Abstract

Background:

Data regarding the safety and effectiveness of aromatase inhibitors (AIs) as monotherapy or combined with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue in male breast cancer are scarce.

Methods:

In this retrospective chart review, cases of male breast cancer patients treated with AIs with or without a GnRH analogue were evaluated.

Results:

Twenty-three men were included into this case series. Aromatase inhibitors in combination with or without a GnRH analogue were given as first-line therapy in 60.9% and as second-line therapy in 39.1% of patients, respectively. All patients had visceral metastases, whereas in five of them bone lesions coexisted. In all cases AIs were tolerated well, and no case of grade 3 and 4 adverse events was reported. A partial response was observed in 26.1% of patients and stable disease in 56.5%. Median overall survival (OS) was 39 months and median progression-free survival (PFS) was 13 months. Regarding OS and PFS, no significant effects of GnRH analogue co-administration or type of AI were noted.

Conclusion:

Our study shows that AIs with or without GnRH analogues may represent an effective and safe treatment option for hormone-receptor positive, pretreated, metastatic, male breast cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Male breast cancer is an uncommon malignancy, accounting approximately for only 1% of all breast cancer cases (NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, 2012). The rarity of this disease has resulted in a limited amount of clinical data; indeed, very few clinical trials were conducted specifically in male patients and, conclusions concerning treatment strategies therefore have been generally drawn from trials conducted in female patients. Consequently, men with breast cancer are treated similarly to women, except for hormonal treatment (NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, 2012). More specifically, tamoxifen is still the golden standard of adjuvant endocrine treatment in male breast cancer and has a key role in the metastatic setting as well (NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, 2012; Eggemann et al, 2013).

Unlike tamoxifen, which acts as elective oestrogen receptor modulator, aromatase inhibitors (AIs) prevent the conversion of androstendione to 17β-estradiol (Jordan et al, 2011) Data from large randomised clinical trials in women have demonstrated a reduced risk of breast cancer recurrence with 5 years of adjuvant AIs as compared with 5 years of tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment (Bonneterre et al, 2000; Nabholtz et al, 2000; Mouridsen et al, 2001; Cuzick et al, 2010; Regan et al, 2011; Bliss et al, 2012). Hence, AIs are currently considered the treatment of choice for postmenopausal women with hormone-receptor (HR) positive breast cancer (Aebi et al, 2011; NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, 2012); their role in male breast cancer, however, remains elusive.

In preclinical models, administration of AIs was associated with significant increases in the respective levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and testosterone, whereas and no change in oestradiol (E2) levels was observed (Turner et al, 2000; Bighin et al, 2010). In healthy men, on the other hand, the administration of AIs caused a significant decrease in E2 levels; at the same time, an increase in levels of FSH, luteinising hormone, and testosterone was observed (Mauras et al, 2000; Bighin et al, 2010). Notably, the increase in testosterone levels may overcome the effect of aromatase inhibition by flooding the enzyme pathway with substrate, eventually resulting in only modest reduction of serum oestrogen levels and thereby limiting the clinical activity of AIs in men (White et al, 2011; Eggemann et al, 2013). Combination therapy with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues, that is, goserelin acetate effectively reduces the excess substrate levels, and may therefore maximise the effect of aromatase inhibition, suggesting that such a combination may be more effective than AIs alone in metastatic male breast cancer patients (Giordano and Hortobagyi, 2006; Soon Wong et al, 2007; Onami et al, 2010).

Data regarding the safety and effectiveness of AIs as monotherapy or combined with GnRH analogues in metastatic male breast cancer are scarce. Our retrospective study, the largest henceforth, therefore evaluated efficacy and safety of AIs with or without goserelin in metastatic male breast cancer cases.

Materials and methods

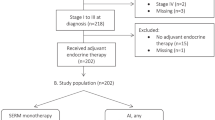

The study population was based on male patients with metastatic breast cancer who have been treated with AIs with or without a GnRH analogue. Eligible patients were selected from the Comprehensive Cancer Center of Vienna, Department of Medicine I/Division of Oncology, Vienna, Austria, from the 1st Propaedeutic Surgical Department of Hippocrateio Hospital, University of Athens, Athens, Greece and from the Department of Clinical Therapeutics, Alexandra Hospital, University of Athens, Greece. Patients were managed by dedicated teams of breast cancer specialists at these academic breast centres. The decision for further endocrine treatment after standard therapy with tamoxifen was taken in an interdisciplinary tumour board. Of note, the use of AI with or without a GnRH analogue, in each patient, was a medical decision taken independently of the presence of symptoms, visceral metastases or other clinical parameters. Patients’ medical records were reviewed and information regarding demography, pathology, and outcome was obtained; data of all patients were entered prospectively into the respective institutional clinical databases.

In all cases, an oral AI (either exemestane 25 mg, or letrozole 2.5 mg or anastrozole 1 mg) was administered daily, either alone or combined with a GnRH analogue (goserelin acetate 3.6 mg on day 1 in four weekly intervals). Treatment was continued until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Exclusion criteria were the following: (i) patients who had received AIs in the adjuvant setting, (ii) patients with HER2-positive breast tumours, (iii) patients who received concomitant chemotherapy, trastuzumab and/or radiotherapy (iv) previous GnRH analogue administration, (v) patients without at least one measurable or assessable non-measurable lesion and (vi) oestrogen receptor (ER)- and progesterone receptor (PgR)-negative primary and/or metastatic breast cancer.

In cases where more than one agent of the class of AI was administered consecutively, data regarding the first AI was included into the analysis. In patients with measurable disease, response was determined by RECIST 1.1 criteria. Fisher’s exact test was performed to assess whether co-administration of goserelin, as well as the type of administered AI (that is, irreversible steroidal inhibitor (exemestane) or a non-steroidal inhibitor (anastrozole and letrozole)), were associated with response rates.

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the interval between initiation of AI therapy and time of death, whereas progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the interval between initiation of AI therapy and time of progression or death of any cause. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were estimated for the graphical presentation of results. Log-rank test for the equality of survivor functions was performed in order to assess whether co-administration of goserelin as well as the type of administered AI was associated with differences in terms of OS and PFS.

Statistical analysis was performed with STATA 11.1 software (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). Written informed consent was obtained by all subjects participating in the study. The study is in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and has been approved by the local institutional review boards.

Results

Twenty-three men aged 53–76 years (64.4±6.5; mean±s.d.) were included into this case series. Patients’ characteristics are depicted in Table 1. All of them had undergone modified radical mastectomy. Eighteen of them (78.3%) were diagnosed with invasive ductal carcinoma, whereas the remaining five (21.7%) had infiltrative lobular carcinoma. The majority of patients presented with high grade neoplasms (grade 3: 47.8%; grade 2: 43.5%; grade 1: 8.7%). The ER Allred score varied between 4 and 8; the mean score was 6.61±1.20. The Allred score for PR varied between 0 and 7; the mean score was 4.91±1.81; all patients were HER2 negative, whereas ki-67 positivity (%) ranged between 10–60% (mean 31.0±13.8%). None of the patients included into this analysis was diagnosed with metastatic disease at first presentation.

The majority of patients received letrozole or anastrozole (82.6%); the remainders were treated with exemestane (17.4%). All patients except for one had received radiotherapy as part of their adjuvant treatment; the predominant adjuvant chemotherapy regimen was a combination of anthracyclins and taxanes (56.5%).

Adjuvant hormonal treatment was administered in 92.9% of cases; one patient did not consent. Of note, all patients had received tamoxifen beforehand. Aromatase inhibitors were given as monotherapy in 26.1% of patients, whereas in combination with goserelin acetate in 73.9% of patients. Aromatase inhibitors in combination with or without goserelin acetate were given as first-line therapy in 14 (60.9%) patients and as second-line therapy in nine (39.1%) patients. All patients had visceral metastases, whereas in five of them bone lesions coexisted. In all cases, AI with or without goserelin acetate was tolerated well, without grade 3 and 4 adverse events being reported.

Regarding best response, partial response (PR) was noted in 6 (26.1%) patients, stable disease (SD) in 13 (56.5%) patients, whereas progressive disease (PD) was observed in 4 (17.4%) patients. The GnRH analogue co-administration was not associated with response rates, as the PD : SD : PR ratio among patients receiving GnRH analogue and those who did not was 17.7% : 64.7% : 17.7% and 16.7% : 33.3% : 50.0%, respectively, (P=0.306, Fisher’s exact test). Similarly, steroidal inhibitor administration was not associated with response rates, as the PD : SD : PR ratio among patients receiving irreversible steroidal and non-steroidal inhibitors was 25.0% : 75.0% : 0.0% and 15.8% : 52.6% : 31.6%, respectively, (P=0.463, Fisher’s exact test).

Median OS was 39 months and median PFS was 13 months; corresponding Kaplan–Meier survival estimates are presented in Figures 1A and B, respectively. Regarding OS, no significant effects of goserelin co-administration (log-rank χ2(1)=0.38, P=0.536) or type of AI agent (log-rank χ2(1)=1.03, P=0.310) were noted. Similarly, goserelin co-administration (log-rank χ2(1)=0.04, P=0.850) and type of AI (log-rank χ2(1)=0.02, P=0.875) were not associated with PFS.

Discussion

Our study shows that AIs with or without GnRH analogues may represent an effective and safe treatment option for HR-positive, pretreated, metastatic, male breast cancer patients. It is possible that the high rate of responses achieved in our patient population may be attributed to the combination of AI with GnRH analogue. Moreover, the combination of an AI with a GnRH analogue in theory offers the added advantage of inhibiting the aromatisation of androgens to estrogens, while inhibiting the positive feedback loop to the hypothalamus/pituitary glands by the effect of goserelin acetate. This effect is of great importance taking into consideration that hormonal therapy is the mainstay of treatment in metastatic male breast cancer as men have a high rate of HR positivity, and thus excellent response rates to hormonal manipulation (Stalsberg et al, 1993; Rayson et al, 1998; Onami et al, 2010); nevertheless, the small sample size did not allow for the robust testing of such a hypothesis, and thus larger studies are needed in order to fully elucidate the role of goserelin in male breast cancer.

In male breast cancer, surgical hormonal ablative procedures were attempted initially, and in 1941, Farrow and Adair (1942) reported on the efficacy of orchiectomy. Other ablative techniques such as adrenalectomy and hypophysectomy were explored as well, with overall response rates of >50%. However, these techniques are now rarely used and have been substituted by medical hormonal treatment. Agents such as androgens, antiandrogens, steroids, estrogens, progestins and tamoxifen have shown promising activity, and are psychologically more acceptable to the majority of men than orchiectomy (Giordano et al, 2002; Arriola et al, 2007; White et al, 2011). Currently, tamoxifen is the cornerstone of hormonal treatment for male breast cancer, although the definition of this standard results from relatively small retrospective studies or is extrapolated from trials conducting in female breast cancer patients (Kantarjian et al, 1983; White et al, 2011). The use of fulvestrant in male breast cancer was proposed owing to their success in females, with a few published case series showing promising results in men as well (de la Haba Rodríguez et al, 2009; Masci et al, 2011; Zagouri et al, 2013).

The use of AIs in male breast cancer is well tolerated (Visram et al, 2010), but remains controversial. Initial case series have disappointingly shown negative or equivocal results; in a series of five patients, no objective response to anastrozole was observed (Giordano et al, 2002). Interestingly, however, there have been three individual cases of response to letrozole (Italiano et al, 2004; Zabolotny et al, 2005; Arriola et al, 2007), while Doyen et al (2010) reported promising results (CR: 13%; PR: 27% and SD: 13%), indicating relevant clinical activity of AIs in male breast cancer patients. In this study, median PFS and OS were 4.4 months (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.1–8.6) and 33 months (95% CI 18.4–47.6), respectively, (Doyen et al, 2010). In addition, the activity of letrozole was correlated with a significant reduction in E(-2-) levels, while secondary resistance was in part related to a deleterious feedback loop resulting in a significant upregulation of testosterone, thereby increasing substrate levels for aromatisation (Doyen et al, 2010). Hence, it was speculated that the combination of an AI with a GnRH analogue provide superior results.

Our study confirms that AIs combined with a GnRH analogue are active in male breast cancer, with a clinical benefit rate (CR, PR and s.d.⩾6 months) reported equal to 82.3%. Our observation is in accordance with data published in female breast cancer patients receiving AIs in metastatic setting (ORR ranging from 49% to 59%; time to treatment progression ranging from 8.3 to 11.1 months; Bonneterre et al, 2000; Nabholtz et al, 2000; Mouridsen et al, 2001). Moreover, our data are in accordance with the data published by (Giordano and Hortobagyi, 2006), on two male breast cancer patients treated with leuprolide acetate plus AIs. Still, results of patients receiving the combination of AIs and GnRH analogues were not significantly superior as compared with patients receiving AIs alone in our study. Therefore, it is obvious that no firm conclusion can be drawn, given the limited patient number as well as the limited amount of available literature. In addition, the main limitation of our study is its retrospective design; unfortunately, the SWOG-S0511 trial –a small, phase II trial in male breast cancer patients with recurrent or metastatic disease, in which goserelin was administered combined with anastrozole (ClinicalTrials.gov; ID: NCT00217659)– was closed prematurely owing to poor accrual (Sousa et al, 2013). Moreover, a randomised trial evaluating AIs in metastatic male breast cancer with or without a GnRH analogue is more than warranted.

Despite the limitations of a retrospective analysis, our results demonstrate that AIs in combination with or without goserelin may represent an effective and safe treatment option for HR-positive, pretreated, metastatic, male breast cancer patients who had progressed on tamoxifen. Further trials and large case series focused on male breast cancer and AI with or without goserelin seem mandatory to draw any firm conclusion.

Change history

11 June 2013

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Aebi S, Davidson T, Gruber G, Cardoso F ESMO Guidelines Working Group (2011) Primary breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 22: vi12–vi24.

Arriola E, Hui E, Dowsett M, Smith IE (2007) Aromatase inhibitors and male breast cancer. Clin Transl Oncol 9: 192–194.

Bighin C, Lunardi G, Del Mastro L, Marroni P, Taveggia P, Levaggi A, Giraudi S, Pronzato P (2010) Estrone sulphate, FSH, and testosterone levels in two male breast cancer patients treated with aromatase inhibitors. Oncologist 15: 1270–1272.

Bliss JM, Kilburn LS, Coleman RE, Forbes JF, Coates AS, Jones SE, Jassem J, Delozier T, Andersen J, Paridaens R, van de Velde CJ, Lønning PE, Morden J, Reise J, Cisar L, Menschik T, Coombes RC (2012) Disease-related outcomes with long-term follow-up: an updated analysis of the intergroup exemestane study. J Clin Oncol 30: 709–717.

Bonneterre J, Thürlimann B, Robertson JF, Krzakowski M, Mauriac L, Koralewski P, Vergote I, Webster A, Steinberg M, von Euler M . Anastrozole versus tamoxifen as first-line therapy for advanced breast cancer in 668 postmenopausal women: results of the Tamoxifen or Arimidex Randomized Group Efficacy and Tolerability study (2000) J Clin Oncol 18: 3748–3757.

Cuzick J, Sestak I, Baum M, Buzdar A, Howell A, Dowsett M, Forbes JF ATAC/LATTE investigators (2010) Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 10-year analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol 11: 1135–1141.

de la Haba Rodríguez JR, Porras Quintela I, Pulido Cortijo G, Berciano Guerrero M, Aranda E (2009) Fulvestrant in advanced male breast cancer. Ann Oncol 20: 1896–1897.

Doyen J, Italiano A, Largillier R, Ferrero JM, Fontana X, Thyss A (2010) Aromatase inhibition in male breast cancer patients: biological and clinical implications. Ann Oncol 21: 1243–1245.

Eggemann H, Ignatov A, Smith BJ, Altmann U, von Minckwitz G, Röhl FW, Jahn M, Costa SD (2013) Adjuvant therapy with tamoxifen compared to aromatase inhibitors for 257 male breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 137: 465–470.

Farrow JH, Adair FE (1942) Effect of orchidectomy on skeletal metastases from cancer of the male breast. Science 95: 654.

Giordano SH, Valero V, Buzdar AU, Hortobagyi GN (2002) Efficacy of anastrozole in male breast cancer. Am J Clin Oncol 25: 235–237.

Giordano SH, Hortobagyi GN (2006) Leuprolide acetate plus aromatase inhibition for male breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 24: e42–e43.

Italiano A, Largillier R, Marcy PY, Foa C, Ferrero JM, Hartmann MT, Namer M (2004) Complete remission obtained with letrozole in a man with metastatic breast cancer. Rev Med Interne 25: 323–324.

Jordan VC, Obiorah I, Fan P, Kim HR, Ariazi E, Cunliffe H, Brauch H (2011) The St. Gallen Prize Lecture 2011: evolution of long-term adjuvant anti-hormone therapy: consequences and opportunities. Breast 20: S1–11.

Kantarjian H, Yap HY, Hortobagyi G, Buzdar A, Blumenschein G (1983) Hormonal therapy for metastatic male breast cancer. Arch Intern Med 143: 237–240.

Masci G, Gandini C, Zuradelli M, Pedrazzoli P, Torrisi R, Lutman FR, Santoro A (2011) Fulvestrant for advanced male breast cancer patients: a case series. Ann Oncol 22: 985.

Mauras N, O'Brien KO, Klein KO, Hayes V (2000) Estrogen suppression in males: metabolic effects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85: 2370–2377.

Mouridsen H, Gershanovich M, Sun Y, Pérez-Carrión R, Boni C, Monnier A, Apffelstaedt J, Smith R, Sleeboom HP, Jänicke F, Pluzanska A, Dank M, Becquart D, Bapsy PP, Salminen E, Snyder R, Lassus M, Verbeek JA, Staffler B, Chaudri-Ross HA, Dugan M (2001) Superior efficacy of letrozole versus tamoxifen as first-line therapy for postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer: results of a phase III study of the International Letrozole Breast Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol 19: 2596–2606.

Nabholtz JM, Buzdar A, Pollak M, Harwin W, Burton G, Mangalik A, Steinberg M, Webster A, von Euler M (2000) Anastrozole is superior to tamoxifen as first-line therapy for advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women: results of a North American multicenter randomized trial. Arimidex Study Group. J Clin Oncol 18: 3758–3767.

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (2012) Breast Cancer. Version 2. (Available at http://www.nccn.com).

Onami S, Ozaki M, Mortimer JE, Pal SK (2010) Male breast cancer: an update in diagnosis, treatment and molecular profiling. Maturitas 65: 308–314.

Rayson D, Erlichman C, Suman VJ, Roche PC, Wold LE, Ingle JN, Donohue JH (1998) Molecular markers in male breast carcinoma. Cancer 83: 1947–1955.

Regan MM, Neven P, Giobbie-Hurder A, Goldhirsch A, Ejlertsen B, Mauriac L, Forbes JF, Smith I, Láng I, Wardley A, Rabaglio M, Price KN, Gelber RD, Coates AS, Thürlimann B BIG 1-98 Collaborative Group International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG) (2011) Assessment of letrozole and tamoxifen alone and in sequence for postmenopausal women with steroid hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: the BIG 1-98 randomised clinical trial at 8·1 years median follow-up. Lancet Oncol 12: 1101–1108.

Soon Wong N, Seong Ooi W, Pritchard KI (2007) Role of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog in the management of male metastatic breast cancer is uncertain. J Clin Oncol 25: 3787.

Sousa B, Moser E, Cardoso F (2013) An update on male breast cancer and future directions for research and treatment. Eur J Pharmacol S0014-2999 (13): 00254–00259.

Stalsberg H, Thomas DB, Rosenblatt KA, Jimenez LM, McTiernan A, Stemhagen A, Thompson WD, Curnen MG, Satariano W, Austin DF et al (1993) Histologic types and hormone receptors in breast cancer in men: a population-based study in 282 United States men. Cancer Causes Control 4: 143–151.

Turner KJ, Morley M, Atanassova N, Swanston ID, Sharpe RM (2000) Effect of chronic administration of an aromatase inhibitor to adult male rats on pituitary and testicular function and fertility. J Endocrinol 164: 225–238.

Visram H, Kanji F, Dent SF (2010) Endocrine therapy for male breast cancer: rates of toxicity and adherence. Curr Oncol 17: 17–21.

White J, Kearins O, Dodwell D, Horgan K, Hanby AM, Speirs V (2011) Male breast carcinoma: increased awareness needed. Breast Cancer Res 13: 219.

Zabolotny BP, Zalai CV, Meterissian SH (2005) Successful use of letrozole in male breast cancer: a case report and review of hormonal therapy for male breast cancer. J Surg Oncol 90: 26–30.

Zagouri F, Sergentanis TN, Chrysikos D, Zografos E, Rudas M, Steger G, Zografos G, Bartsch R (2013) Fulvestrant and male breast cancer: a case series. Ann Oncol 24: 265–266.

Acknowledgements

FZ receives a research grant from Hellenic Society for Medical Oncology (HeSMO).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zagouri, F., Sergentanis, T., Koutoulidis, V. et al. Aromatase inhibitors with or without gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue in metastatic male breast cancer: a case series. Br J Cancer 108, 2259–2263 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.255

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.255

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Male breast cancer: diagnosis stages, treatment and survival in a country with limited resources (Burkina Faso)

World Journal of Surgical Oncology (2018)

-

Analysis of the ATR-Chk1 and ATM-Chk2 pathways in male breast cancer revealed the prognostic significance of ATR expression

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Aromatase inhibitors with or without luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone agonist for metastatic male breast cancer: report of four cases and review of the literature

Breast Cancer (2016)

-

Efficacy of chemotherapy in metastatic male breast cancer patients: a retrospective study

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2015)

-

Role of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues in metastatic male breast cancer: results from a pooled analysis

Journal of Hematology & Oncology (2015)