Abstract

Purpose

To report clinical features, topographic findings and outcome of 10 eyes with peripapillary schisis in open-angle glaucoma.

Patients and methods

A retrospective review of patients with open-angle glaucoma who were noted to have peripapillary schisis on optical coherence tomography (OCT) were included. Serial peripapillary and macula infrared and OCT images, visual acuity, visual fields, and schisis appearance were reviewed.

Results

Ten eyes of nine patients with open-angle glaucoma were detected to have the presence of peripapillary schisis. Nerve fibre layer schisis was detected in all eyes and one eye had an associated macular schisis. None of the eyes had an acquired pit of the optic nerve or pathological myopia. The mean intraocular pressures at detection was 18.3±4.3 mm Hg and the schisis resolved in four eyes after a mean follow-up of 21.2±8.8 months. Visual field worsening was noted in 4 of the 10 eyes and the resolution of schisis resulted in significant reduction in the retinal nerve fibre layer (RNFL) thickness.

Conclusions

Peripapillary schisis detected during the normal course of open-angle glaucoma can resolve spontaneously and rarely involves the macula. Its resolution leads to reduction in RNFL thickness; therefore, caution is advised while interpreting serial scans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Peripapillary schisis is known to occur in various glaucoma entities namely primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG),1 normal-tension glaucoma,2 pseudoexfoliation,3 intermittent, and angle-closure glaucoma.4 This condition is often overlooked in routine clinical practice as it resolves spontaneously and patients remain asymptomatic. A literature review on this subject reveals only one large case series from the Investigating Glaucoma Progression Study in Korea. This study of 22 eyes showed that the schisis is attached to the optic nerve and topographically correlates with retinal nerve fibre layer (RNFL) defect.1 We report here clinical features and final outcome of 10 eyes with peripapillary schisis in open-angle glaucoma in Caucasian eyes.

Materials and methods

In this observational study, ten eyes of nine patients were detected to have peripapillary schisis during their routine glaucoma monitoring. They were prospectively followed up to document the course of the schisis. Clinical history, intraocular pressures (IOP), and visual fields were obtained from the electronic patients’ record. The infrared and SD-OCT (spectral domain optical coherent tomography) of the optic nerve, circumpapillary region, and macula done at baseline and at each subsequent visit were reviewed. The results reported here are from the last follow-up visit.

Results

Of the 10 eyes (nine patients, one with bilateral involvement) with peripapillary schisis, there were four males and five females (mean age, 71±6.2 years). The primary diagnoses were POAG in five and normal-tension glaucoma in four patients (Table 1). The mean IOP at the time of its first detection was 18.3±4.3 mm Hg. The schisis was attached to the optic nerve head in all eyes and an associated macular schisis was noted in one eye (eye nine). Altogether, 14 peripapillary schitic areas were noted in the absence of vitreo-macular traction.

Cases

Bilateral peripapillary schisis (eye two and three)

A 69-year-old male patient diagnosed with POAG was noted to have peripapillary schisis in both eyes of variable degree. The IOP at detection was 16 and 22 mm Hg in right and left eye, respectively. Over the 39 months follow-up, the schisis and the IOP remained unchanged in the right eye, whereas the left eye showed its partial resolution (Figure 1) along with reduction of IOP to 11 mm Hg. The visual fields in both eyes however remained unchanged. The RNFL thickness in the right eye remained unchanged at 208 μ and in the left eye reduced from 294 to 46 μ.

Resolved peripapillary schisis (eye four)

A 69-year-old male patient with newly diagnosed POAG was noted to have peripapillary schisis inferotemporal to the optic nerve, on the first visit. The presenting IOP was 19 mm Hg that reduced to 11 mm Hg, with a complete resolution of the schisis cavity over 11 months of follow-up (Figure 2). The RNFL thickness reduced from 135 to 70 μ with no corresponding change on visual field.

Peripapillary schisis with macular involvement (eye nine)

A 76-year-old female with POAG was noted to have extensive peripapillary schisis (270°) around the disc along with macular schisis in her right eye (Figure 3). The IOP reduced from 29 to 20 mm Hg, however, the extent of schisis and the vision (0.4 Log MAR) did not show any change over the course of follow-up (34 months). The visual field showed only a mild progression.

Discussion

The incidence of peripapillary schisis in normal and glaucoma population is unknown and there is now an increasing awareness of this entity with imaging becoming a common practice. Though the exact pathogenesis is unknown, formation of an acquired pit of the optic nerve (APON) and vitreous traction allowing vitreous/subarachnoid fluid to seep through lamina cribrosa are thought to be the two most plausible explanations.5, 6 Though most of our patients had significant optic disc damage, APON was not clinically evident in any of the eyes. In a previously published study with POAG eyes, APON was visible in only one-third of cases.1 Its absence in two-third of cases in that series and in all of our patients proves that optic nerve damage is not the sole cause in its causation. A recent study in Korean subjects, employing enhanced depth imaging (EDI) of the optic nerve, showed the presence of central/peripheral lamina cribrosa (LC) defects in eyes with peripapillary schisis either due to glaucoma or pachychoroid diseases.7 As EDI was not used as an imaging modality in this study, the possibility of LC defects causing this pathology, cannot be excluded.

Raised IOP and its fluctuation have also been associated with peripapillary schisis occurence.4 The eye with macular involvement had a higher IOP (29 mm Hg), as compared with the mean at the time of schisis detection, though the optic nerve and visual field damage in this eye were much less than the rest of the cohort. Macular schisis is known to develop from vitreous traction near the RNFL defect in glaucomatous eyes.8

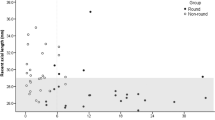

We could not detect any evidence of vitreo-macular traction and this eye has maintained stable vision and fields over the last 34 months of follow-up. IOP reduction is also known to be associated with resolution of the schisis and filtering surgery is rarely indicated.9 Comparable to previously published data,1 40% of our eyes too showed schisis resolution with IOP reduction. Though the numbers are small to detect any statistical change, the mean IOP at resolution (12.2 mm Hg) was much lower than IOP at its detection (18 mm Hg) in these four eyes. We believe that IOP lowering alone is not the sole explanation for schisis resolution as a similar IOP drop in the other six eyes did not have any bearing on its appearance. Interestingly, the visual fields worsened in four eyes (of which three eyes had shown resolution) within 11 months of its detection and we believe that this change is due to glaucoma progression and is not related to the outcome of schisis. Finally, a significant reduction in RNFL thickness was noticeable once the peripapillary schisis resolved (mean 209.2 μ before and 94.5 μ on resolution, P=0.008) and therefore we advise caution when interpreting serial RNFL output data.10

With sparse publications on this subject, our series adds more knowledge to its association in open-angle disease and on its natural history. This is the first series of peripapillary schisis in Caucasian eyes and larger prospective studies with a longer follow-up in normal and glaucoma eyes are needed to ascertain its incidence and natural history.

References

Lee EJ, Kim T-W, Kim M, Choi YJ . Peripapillary schisis in glaucomatous eyes. PLoS One 2014; 9 (2): e90129.

Zhao M, Li X . Macular retinoschisis associated with normal tension glaucoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2011; 249: 1255–1258.

Örnek N, Büyüktortop N, Örnek K . Peripapillary and macular retinoschisis in a patient with pseudoexfoliation glaucoma. BMJ Case Rep. e-pub ahead of print 31 May 2013 doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-009469.

Kahook MY, Noecker RJ, Ishikawa H, Wollstein G, Kagemann L . Peripapillary schisis in glaucoma patients with narrow angles and increased intraocular pressure. Am J Ophthalmol 2007; 143: 697–699.

Georgalas I, Ladas I, Georgopoulos G, Petrou P . Optic disc pit: a review. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2011; 249: 1113–1122.

Imamura Y, Zweifel SA, Fujiwara T, Freund KB, Spaide RF . High resolution optical coherence tomography findings in optic pit maculopathy. Retina 2010; 30: 1104–1112.

Lee JH, Park HL, Baek J, Lee WK . Alterations of the lamina cribrosa are associated with peripapillary retinoschisis in glaucoma and pachychoroid spectrum disease. Ophthalmology 2016; pii S0161-6420 (16): 30501–30502.

Inoue M, Itoh Y, Rii T, Kita Y, Hirotal H, Kunita D, Hirakata A . Macular schisis associated with glaucomatous optic neuropathy in eyes with normal intraocular pressure. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2015; 253 (9): 1447–1456.

Zumbro DS, Jampol LM, Folk JC, Olivier MM, Anderson-Nelson S . Macular schisis and detachment associated with presumed acquired enlarged optic nerve head cups. Am J Ophthalmol 2007; 144: 70–74.

Hwang WH, Kim YY, Kim HK, Sohn YH . Effect of peripapillary retinoschisis on retinal nerve fibre layer thickness measurement in glaucomatous eyes. Br J Ophthalmol 2014; 98 (5): 669–674.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dhingra, N., Manoharan, R., Gill, S. et al. Peripapillary schisis in open-angle glaucoma. Eye 31, 499–502 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.235

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.235

This article is cited by

-

Severe macular complications in glaucoma: high-resolution multimodal imaging characteristics and review of the literature

BMC Ophthalmology (2023)

-

Glaucomatous optic nerve damage in the contralateral eye of a patient with peripapillary retinoschisis: a case report

BMC Ophthalmology (2023)

-

A Response to: Letter to the Editor Regarding “Agreement Between Trend-Based and Qualitative Analysis of the Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness for Glaucoma Progression on Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography”

Ophthalmology and Therapy (2022)

-

Disc hemorrhage following peripapillary retinoschisis in glaucoma: a case report

BMC Ophthalmology (2021)

-

Ocular biometric parameters are associated with non-contact tonometry measured intraocular pressure in non-pathologic myopic patients

International Ophthalmology (2020)