2): 110–121

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Frisk, G., Svensson, T., Bäcklund, L. et al. Incidence and time trends of brain metastases admissions among breast cancer patients in Sweden. Br J Cancer 106, 1850–1853 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.163

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.163

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Adding simultaneous integrated boost to whole brain radiation therapy improved intracranial tumour control and minimize radiation-induced brain injury risk for the treatment of brain metastases

BMC Cancer (2023)

-

An electrostatically conjugated-functional MNK1 aptamer reverts the intrinsic antitumor effect of polyethyleneimine-coated iron oxide nanoparticles in vivo in a human triple-negative cancer xenograft

Cancer Nanotechnology (2023)

-

Liquid biopsy for brain metastases and leptomeningeal disease in patients with breast cancer

npj Breast Cancer (2023)

-

Development and external validation of a prediction model for brain metastases in patients with metastatic breast cancer

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2023)

-

Brain radiotherapy, tremelimumab-mediated CTLA-4-directed blockade +/− trastuzumab in patients with breast cancer brain metastases

npj Breast Cancer (2022)