Abstract

Objective:

Maternal overweight/obesity and depression are among the most prevalent pregnancy complications, and although individually they are associated with poor pregnancy outcomes, their combined effects are unknown. Owing to this, the objective of this study was to determine the prevalences and the individual and combined effects of depression and overweight/obesity on neonatal outcomes.

Methods:

A retrospective cohort study of all singleton hospital births at >20 weeks gestation in Ontario, Canada (April 2007 to March 2010) was conducted. The primary outcome measure was a composite neonatal outcome, which included: stillbirth, neonatal death, preterm birth, birth weight <2500 g, <5% or >95%, admission to a neonatal special care unit, or a 5-min Apgar score <7.

Results:

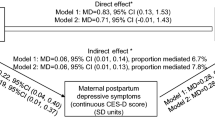

Among the 70 605 included women, 49.7% had a healthy pre-pregnancy BMI, whereas 50.3% were overweight/obese; depression was reported in 5.0% and 6.2%, respectively. Individually, depression and excess pre-pregnancy weight were associated with an increased risk of adverse neonatal outcomes, but the highest risk was seen when they were both present (16% of non-depressed healthy weight pregnant women, 19% of depressed healthy weight women, 20% of non-depressed overweight/obese women and 24% of depressed overweight/obese women). These higher risks of adverse neonatal outcomes persisted after accounting for potential confounding variables, such as maternal age, education and pre-existing health problems (adjusted odds ratio (OR) 1.22, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.13–1.33, adjusted OR 1.23, 95% CI 1.18–1.28 and adjusted OR 1.42, 95% CI 1.31–1.54, in the last three groups above, respectively, relative to non-depressed healthy weight women). There was no significant interaction between weight category and depression (P=0.2956).

Conclusions:

When dually present, maternal overweight/obesity and depression combined have the greatest impact on the risk of adverse neonatal outcomes. Our findings have important public health implications given the exorbitant proportions of both of these risk factors.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Heslehurst N, Ells LJ, Simpson H, Batterham A, Wilkinson J, Summerbell CD . Trends in maternal obesity incidence rates, demographic predictors, and health inequalities in 36,821 women over a 15-year period. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2007; 114: 187–194.

Chereshneva M, Hinkson L, Oteng-Ntim E . The effects of booking body mass index on obstetric and neonatal outcomes in an inner city UK tertiary referral centre. Obstet Med 2008; 1: 88–91.

Scott-Pillai R, Spence D, Cardwell C, Hunter A, Holmes V . The impact of body mass index on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a retrospective study in a UK obstetric population, 2004-2011. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2013; 120: 932–939.

Savitz DA, Dole N, Herring AH, Kaczor D, Murphy J, Siega-Riz AM et al. Should spontaneous and medically indicated preterm births be separated for studying aetiology? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2005; 19: 97–105.

Roman H, Goffinet F, Hulsey TF, Newman R, Robillard PY, Hulsey TC . Maternal body mass index at delivery and risk of caesarean due to dystocia in low risk pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2008; 87: 163–170.

Salihu HM, Lynch O, Alio AP, Liu J . Obesity subtypes and risk of spontaneous versus medically indicated preterm births in singletons and twins. Am J Epidemiol 2008; 168: 13–20.

Chatillon O, Even C . Antepartum depression: prevalence, diagnosis and treatment. Encephale 2010; 36: 443–451.

Molyneaux E, Poston L, Ashurst-Williams S, Howard L . Obesity and mental disorders during pregnancy and postpartum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2014; 123: 857–867.

McDonald SD, Han Z, Mulla S, Beyene J, on behalf of the Knowledge Synthesis Group. Overweight and obesity in mothers and risk of preterm birth and low birth weight infants: a systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ 2010; 341: c3428.

Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, Melville JL, Iyengar S, Katon WJ . A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010; 67: 1012–1024.

Goedhart G, Snijders AC, Hesselink AE, van Poppel MN, Bonsel GJ, Vrijkotte TG . Maternal depressive symptoms in relation to perinatal mortality and morbidity: results from a large multiethnic cohort study. Psychosom Med 2010; 72: 769–776.

Abenhaim HA, Kinch RA, Morin L, Benjamin A, Usher R . Effect of prepregnancy body mass index categories on obstetrical and neonatal outcomes. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2007; 275: 39–43.

Sebire NJ, Jolly M, Harris JP, Wadsworth J, Joffe M, Beard RW et al. Maternal obesity and pregnancy outcome: a study of 287,213 pregnancies in London. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25: 1175–1182.

Kumari AS . Pregnancy outcome in women with morbid obesity. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2001; 73: 101–107.

von EE, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP . The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007; 370: 1453–1457.

Perinatal Partnership Program of Eastern and Southeastern Ontario (PPPESO). Annual Perinatal Statistical Report 2006-07. Accessed 11 July 2011. Available at https://www.nidaydatabase.com/info/pdf/200607 AnnualReportFinal.pdf. Statistics Canada. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. 2007.

The Niday Perinatal Database. Better Outcomes Registry & Network (BORN) Ontario. https://www.nidaydatabase.com 2011.

Dunn S, Bottomley J, Ali A, Walker M . 2008 Niday perinatal database quality audit: report of a quality assurance project. Chronic Dis Inj Can 2011; 32: 32–42.

Postal Code Conversion File (PCCF) 2006 Reference guide. Statistics Canada. Accessed 5 July 2011 http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/92f0153g/92f0153g2007001-eng.pdf 30-1-2007. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada., Statistics Canada. 24-10-2011.

Rubin DB . Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Wiley: New York, 1987.

Little RJA, Rubin DB . Statistical Analysis with Missing Data 2nd edn. Wiley: New York, 2002.

Miller GJ . Lipoproteins and the haemostatic system in atherothrombotic disorders. Baillieres Clin Haematol 1994; 7: 713–732.

Retnakaran R, Hanley AJ, Raif N, Connelly PW, Sermer M, Zinman B . C-reactive protein and gestational diabetes: the central role of maternal obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88: 3507–3512.

Madan JC, Davis JM, Craig WY, Collins M, Allan W, Quinn R et al. Maternal obesity and markers of inflammation in pregnancy. Cytokine 2009; 47: 61–64.

Nohr EA, Bech BH, Vaeth M, Rasmussen KM, Henriksen TB, Olsen J . Obesity, gestational weight gain and preterm birth: a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Paediatr Perinatal Epidemiol 2007; 21: 5–14.

Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim EK et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 67: 446–457.

Rich-Edwards JW, Mohllajee AP, Kleinman K, Hacker MR, Majzoub J, Wright RJ et al. Elevated midpregnancy corticotropin-releasing hormone is associated with prenatal, but not postpartum, maternal depression. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: 1946–1951.

Kammerer M, Taylor A, Glover V . The HPA axis and perinatal depression: a hypothesis. Arch Womens Ment Health 2006; 9: 187–196.

Diego MA, Jones NA, Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C et al. Maternal psychological distress, prenatal cortisol, and fetal weight. Psychosom Med 2006; 68: 747–753.

Stevens AD, Lumbers ER . Effects of intravenous infusions of noradrenaline into the pregnant ewe on uterine blood flow, fetal renal function, and lung liquid flow. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 1995; 73: 202–208.

Nagahawatte NT, Goldenberg RL . Poverty, maternal health, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008; 1136: 80–85.

Norbeck JS, Tilden VP . Life stress, social support, and emotional disequilibrium in complications of pregnancy: a prospective, multivariate study. J Health Soc Behav 1983; 24: 30–46.

Coverdale JH, Chervenak FA, McCullough LB, Bayer T . Ethically justified clinically comprehensive guidelines for the management of the depressed pregnant patient. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996; 174: 169–173.

Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, Lander S . "Are you depressed?" Screening for depression in the terminally ill. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154: 674–676.

Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS . Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med 1997; 12: 439–445.

Gosse MA . How accurate is self-reported BMI? Nutr Bull 2014; 39: 105–114.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Regional Medical Association (RMA) grant, and Sarah D McDonald is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) New Investigator Award # CNl 95357. RMA and CIHR had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McDonald, S., McKinney, B., Foster, G. et al. The combined effects of maternal depression and excess weight on neonatal outcomes. Int J Obes 39, 1033–1040 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2015.44

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2015.44

This article is cited by

-

Depression, obesity and their comorbidity during pregnancy: effects on the offspring’s mental and physical health

Molecular Psychiatry (2021)

-

Maternal body mass index moderates antenatal depression effects on infant birthweight

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Antenatal and postnatal depression in women with obesity: a systematic review

Archives of Women's Mental Health (2017)

-

Time trends and risk factor associated with premature birth and infants deaths due to prematurity in Hubei Province, China from 2001 to 2012

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2015)

-

Pregnancy complications associated with the co-prevalence of excess maternal weight and depression

International Journal of Obesity (2015)