Abstract

Background:

The mTOR-inhibitor everolimus improves progression-free survival in advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (PNETs). However, adaptive resistance to mTOR inhibition is described.

Methods:

QGP-1 and BON-1, two human PNET cell lines, were cultured with increasing concentrations of everolimus up to 22 weeks to reach a dose of 1 μ M everolimus, respectively, 1000-fold and 250-fold initial IC50. Using total DNA content as a measure of cell number, growth inhibitory dose–response curves of everolimus were determined at the end of resistance induction and over time after everolimus withdrawal. Response to ATP-competitive mTOR inhibitors OSI-027 and AZD2014, and PI3K-mTOR inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 was studied. Gene expression of 10 PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway-related genes was evaluated using quantitative real-time PCR (RT–qPCR).

Results:

Long-term everolimus-treated BON-1/R and QGP-1/R showed a significant reduction in everolimus sensitivity. During a drug holiday, gradual return of everolimus sensitivity in BON-1/R and QGP-1/R led to complete reversal of resistance after 10–12 weeks. Treatment with AZD2014, OSI-027 and NVP-BEZ235 had an inhibitory effect on cell proliferation in both sensitive and resistant cell lines. Gene expression in BON-1/R revealed downregulation of MTOR, RICTOR, RAPTOR, AKT and HIF1A, whereas 4EBP1 was upregulated. In QGP-1/R, a downregulation of HIF1A and an upregulation of ERK2 were observed.

Conclusions:

Long-term everolimus resistance was induced in two human PNET cell lines. Novel PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway-targeting drugs can overcome everolimus resistance. Differential gene expression profiles suggest different mechanisms of everolimus resistance in BON-1 and QGP-1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) are a diverse group of neoplasms, mainly found in the gastrointestinal tract, lung and pancreas. Pancreas NETs (PNETs) are relatively rare, with an incidence of 0.43 per 100 000 according to the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registry (Yao et al, 2008). However, this rate has doubled during the last 20 years (Lawrence et al, 2011; Fraenkel et al, 2012). Primary therapy for localised PNET remains surgical excision. However, up to 60% of all patients present with unresectable disease (Halfdanarson et al, 2008). In these patients, systemic treatment has an essential role in controlling the disease (Falconi et al, 2012). The role of traditional cytotoxic therapies in PNET remains a matter of debate, with only small series showing response to streptozocin-based chemotherapy (Calender, 1997; Hansel et al, 2004; Schonhoff et al, 2004). Newer chemotherapy regimens with temozolomide alone (Ekeblad et al, 2007), or in combination with capecitabine (Strosberg et al, 2011), show promise. The low response rate for streptozocin-based chemotherapy and the associated side effects underscore the need for targeted drugs.

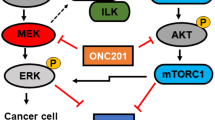

The phosphoinositide-3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K-Akt-mTOR) signalling pathway has a major role in NET by regulating cell growth, proliferation, survival and protein synthesis (Figure 1A). Furthermore, elevated mTOR expression and activity is associated with a higher proliferative capacity and worse prognosis (Missiaglia et al, 2010). Recently, exome sequencing of primary PNET tumour samples revealed mTOR pathway genes to be mutated in 16% of all PNETs, in addition to highlighting mutations in other genes, including MEN1 (44% of all patients), DAXX (25%) and ATRX (18%) (Jiao et al, 2011). mTOR acts as the catalytic subunit of two functionally distinct complexes, named mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) (Capdevila et al, 2011). mTOR proves to be an interesting target for therapy of PNET with mTOR-inhibiting rapamycin and analogues (rapalogues) such as everolimus (RAD001). Rapamycin, everolimus and other rapalogues form a complex with the 12 kD FK506-binding protein FKBP12 (Lach et al, 1999; Helpap and Kollermann, 2001). This rapalogue-FKBP12 complex allosterically inhibits mTOR when it is part of mTORC1. However, rapalogues only have limited effect on mTOR when mTOR is part of mTORC2 because of steric hindrance by the Rictor mTORC2-subunit (Goto et al, 2001). A phase III trial with everolimus was conducted in 410 patients with well- and moderately differentiated PNETs and showed an improvement in median progression-free survival (PFS) in the everolimus-treated group compared with the placebo group (Yao et al, 2011). Similar results were seen in the phase III trial with sunitinib, a pan-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (Raymond et al, 2011). On the basis of these results everolimus and sunitinib became the first FDA and EMA approved drugs in 30 years for the treatment of locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic PNETs. However, an objective partial response was only seen in 5% of the patients receiving everolimus or sunitinib. The significant effect on PFS was thus mainly due to disease stabilisation and minor reductions in tumour growth. As PFS in phase III study with everolimus is still limited to 11 months, adaptive resistance to mTOR inhibition with rapalogues was described (Yao et al, 2013). To overcome this resistance, novel PI3K-AKT-mTOR targeting drugs have been developed, such as NVP-BEZ235, OSI-027 and AZD2014. Exploiting the homology between the kinase domain of mTOR and PI3K, NVP-BEZ235 docks in the active pocket of both molecules and reduces kinase activity of PI3K and mTOR by competing with ATP-binding. The selective mTOR inhibitors AZD2014 and OSI-027 target the kinase domain of mTOR, blocking both mTORC1 and mTORC2 in an ATP-competitive manner, without blocking PI3K kinase activity (Maira et al, 2008; Yu et al, 2009). Although the efficacy of novel drugs in PNET cell line model of short-term adaptive resistance to everolimus has been studied (Passacantilli et al, 2014), no data are currently available about long-term adaptive resistance in everolimus-treated PNET. A better understanding of the mechanisms underlying resistance to rapalogues is thus necessary for a predictive biomarker for everolimus resistance to be identified.

Simplified representation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Constitutional activation of the pathway (A) and its response to rapalogues (B), ATP-competitive inhibitors (C) and dual PI3K-mTOR inhibitors (D) is shown. Red full lines describe an increase and red dashed lines show a decrease of feedback under different conditions. A detailed description can be found in the text.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

BON-1 and QGP-1, two human PNET cell line models, were used in this study. The BON-1 cell line was a kind gift from Dr Townsend (University of Texas Medical Brachn, Galveston, TX, USA; Townsend et al, 1993). The QGP-1 cell line was purchased from the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources Cell Bank (JRCB, Osaka, Japan; Kaku et al, 1980). BON-1 and QGP-1 cell line identity was confirmed using short tandem repeat profiling (Vandamme et al, 2015). The BON-1 cell line was cultured in 1 : 1 mixture of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) and F12 medium, supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), penicillin (1 × 105 units per l), fungizone (0.5 mg l−1), and L-glutamine (2 mmol l−1). The QGP-1 cell line was cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium, supplemented with 10% FCS and penicillin-streptomycin (1 × 105 units per l penicillin and 1 × 105 units per l streptomycin). All cell lines were incubated in an atmosphere of 95% humidity and 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Media and supplements were obtained from Life Technologies Bio-cult Europe (Invitrogen, Breda, The Netherlands).

Drugs and reagents

Everolimus (RAD001), AZD2014, OSI-027 and NVP-BEZ235 were purchased from Selleckchem (Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX, USA). Rapamycin was purchased from LG Laboratories (Woburn, MA, USA). All inhibitors were dissolved in 100% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) to a 1 mM concentration and stored in −20 °C. All drugs were diluted to working concentrations in 40% DMSO before use. In all the experiments, controls were treated with a vehicle DMSO concentration equivalent to the 0.4% final DMSO concentration in the treatment dilutions.

Cell proliferation assay using total DNA content

Cells were plated in 1 ml medium in 24-well plates at the density necessary to obtain a 70–80% cell confluence in the control groups at the end of the experiment. Medium was refreshed and the tested compounds were added to wells in quadruplicate after 24 h for QGP-1 and 72 h for BON-1. Time points were chosen to reduce inter- and intra-experiment variability. The concentrations of compounds tested ranged between 0,1 nM and 1 μ M for everolimus, rapamycin and NVP-BEZ235. Given the narrow therapeutic margin of AZD2014 and OSI-027, the used concentrations ranged from 10 nM to 1 μ M with an added 250 nM and 500 nM concentration. Every 3 days, the cells were supplied with fresh medium and compounds. After 7 days of treatment, the cells were harvested for DNA measurement. Measurement of total DNA content, as a measure of cell number, was performed with the bisbenzimide DNA-intercalating fluorescent dye (Hoechst 33258; Boehring Diagnostics, La Jolla, CA, USA) as previously described (Barrett et al, 1995).

Quantitative real-time PCR of PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway genes

The tested cell line conditions were plated in 3 ml medium in six-well plates at the density required to obtain 70–80% cell confluence at the end of the experiment. Twenty-four hours later for QGP-1 cell line conditions and 72 h later for BON-1 cell line conditions, medium was replaced and cells were incubated for 72 h with vehicle. One-step reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT–qPCR) was performed on total RNA from six biological replicates in a single reaction using the Power SYBR Green RNA-To-CT 1-Step kit (Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) on a LightCycler 480 instrument (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany). Primers were designed using QuantPrime software (Arvidsson et al, 2008) and RTPrimerDB (http://www.rtprimerdb.org) and have been obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Leuven, Belgium) (Supplementary Table 1). All reactions have been performed in triplicates in 384-well plates with 2 μl total RNA (prediluted to 15 ng μl−1) as input in a total reaction volume of 10 μl, further comprising 5 μl Power SYBR Green RT-PCR Mix (2 × ; Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 0.08 μl RT Enzyme Mix (125 × ; Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 200 nM of each primer (final concentration).

Statistical analysis

All cell proliferation assays were performed at least twice at different times. The repeated experiments gave comparable results. The comparative statistical evaluations between the different cell line conditions were performed by two-way ANOVA with treatment concentration and cell line condition as variables. For post hoc testing, a multiple comparative test with Dunn–Šidák correction was used. For RT–qPCR experiments, normalised relative gene expression values were calculated using qBasePLUS software version 1.5 (Biogazelle, Zwijnaarde, Belgium). Messenger RNA expression was normalised to household gene expression (GAPDH and RPL13A for BON-1; HPRT and YWAZ for QGP-1) according to the geNorm algorithm (Mestdagh et al, 2009). Comparison between gene expression levels was done by Student’s t-test and adjusted for multiple testing using Holm–Bonferroni correction. All statistical analyses were done using GraphPad Prism 5.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

Inducing everolimus resistance

In untreated human PNET cell lines BON-1 and QGP-1, the everolimus concentration that reduces growth by 50% (IC50) after 7 days of treatment was 1 and 4 nM, respectively (data not shown). Starting from this IC50 concentration, QGP-1 and BON-1 were continuously cultured in increasing concentrations of everolimus. The everolimus concentration was progressively doubled every 14 days during 8–10 dose doublings until a final concentration of 1 μ M was reached. In parallel, clonal BON-1 and QGP-1 cells were long-term vehicle treated. The established long-term everolimus-treated cell lines (BON-1/R and QGP-1/R) were maintained in the maximally achieved everolimus concentration. No morphological changes were seen between the long-term vehicle-treated cell lines and the long-term everolimus-treated cell lines (Supplementary Figure 2). After the establishment of the long-term everolimus-treated BON-1/R and QGP-1/R, both showed a statistically significant reduced growth inhibitory response to everolimus in comparison with long-term vehicle-treated BON-1 and QGP-1 at everolimus concentrations between 10 nM and 1 μ M for BON-1/R and at 1 nM and 1 μ M for QGP-1/R, respectively (Figure 2A and B). In addition, BON-1/R and QGP-1/R had a significantly reduced sensitivity to rapamycin in concentrations ranging from 1 nM to 1 μ M when compared with their long-term vehicle-treated BON-1 and QGP-1 counterparts (Figure 2C and D).

Everolimus dose response curves of QGP-1/R and long-term vehicle-treated QGP-1 and BON-1/R and long-term vehicle-treated BON-1. All cells were treated for 7 days with increasing concentrations of everolimus (A, B) or rapamycin (C, D), respectively. Growth inhibitory response is expressed as the percentage of vehicle-treated control (±s.e.m.). Control is normalised at 100%.

Evolution of everolimus-resistance over time

In order to study reversibility of everolimus-resistance, the BON-1/R and QGP-1/R cell lines were cultured without everolimus maintenance treatment during 10 and 12 weeks, respectively, showing a gradual return of everolimus sensitivity (data not shown). After 10–12 weeks, this resulted in the BON-1/R STOP and QGP-1/R STOP cell line conditions. When comparing these cell line conditions with BON-1/R and QGP-1/R, maintained during 10–12 weeks at maximum 1 μ M everolimus concentration, and vehicle-treated BON-1 and QGP-1, a return of BON-1/R STOP and QGP-1/R STOP to the sensitivity levels of BON-1 and QGP-1 was observed (Figure 3A and B).

Everolimus dose response curves after 10 to 12 weeks of wash-out. Response was evaluated after 7 days of treatment with increasing everolimus concentrations in BON-1/R, long-term vehicle-treated BON-1, and BON-1/R after an everolimus wash-out period of 12 weeks (BON-1/R STOP) (A) and QGP-1/R, and in long-term vehicle-treated QGP-1/ and QGP-1/R after an everolimus wash-out period of 10 weeks (QGP-1/R STOP) (B). Growth inhibitory response is expressed as the percentage of vehicle-treated control (±s.e.m.). Control is normalised at 100%. P-values shown are for Dunn Sídák post hoc comparison after two-way ANOVA between BON-1/R and QGP-1/R and BON-1/R STOP and QGP-1/R STOP, respectively.

Overcoming everolimus-resistance

A dose–response study in both everolimus-resistant and -sensitive BON-1 and QGP-1 cells to the growth inhibitory effect of AZD2014, OSI-027 and NVP-BEZ235 was executed in parallel. After a 7-day-treatment with AZD2014, cell proliferation was significantly less reduced at the 250 nM and 500 nM concentration of AZD2014 in BON-1/R when compared with long-term vehicle-treated BON-1. When exposing QGP-1/R and QGP-1 to AZD2014 during 7 days, growth reduction was significantly more pronounced in long-term vehicle-treated QGP-1 when compared with QGP-1/R in all tested AZD2014 concentrations above 100 nM. A maximal inhibition of >80% of cell proliferation was obtained at 1 μ M of AZD2014 in all cell lines tested (Figure 4A and B). BON-1/R and long-term vehicle-treated BON-1 did not respond significantly different to OSI-027, while QGP-1/R was more resistant to OSI-027 than QGP-1 in all concentrations tested above 100 nM. The maximum inhibition with OSI-027 reached in BON-1/R, BON-1 and QGP-1 cells was a 50% reduction of cell proliferation (Figure 4C and D). No statistically significant difference in the inhibition of cell proliferation was observed after 7 days of treatment with NVP-BEZ235 in BON-1/R when compared with long-term vehicle-treated BON-1 in the 1 nM to 1 μ M NVP-BEZ235 concentration range. In both everolimus-sensitive and -resistant BON-1 cells, a maximum inhibition of >92% of control cell proliferation was reached at 100 nM of NVP-BEZ235. When comparing the QGP-1/R and QGP-1, NVP-BEZ235 was less potent at 10 nM, compared with QGP-1/R cells. Maximal cell growth inhibition was achieved a 100 nM in both QGP-1/R and long-term vehicle-treated QGP-1 (Figure 4E and F).

Dose–response curves with novel PI3K-Akt-mTOR inhibitors in BON-1/R and long-term vehicle-treated BON-1 and QGP-1/R and long-term vehicle-treated QGP-1. Cells were treated during 7 days with, respectively, AZD2014 (A, B), OSI-027 (C, D) and NVP-BEZ235 (E, F). Response is expressed as the percentage of vehicle-treated control (±s.e.m.). Control is normalised at 100%.

Gene expression changes in everolimus resistance

Differential gene expression of MTOR, RAPTOR, RICTOR, AKT, S6K1, 4EBP1, ERK1, ERK2, BCL2 and HIF1A between BON-1/R and long-term vehicle-treated BON-1 showed a significant downregulation of MTOR, RICTOR, RAPTOR, AKT and HIF1A, whereas 4EBP1 was significantly upregulated (P<0.05) (Figure 5). When comparing QGP-1/R and QGP-1, a significant downregulation of HIF1A and a significant upregulation of ERK2 were observed (P<0.05).

Changes in mRNA expression between resistant and sensitive cell lines. Changes are expressed in mean percentage±s.e.m between BON-1/R and BON-1 and QGP-1/R (A) and QGP-1 (B). In addition to MTOR, mTORC1 component RAPTOR and mTORC2 component RICTOR expression was studied. Moreover, gene expression of AKT, encoding the mTOR upstream AKT, S6K1 and 4EBP1, encoding the mTOR downstream p70 ribosomal kinase 1 (S6K1) and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1), respectively, was determined. In addition, BCL2, a gene encoding for anti-apoptotic protein B-cell leukaemia 2 (Bcl-2), and HIF1A, encoding the hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha protein (HIF-1 alpha) was used to study the overall effect on apoptosis and proliferation in the cell. Finally, expression of ERK1 and ERK2, two components of the MAPK-ERK pathway was determined. Differences were tested using Student's t-test. P<0.05, after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing, was considered significant (hatched bars).

Discussion

In this study, to the best of our knowledge, the first two PNET models for long-term acquired everolimus resistance were established. Both QGP-1 and BON-1 were cultured during more than 20 weeks in increasing concentrations of everolimus and continued to grow under a 250 and 1000-fold IC50 growth inhibitory concentration of everolimus, respectively. Corresponding in vivo concentrations are not reachable in patients (O’Donnell et al, 2008). Continued cell growth under these high everolimus concentrations, unreachable in patients, hence indicates an everolimus resistance with possible clinical implications. Both the resulting BON-1/R and QGP-1/R show a significantly decreased response to everolimus in comparison with long-term vehicle-treated BON-1 and QGP-1, even in the highest concentrations tested (1 μ M). Similar results were seen when comparing BON-1/R and QGP-1/R and its vehicle-treated counterparts for response to rapamycin. This indicates that BON-1/R and QGP-1/R are not only everolimus-resistant, but are also resistant to other rapalogues. A previous study looked at everolimus-resistance in BON-1 (Passacantilli et al, 2014). However, this study treated BON-1 cells during 8 weeks with a dose of 10 nM, which is a much shorter period and a lower dose than used in this study. In addition, the authors did not perform a resistance induction experiment with QGP-1. Given the long duration of treatment, the resulting BON-1/R and QGP-1/R cell lines in our study could be considered as a representative model for rapalogue resistance seen in PNET patients, where median time to treatment failure and, thus, acquired everolimus resistance is 11 months (Yao et al, 2011).

Various mechanisms have been proposed for the limited response to everolimus in PNET (Figure 1B). Not all phosphorylation sites of mTORC1 downstream proteins such as p70 ribosomal S6 kinase 1 (S6K1), growth factor receptor bound protein 10 (GRB10) and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) respond to the same extent to allosteric inhibition of mTORC1 by rapalogues(Kang et al, 2013), thereby diminishing rapalogue efficacy. Adaptive resistance may also be caused by induction of activated phosphorylation of AKT. This occurs through the lifting of negative feedback of the mTORC1 downstream p70 ribosomal S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) on the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway(Ohike et al, 2003; O’Reilly et al, 2006; Julien et al, 2010). S6K1 effects this negative-feedback on insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1), which regulates insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-1; O’Reilly et al, 2006). Furthermore, mTORC1 activates GRB10, which negatively regulates IGF-1 signalling. When mTORC1 is inhibited by rapalogues, this negative feedback-loop of IGF-1 is suppressed, synergistically adding to the effect of mTOR inhibition of the S6K1-feedback loop (Emerling and Akcakanat, 2011). As rapalogues effectively block mTORC1 but only have a limited, dose-dependent action on the mTORC2, the effect of rapalogues on mTOR signalling may be circumvented through increased activity of mTORC2 (O’Reilly et al, 2006; Julien et al, 2010). Furthermore, a direct role of S6K1 on mTORC2-mediated AKT phosphorylation has been described since S6K1 might be instrumental in the inhibitory phosphorylation of Rictor, the rapalogue-insensitive component of mTORC2 (Julien et al, 2010). Novel mTOR inhibitors, blocking both mTORC1 and mTORC2 by competitively binding the ATP-binding mTOR kinase pocket, have been developed to overcome these escape mechanisms. AZD2014 is an ATP-competitive mTOR inhibitor, currently undergoing phase II evaluation in different tumour types (Pike et al, 2013; Basu et al, 2015a) (Figure 1C). In our study, AZD2014 effectively reduces cell proliferation both in the everolimus-sensitive QGP-1 and BON-1, as well as in the everolimus-resistant BON-1/R and QGP-1/R. This is the first time that AZD2014 shows efficacy in PNET models. In addition, these results indicate that AZD2014 overcomes everolimus resistance in PNET in concentrations reachable in patients (Basu et al, 2015a). Further development of this drug in PNET could hence benefit PNET patients. In addition, OSI-027, a drug from the same ATP-competitive mTOR inhibiting class was tested. In contrast with the other tested compounds, the growth inhibitory effect of OSI-027 in the concentration ranges tested reaches growth inhibition by only 50% at 1 μ M in vehicle-treated BON-1 and QGP-1 cell lines. In a xenograft mouse model, concentrations of up to 2 μ M could be reached, but further studies on pharmacokinetics in humans are needed (Bhagwat et al, 2011). Although resistant and sensitive BON-1 responded equally to OSI-027 treatment, only limited efficacy in overcoming everolimus resistance with OSI-027 was observed in the QGP-1 cell line. This difference in response to OSI-027 between BON-1/R and QGP-1/R suggests two distinct molecular mechanisms of resistance. NVP-BEZ235 is a dual blocker of mTOR, blocking both mTORC1 and mTORC2, and the upstream PI3K (Doglioni et al, 1998) (Figure 1D). NVP-BEZ235 has proven efficacy in in vitro and in vivo PNET models (Doglioni et al, 1998; Paireder et al, 2013). Dual inhibition of the PI3K-mTOR pathway could prevent cross-talk activation of the mitogen-activated kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MAPK-ERK pathway) through PI3K-mediated feedback loop (Helpap and Kollermann, 1999; Carracedo et al, 2008; Zitzmann et al, 2010; Svejda et al, 2011; Paireder et al, 2013). This cross-talk could lead to an escape of mTORC1 inhibition and, hence, to rapalogue resistance. Although NVP-BEZ235 has completed phase II studies, clinical development of this drug might not progress to phase III because of the drug’s safety profile (Fazio et al, 2016). However, our current study demonstrates that dual blocking of PI3K and mTOR could be an attractive strategy to overcome long-term acquired everolimus resistance. In addition, maximum inhibition in both resistant and sensitive cell lines was reached with NVP-BEZ235 concentrations more than 10-fold lower than dose-limiting plasma concentrations obtained in phase I studies (Bendell et al, 2015). As this is in line with previously reported in vitro results and an in vivo study with lower dose NVP-BEZ235 in a glioblastoma model demonstrated efficacy, it could hence be interesting to evaluate low-dose NVP-BEZ235 in PNET (Maira et al, 2008; Passacantilli et al, 2014).

Another possible mechanism for everolimus resistance is tumour heterogeneity. Within-patient and within-tumour heterogeneity in proliferation, genomic alterations and functional imaging characteristics have been demonstrated in neuroendocrine tumour patients (Gebauer et al, 2014; Shi et al, 2015; Basu et al, 2015b). This heterogeneity could be caused by tumoural subclones with different phenotypes and responses to treatement (Marusyk et al, 2014). By treating a patient with everolimus, selection of everolimus-resistant subclones could occur, leading to resistance. Although short-term everolimus resistance is mainly driven by phosphorylation changes in PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway proteins (O’Reilly et al, 2006), a shift in clonal population could be a driving force in long-term everolimus resistance. This is illustrated by the gradual reversal of everolimus resistance in BON-1/R and QGP-1/R, with a complete return of everolimus sensitivity only after >2 months of culturing without everolimus. If this resistance would only be caused by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of proteins, a faster reversal of everolimus resistance could be expected. Long-term treatment with everolimus might hence select or induce subclones with a different genetic, epigenetic or transcriptional make-up that makes them more resistant to everolimus. Future studies using next generation sequencing would be a good strategy to identify these resistant subclones and yield biomarkers for everolimus resistance. Given the long timeframe of sustained resistance, alterations in gene expression were studied to elucidate possible resistance mechanisms. In BON-1/R, the main components of both mTORC1 and mTORC2 and the important upstream protein AKT were downregulated, whereas effector protein 4EBP1 expression was upregulated, hinting at a compensatory mechanism in which 4EBP1 is less dependent on mTORC1 and mTORC2. On the other hand, the main upregulated gene in QGP-1/R was ERK2, part of the MAPK-ERK pathway, illustrating a possible escape through this pathway. Interestingly, both cell lines seem to have a differential gene expression profile after developing resistance to everolimus. This is corroborated by their different response to novel PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway targeting drugs. QGP-1/R is more resistant to treatment with the two tested ATP-competitive mTOR inhibitors, AZD2014 and OSI-027, than BON-1/R. Similarly, although full inhibition of proliferation with NVP-BEZ235 could be reached in both BON-1/R and QGP-1/R, a higher concentration of NVP-BEZ235 is needed to overcome resistance in QGP-1/R. Hence, we could conclude that the underlying mechanisms of everolimus resistance in BON-1/R and QGP-1/R might be different. If our data can be extrapolated to PNET patients, our study could provide an insight in the mechanisms determining resistance to mTOR inhibition in the clinic. Ultimately, this might lead to a better selection of patients and true personalised medicine.

In conclusion, the first PNET models for long-term everolimus treatment, resulting in acquired rapalogue-resistance, are presented here. Both the ATP-competitive mTOR blocker, AZD2014, as the dual PI3K-mTOR blocker NVP-BEZ235 are able to overcome this rapalogue resistance. Further evaluation of both drugs in in vivo and patient studies, targeted at overcoming everolimus resistance, could hence be challenging. In addition, both models allow the study of the detailed mechanisms of acquired resistance in PNET. Expanding these studies with advanced genetic and genomic techniques, such as next generation sequencing, could lead to the identification of biomarkers for everolimus resistance.

Change history

15 March 2016

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Arvidsson S, Kwasniewski M, Riano-Pachon DM, Mueller-Roeber B (2008) QuantPrime—a flexible tool for reliable high-throughput primer design for quantitative PCR. BMC Bioinformatics 9: 465.

Barrett P, Hobbs RC, Coates PJ, Risdon RA, Wright NA, Hall PA (1995) Endocrine cells of the human gastrointestinal tract have no proliferative capacity. Histochem J 27 (6): 482–486.

Basu B, Dean E, Puglisi M, Greystroke A, Ong M, Burke WM, Cavallin M, Bigley G, Womack C, Harrington EA, Green S, Oelmann E, de Bono JS, Ranson MR, Banerji U (2015a) First-in-human pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the dual m-TORC 1/2 inhibitor, AZD2014. Clin Cancer Res 21 (15): 3412–3419.

Basu S, Ranade R, Thapa P (2015b) Correlation and discordance of tumour proliferation index and molecular imaging characteristics and their implications for treatment decisions and outcome pertaining to peptide receptor radionuclide therapy in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumour: developing a personalized model. Nucl Med Commun 36 (8): 766–774.

Bendell JC, Kurkjian C, Infante JR, Bauer TM, Burris HA 3rd, Greco FA, Shih KC, Thompson DS, Lane CM, Finney LH, Jones SF (2015) A phase 1 study of the sachet formulation of the oral dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor BEZ235 given twice daily (BID) in patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest New Drugs 33 (2): 463–471.

Bhagwat SV, Gokhale PC, Crew AP, Cooke A, Yao Y, Mantis C, Kahler J, Workman J, Bittner M, Dudkin L, Epstein DM, Gibson NW, Wild R, Arnold LD, Houghton PJ, Pachter JA (2011) Preclinical characterization of OSI-027, a potent and selective inhibitor of mTORC1 and mTORC2: distinct from rapamycin. Mol Cancer Ther 10 (8): 1394–1406.

Calender A (1997) [Recent data on molecular genetics of neuroendocrine tumors]. Ann Endocrinol 58 (2): 113–123.

Capdevila J, Salazar R, Halperin I, Abad A, Yao JC (2011) Innovations therapy: mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors for the treatment of neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer Metastasis Rev 30 (Suppl 1): 27–34.

Carracedo A, Ma L, Teruya-Feldstein J, Rojo F, Salmena L, Alimonti A, Egia A, Sasaki AT, Thomas G, Kozma SC, Papa A, Nardella C, Cantley LC, Baselga J, Pandolfi PP (2008) Inhibition of mTORC1 leads to MAPK pathway activation through a PI3K-dependent feedback loop in human cancer. J Clin Invest 118 (9): 3065–3074.

Doglioni C, Chiarelli C, Macri E, Dei Tos AP, Meggiolaro E, Dalla Palma P, Barbareschi M (1998) Cyclin D3 expression in normal, reactive and neoplastic tissues. J Pathol 185 (2): 159–166.

Ekeblad S, Sundin A, Janson ET, Welin S, Granberg D, Kindmark H, Dunder K, Kozlovacki G, Orlefors H, Sigurd M, Oberg K, Eriksson B, Skogseid B (2007) Temozolomide as monotherapy is effective in treatment of advanced malignant neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Cancer Res 13 (10): 2986–2991.

Emerling BM, Akcakanat A (2011) Targeting PI3K/mTOR signaling in cancer. Cancer Res 71 (24): 7351–7359.

Falconi M, Bartsch DK, Eriksson B, Kloppel G, Lopes JM, O’Connor JM, Salazar R, Taal BG, Vullierme MP, O’Toole D Barcelona Consensus Conference p (2012) ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms of the digestive system: well-differentiated pancreatic non-functioning tumors. Neuroendocrinology 95 (2): 120–134.

Fazio N, Buzzoni R, Baudin E, Antonuzzo L, Hubner RA, Lahner H, DE Herder WW, Raderer M, Teulé A, Capdevila J, Libutti SK, Kulke MH, Shah M, Dey D, Turri S, Aimone P, Massacesi C, Verslype C (2016) A Phase II Study of BEZ235 in Patients with Everolimus-resistant, Advanced Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumours. Anticancer Res 36 (2): 713–719.

Fraenkel M, Kim MK, Faggiano A, Valk GD (2012) Epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 26 (6): 691–703.

Gebauer N, Schmidt-Werthern C, Bernard V, Feller AC, Keck T, Begum N, Rades D, Lehnert H, Brabant G, Thorns C (2014) Genomic landscape of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. World J Gastroenterol 20 (46): 17498–17506.

Goto K, Kodama T, Matsuno Y, Yokose T, Asamura H, Kamiya N, Shimosato Y (2001) Clinicopathologic and DNA cytometric analysis of carcinoid tumors of the thymus. Mod Pathol 14 (10): 985–994.

Halfdanarson TR, Rubin J, Farnell MB, Grant CS, Petersen GM (2008) Pancreatic endocrine neoplasms: epidemiology and prognosis of pancreatic endocrine tumors. Endocr Relat Cancer 15 (2): 409–427.

Hansel DE, Wilentz RE, Yeo CJ, Schulick RD, Montgomery E, Maitra A (2004) Expression of neuropilin-1 in high-grade dysplasia, invasive cancer, and metastases of the human gastrointestinal tract. Am J Surg Pathol 28 (3): 347–356.

Helpap B, Kollermann J (1999) Undifferentiated carcinoma of the prostate with small cell features: immunohistochemical subtyping and reflections on histogenesis. Virchows Arch 434 (5): 385–391.

Helpap B, Kollermann J (2001) Immunohistochemical analysis of the proliferative activity of neuroendocrine tumors from various organs. Are there indications for a neuroendocrine tumor-carcinoma sequence? Virchows Arch 438 (1): 86–91.

Jiao Y, Shi C, Edil BH, de Wilde RF, Klimstra DS, Maitra A, Schulick RD, Tang LH, Wolfgang CL, Choti MA, Velculescu VE, Diaz LA Jr, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW, Hruban RH, Papadopoulos N (2011) DAXX/ATRX, MEN1, and mTOR pathway genes are frequently altered in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Science 331 (6021): 1199–1203.

Julien LA, Carriere A, Moreau J, Roux PP (2010) mTORC1-activated S6K1 phosphorylates Rictor on threonine 1135 and regulates mTORC2 signaling. Mol Cell Biol 30 (4): 908–921.

Kaku M, Nishiyama T, Yagawa K, Abe M (1980) Establishment of a carcinoembryonic antigen-producing cell line from human pancreatic carcinoma. Gan 71 (5): 596–601.

Kang SA, Pacold ME, Cervantes CL, Lim D, Lou HJ, Ottina K, Gray NS, Turk BE, Yaffe MB, Sabatini DM (2013) mTORC1 phosphorylation sites encode their sensitivity to starvation and rapamycin. Science 341 (6144): 1236566.

Lach B, Gregor A, Rippstein P, Omulecka A (1999) Angiogenic histogenesis of stromal cells in hemangioblastoma: ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study. Ultrastruct Pathol 23 (5): 299–310.

Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Chan A, Svejda B, Kidd M, Modlin IM (2011) The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 40 (1): 1–18,, vii.

Maira SM, Stauffer F, Brueggen J, Furet P, Schnell C, Fritsch C, Brachmann S, Chene P, De Pover A, Schoemaker K, Fabbro D, Gabriel D, Simonen M, Murphy L, Finan P, Sellers W, Garcia-Echeverria C (2008) Identification and characterization of NVP-BEZ235, a new orally available dual phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor with potent in vivo antitumor activity. Mol Cancer Ther 7 (7): 1851–1863.

Marusyk A, Tabassum DP, Altrock PM, Almendro V, Michor F, Polyak K (2014) Non-cell-autonomous driving of tumour growth supports sub-clonal heterogeneity. Nature 514 (7520): 54–58.

Mestdagh P, Van Vlierberghe P, De Weer A, Muth D, Westermann F, Speleman F, Vandesompele J (2009) A novel and universal method for microRNA RT-qPCR data normalization. Genome Biol 10 (6): R64.

Missiaglia E, Dalai I, Barbi S, Beghelli S, Falconi M, della Peruta M, Piemonti L, Capurso G, Di Florio A, delle Fave G, Pederzoli P, Croce CM, Scarpa A (2010) Pancreatic endocrine tumors: expression profiling evidences a role for AKT-mTOR pathway. J Clin Oncol 28 (2): 245–255.

O’Donnell A, Faivre S, Burris HA 3rd, Rea D, Papadimitrakopoulou V, Shand N, Lane HA, Hazell K, Zoellner U, Kovarik JM, Brock C, Jones S, Raymond E, Judson I (2008) Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the oral mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 26 (10): 1588–1595.

O’Reilly KE, Rojo F, She QB, Solit D, Mills GB, Smith D, Lane H, Hofmann F, Hicklin DJ, Ludwig DL, Baselga J, Rosen N (2006) mTOR inhibition induces upstream receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and activates Akt. Cancer Res 66 (3): 1500–1508.

Ohike N, Jurgensen A, Pipeleers-Marichal M, Kloppel G (2003) Mixed ductal-endocrine carcinomas of the pancreas and ductal adenocarcinomas with scattered endocrine cells: characterization of the endocrine cells. Virchows Arch 442 (3): 258–265.

Paireder S, Werner B, Bailer J, Werther W, Schmid E, Patzak B, Cichna-Markl M (2013) Comparison of protocols for DNA extraction from long-term preserved formalin fixed tissues. Anal Biochem 439 (2): 152–160.

Passacantilli I, Capurso G, Archibugi L, Calabretta S, Caldarola S, Loreni F, Delle Fave G, Sette C (2014) Combined therapy with RAD001 e BEZ235 overcomes resistance of PET immortalized cell lines to mTOR inhibition. Oncotarget 5 (14): 5381–5391.

Pike KG, Malagu K, Hummersone MG, Menear KA, Duggan HM, Gomez S, Martin NM, Ruston L, Pass SL, Pass M (2013) Optimization of potent and selective dual mTORC1 and mTORC2 inhibitors: the discovery of AZD8055 and AZD2014. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 23 (5): 1212–1216.

Raymond E, Dahan L, Raoul JL, Bang YJ, Borbath I, Lombard-Bohas C, Valle J, Metrakos P, Smith D, Vinik A, Chen JS, Horsch D, Hammel P, Wiedenmann B, Van Cutsem E, Patyna S, Lu DR, Blanckmeister C, Chao R, Ruszniewski P (2011) Sunitinib malate for the treatment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med 364 (6): 501–513.

Schonhoff SE, Giel-Moloney M, Leiter AB (2004) Minireview: Development and differentiation of gut endocrine cells. Endocrinology 145 (6): 2639–2644.

Shi C, Gonzalez RS, Zhao Z, Koyama T, Cornish TC, Hande KR, Walker R, Sandler M, Berlin J, Liu EH (2015) Liver metastases of small intestine neuroendocrine tumors: Ki-67 heterogeneity and World Health Organization grade discordance with primary tumors. Am J Clin Pathol 143 (3): 398–404.

Strosberg JR, Fine RL, Choi J, Nasir A, Coppola D, Chen DT, Helm J, Kvols L (2011) First-line chemotherapy with capecitabine and temozolomide in patients with metastatic pancreatic endocrine carcinomas. Cancer 117 (2): 268–275.

Svejda B, Kidd M, Kazberouk A, Lawrence B, Pfragner R, Modlin IM (2011) Limitations in small intestinal neuroendocrine tumor therapy by mTor kinase inhibition reflect growth factor-mediated PI3K feedback loop activation via ERK1/2 and AKT. Cancer 117 (18): 4141–4154.

Townsend CM Jr, Ishizuka J, Thompson JC (1993) Studies of growth regulation in a neuroendocrine cell line. Acta Oncol (Madr) 32 (2): 125–130.

Vandamme T, Peeters M, Dogan F, Pauwels P, Van Assche E, Beyens M, Mortier G, Vandeweyer G, de Herder W, Van Camp G, Hofland LJ, Op de Beeck K (2015) Whole-exome characterization of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor cell lines BON-1 and QGP-1. J Mol Endocrinol 54 (2): 137–147.

Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, Dagohoy C, Leary C, Mares JE, Abdalla EK, Fleming JB, Vauthey JN, Rashid A, Evans DB (2008) One hundred years after "carcinoid": epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol 26 (18): 3063–3072.

Yao JC, Phan AT, Jehl V, Shah G, Meric-Bernstam F (2013) Everolimus in advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: the clinical experience. Cancer Res 73 (5): 1449–1453.

Yao JC, Shah MH, Ito T, Bohas CL, Wolin EM, Van Cutsem E, Hobday TJ, Okusaka T, Capdevila J, de Vries EG, Tomassetti P, Pavel ME, Hoosen S, Haas T, Lincy J, Lebwohl D, Oberg K Rad001 in Advanced Neuroendocrine Tumors TTSG (2011) Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med 364 (6): 514–523.

Yu K, Toral-Barza L, Shi C, Zhang WG, Lucas J, Shor B, Kim J, Verheijen J, Curran K, Malwitz DJ, Cole DC, Ellingboe J, Ayral-Kaloustian S, Mansour TS, Gibbons JJ, Abraham RT, Nowak P, Zask A (2009) Biochemical, cellular, and in vivo activity of novel ATP-competitive and selective inhibitors of the mammalian target of rapamycin. Cancer Res 69 (15): 6232–6240.

Zitzmann K, Ruden J, Brand S, Goke B, Lichtl J, Spottl G, Auernhammer CJ (2010) Compensatory activation of Akt in response to mTOR and Raf inhibitors - a rationale for dual-targeted therapy approaches in neuroendocrine tumor disease. Cancer Lett 295 (1): 100–109.

Acknowledgements

The BON-1 cell line was a kind gift from J.C. Thompson, Department of Surgery, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX, USA to Leo J. Hofland, Section of Endocrinology, Department of Internal Medicine, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands for research purposes. This work was supported by the Flemish Agency of Scientifc Research (FWO grant G.0327.13N) and the ENETS-Ipsen 2013 Translational Research Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

TV, WdH and MP: advisory role and speakers’ fees for Ipsen and Novartis. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Vandamme, T., Beyens, M., de Beeck, K. et al. Long-term acquired everolimus resistance in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours can be overcome with novel PI3K-AKT-mTOR inhibitors. Br J Cancer 114, 650–658 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.25

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.25

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Novel RICTOR amplification harbouring entities: FISH validation of RICTOR amplification in tumour tissue after next-generation sequencing

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor progression and resistance to everolimus: the crucial role of NF-kB and STAT3 interplay

Journal of Endocrinological Investigation (2023)

-

eIF3a regulation of mTOR signaling and translational control via HuR in cellular response to DNA damage

Oncogene (2022)

-

Establishment and characterization of the third non-functional human pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor cell line

Human Cell (2022)

-

Moderne molekulare und bildgebende Diagnostik bei neuroendokrinen Neoplasien des Pankreas

best practice onkologie (2022)