Abstract

Background:

In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the problem of poor patient participation in studies of self-management (SM) and pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) programmes (together referred to as COPD support programmes) is established. Understanding this problem beyond the previously reported socio-demographics and clinical factors is critical.

Aims:

The aim of this study was to explore factors that explain patient participation in studies of COPD support programmes.

Methods:

Thematic ‘framework’ synthesis was conducted on literature published from 1984 to 1 February 2015. Emergent themes and subthemes were mapped onto the adapted ‘attitude–social influence–external barriers’ and the ‘self-regulation’ models to produce analytical themes.

Results:

Ten out of 12 studies were included: PR (n=9) and SM (n=1). Three descriptive themes with 38 subthemes were mapped onto the models' constructs, and it generated four analytical themes: ‘attitude’, ‘social influences’ and ‘illness’ and ‘intervention representations’. The following factors influenced (1) attendance—helping oneself through health improvements, perceived control of worsening condition, perceived benefits and positive past experience of the programme, as well as perceived positive influence of professionals; (2) non-attendance—perceived negative effects and negative past experience of the programme, perceived physical/practical concerns related to attendance, perceived severity of condition/symptoms and perceived negative influence of professionals/friends; (3) dropout—no health improvements perceived after attending a few sessions of the programme, perceived severity of the condition and perceived physical/practical concerns related to attendance.

Conclusions:

Psychosocial factors including perceived practical/physical concerns related to attendance influenced patients’ participation in COPD support programmes. Addressing the negative beliefs/perceptions via behaviour change interventions may help improve participation in COPD support programmes and, ultimately, patient outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Programmes such as pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) and self-management (SM) education programmes that support patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), to increase their skills and confidence to better self-manage their condition, are established treatments alongside pharmacological treatment.1–4 However, studies of these programmes report poor patient participation and high dropout rates,5–7 with similar problems acknowledged in clinical practice.8 Understanding the problem of poor patient participation and retention is therefore critical9 before strategies to improve participation can be suggested.

Our recent review10 highlighted that ‘participation’ is a term used differently by different researchers. Here, by ‘participation’ we mean ‘taking part in a study or intervention’ with ‘attendance’, ‘non-attendance’ and ‘dropout’, all aspects of participation—where attendance means ‘exposed to at least part of the intervention’; non-attendance means ‘exposed to no part of the intervention’; dropout means ‘dropped out from the intervention’; completion means ‘completing the study or intervention’.

A mixed-methods review11 of participation in PR programmes attributed patient non-attendance and dropout to personal, clinical, social and physical barriers. Only one study12 of a COPD SM programme has explored reasons for high or low attendance, and the findings comprised a mix of socio-demographic, personal and clinical factors. It has been suggested that socio-demographic and clinical factors may be insufficient to understand the problem of poor participation in these programmes; a new approach is therefore needed.6,8,13

We propose that an approach that views participation as a health behaviour and that uses health behaviour theory and constructs related to behaviour change could further our understanding of participation behaviour.14 Such an approach could help identify appropriate targets for an intervention,13 with the ultimate aim of improving patient participation in PR and COPD SM programmes, thus enhancing patient outcomes.

Health behaviour theory has been used in several studies15–23 to explain or predict participation, particularly attendance in patients with a variety of conditions; however, only one study20 has used such an approach in COPD.

The aim of this qualitative synthesis was to explore the factors that might explain patient participation in studies of COPD SM and PR programmes. PR, including provision of individually prescribed lower limb exercise training,24 encourages and assists patient SM by promoting decision-making and self-efficacy through SM education in goal setting and setting an action plan.3 SM education is integral to the delivery of SM programmes.7 Hence, these will be together referred to here as COPD support programmes. The research questions were as follows:

-

1)

What are the possible factors affecting patient participation in COPD support programmes?

-

2)

Can behavioural theory help explain patient participation in COPD support programmes?

Materials and methods

The qualitative synthesis sat within a broader review of participation,10 which followed recommended guidance for conducting systematic reviews;25 one search strategy was applied to identify both qualitative and quantitative studies (Supplementary Appendix 1). All qualitative research studies from 1984 to 1 February 2015, exploring reasons for participation in studies of PR, SM and health education programmes, including in the programme, by patients with COPD were considered for inclusion. We included studies that explored patient reasons for not attending their initial PR assessment and patient views of participation before the start of the programme.

Data extraction (Supplementary Appendix 1) included findings of each primary study.26 We used the modified critical appraisal skills programme checklist27 for quality assessment.

Thematic ‘framework’ synthesis, an established method, was conducted.26 The synthesis involved three distinct stages.26,28,29

-

1)

The findings of each included study were coded to generate free concepts with review questions in mind. The emergent concepts from one study were compared with those from other included studies, which was referred to as the translation of concepts.

-

2)

The emergent concepts were examined for similarities and differences, and then grouped and placed under new codes that captured the meaning of the grouped concepts to produce ‘descriptive themes’ and subthemes.

-

3)

These descriptive themes and subthemes were ‘mapped’ onto two a priori theoretical models with subsequent ‘generation of analytical themes’ that went beyond the findings of the original studies. An a priori ‘framework’, characteristic to framework synthesis, is informed from the literature and team discussion to synthesise findings.28 We applied the recommended ‘best fit’ framework synthesis approach,29,30 whereby an existing conceptual model, which most closely matches the research topic under study, is used to carry out the synthesis. Using the ‘best fit’ approach helped us in limiting our selection among the numerous and varied behaviour change theories to identifying two most applicable health behaviour theories, as they had previously been used in studies to explain participation behaviour of patients with chronic disease in SM support programmes. We used the adapted ‘attitude–social influence–external barriers’ model that has previously been used to explain intention to participate in an asthma SM programme16 and the ‘self-regulation’ model that has been used to explain cardiac rehabilitation utilisation21 and examined whether our results were consistent with either or both these models. Figure 1 briefly describes these two models and Supplementary Appendix 2 elaborates on the models.

Figure 1 The ‘best fit’ theoretical models. The adapted ‘attitude–social influence–external barriers' model. Lemaigre et al.16 reported using the ‘attitude–social influence–self-efficacy’ model by de Vries et al. to explain intention to participate in an asthma self-management programme. The constructs as measured by Lemaigre were as follows: attitude including personal and general benefits of the asthma programme. Social influence including social norms to take care of their asthma and motivation to comply with these. Self-efficacy (external barriers) including beliefs about barriers to participate. It should be noted that the definitions of these constructs vary slightly from those used in the original de Vries model (see Supplementary Appendix 2 for further details), particularly that of self-efficacy, which focuses primarily on external barriers and hence is labelled as such here. The figure above illustrates the distal, proximal socio-cognitive and external constructs of the adapted model that explained intention to participate in an asthma self-management programme in the study by Lemaigre et al.16 The descriptive themes and subthemes were ‘mapped’ onto the adapted model’s theoretical constructs. The ‘self-regulation’ model. Keib et al.21 used the ‘self-regulation model’ by Leventhal et al. and the ‘necessity-concerns framework’ by Horne to explain participation in cardiac rehabilitation among patients with coronary heart disease. The self-regulation model explains the effort an individual makes, in response to a health threat, to protect and maintain health and to avoid and control illness based on representations of the illness. The threats (physical and psychological indicators) that disrupt physical and cognitive function as a result of the illness make contributions to the illness representation. Leventhal et al. in the 1990s stated the five domains of ‘illness representations’: 'disease identity' is the perceived symptom experienced as a result of an illness and the symptoms associated with the illness. 'Timeline' is the perceived expected duration of illness (acute and chronic) or expected age of onset of illness. 'Consequences' is the perceived severity and impact on life functions as a result of the illness. Cause could be perceived as internal (e.g., genes) or external (e.g., infection). Control/cure is whether the illness is perceived as ‘preventable’, ‘curable’ or ‘controllable’. These illness representations can lead an individual to generate goals, and to develop and carry out action plans (referred to as coping procedures), which are subsequently evaluated in relation to whether the threat has been eliminated or controlled and influence subsequent representations of the illness and behaviour and hence self-regulation. Horne within the ‘necessity-concerns framework’ stated that 'necessity' beliefs are perceived personal needs for the treatment and 'concerns' beliefs are perceived concerns of the treatment, both of which influence treatment adherence. The figure above illustrates the illness and treatment representations that explained participation in cardiac rehabilitation in the study by Keib et al.21 The descriptive themes and subthemes were ‘mapped’ onto the above-mentioned theoretical constructs. Supplementary Appendix 1 describes how Keib used the model to explain participation.

Results

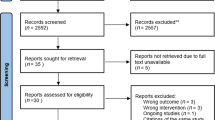

Ten studies were included in this review (Figure 2).31 Two studies32,33 were excluded because patients’ reasons for participation were not explored. Nine of the included studies examined PR programmes,11,34–41 and only one study examined a COPD SM programme.12 Table 1 presents the study characteristics.

PRISMA flowchart.31

Quality appraisal

The agreement between the authors on the modified critical appraisal skills programme checklist score was 100%. There was variation in study reporting—e.g., lack of clear reporting on sampling strategy,34–36 the data analysis process,37 the research questions36 and in some cases the authors’ interpretation of data was not supported with verbatim data.35,36,38,40 The level of agreement, for mapping of subthemes onto a priori theory, was higher for the adapted ‘attitude–social influence–external barriers’ model (97%) compared with the ‘self-regulation’ model (88%).

Synthesis findings

The synthesis generated three descriptive themes (with 38 subthemes (Table 2)) related to reasons or potential reasons for:

-

1)

Attending SM and PR programmes and reasons for continuing and completing PR,

-

2)

Not attending SM and PR programmes and

-

3)

Dropping out of SM and PR programmes.

Twenty-nine subthemes were mapped onto both theoretical models; four subthemes were not mapped onto the adapted model and five were not mapped to the ‘self-regulation’ model either owing to limited primary data or lack of correspondence to model constructs. In some cases, subthemes were mapped onto more than one theoretical construct within the same model (Table 3). In addition, overlap between different model constructs was observed (Table 3); for instance, the same subthemes that were mapped onto the ‘attitude’ construct of the adapted ‘attitude–social influence–external barriers’ model were also mapped onto the ‘intervention representations’ construct of the ‘self-regulation’ model.

The mapping revealed four key behavioural constructs that formed our analytical themes and explained the three descriptive themes of participation (attendance, non-attendance and dropout) in COPD SM support. In the adapted ‘attitude–social influence–external barriers’ model, patient socio-demographics or perception of clinical symptoms contributed to the formation of beliefs about participation in COPD support programmes, and these beliefs were captured by the ‘attitude’ and ‘social influences’ construct of the model. While in the ‘self-regulation’ model, the perceived health threat (COPD) along with the personal illness experience and the medical and social communication led to the formation of perceptions about the illness and the intervention (COPD support programmes) which led to participation; these perceptions were captured by the ‘illness representations’ and ‘intervention representations’ constructs of the model. These findings went beyond the findings of the included primary studies. The analytical themes are described below. Figure 3 illustrates the behavioural factors that can affect participation behaviour.

Attitude

The attitude of attenders was that COPD support programmes12,34–36 could help improve their health and condition. Many participants wanted to help themselves34,41 and wanted to learn about their condition.12 Some participants wanted to gain control of their condition.34–36,39 A few wanted to cope with the illness and remain independent.36,39 Besides perceived health benefits, social benefits were important too.12,34 Some participants saw COPD support programmes12,34 as a reason to get out of the house, to socialise and meet others with the same illness. Two interviewees reported attending the SM programme for altruistic reasons.12

In the studies by Arnold et al.34 and Guo and Bruce,41 the findings were sub-divided into reasons for ‘attending’ or ‘continuing and completing’ PR (Table 2); a key reason given for continuing and completing PR was social benefits and health benefits including those that were seen immediately following application of skills learnt in PR. Only Fischer et al.35 compared reasons for attending PR in brand new referrals and those who had previously attended the programme. Among the previous attendees, positive past experience of PR, particularly staff supervision and support, influenced attendance. A few patients in the study by Bulley39 had a negative PR experience; however, this did not stop them from having a positive attitude to attending PR again.

In contrast, the attitude among non-attenders was that PR was not beneficial, particularly that the exercise component would not improve health or could not improve health.11,38,40 Several participants in Taylor’s study38 were more interested in research testing new drug treatments and not exercise. Some participants in the same study chose not to attend PR because they perceived the exercise negatively, such as too vigorous, strenuous and detrimental to their health. The majority of participants in the study by Guo41 believed that exercise would make them become breathless. Furthermore, among some interviewees, personal negative experience with exercise in the past such as embarrassment, panic, lack of control and negative research experience led to negative attitudes and were other reasons suggested for PR non-attendance.38,39

With regard to dropout, some participants11,37 dropped out because they did not perceive any health improvements after attending between one and four PR sessions, and therefore they had the attitude that PR was not beneficial. Failing to notice any improvements in health halfway through the programme was also suggested as a potential dropout reason in the study by Fischer et al.35 (Table 2). Other potential dropout reasons suggested in the study by Fischer et al.35 were as follows: inability to keep up with the intensity of the programme and feeling uncomfortable while training with other participants. In two other studies11,40 a few participants dropped out because they were too tired to complete the programme or did not believe that they could continue with the exercises despite being told what to expect.

Social influences

Non-attendance in PR was influenced by a lack of positive feedback or a lack of explanation given on the benefits of the programme. Several participants decided not to attend PR because their friends or family either had not found or they did not think PR would be useful.38 Another trusted source, health professionals, being unable to explain or advise participants about the benefits of PR or not giving any information on what the programme might entail was associated with non-attendance.11,34,35,40

Conversely, the majority of attenders34,35,37 attended PR because their doctor was enthusiastic about the referral and thus they believed that the programme would be useful, they were explained how the programme could benefit them or they simply trusted the advice or suggestion to attend the programme. A referral to PR was enough for some participants to attend PR.39,40

Intervention representations

A positive perception/representation of COPD support programmes influenced attendance. Some participants perceived that the SM programme would help them learn about SM.12 PR was perceived as a positive step to help oneself; participants believed that attending PR would help them gain control of their condition.34–36,39 A few participants saw PR as their only hope of coping with the disease and remaining independent.36,39 Perceived benefits from PR attendance in the past also influenced attendance,35 and for a few participants the negative experience did not deter them from wanting to attend PR again.39 In addition, almost all attenders in the study by Fischer et al.35 perceived PR as a necessity if they wanted to see improvements in their health and were not concerned about their conflicting obligations.

In contrast, the perceived negative effects of exercise/PR11,38,40,41 and previous negative experience with exercise in the past influenced non-attendance among several participants.38,39 Non-attendance in COPD support programmes was also influenced by participants’ perceived environmental concerns related to attendance, such as a complex journey that involved using more than one bus to get to the venue,40 unable to access a car or public transport11 or difficulty in using public transport or parking, particularly for people with restricted mobility, who were housebound/wheelchair bound or relied on gait aids;11,12,35,37,38 location (hospital) of the programme;38,40,41 seasonal weather;38 practical issues such as personal/professional commitments.11,12,35,37,38,40 A few participants indicated that the PR was held too early in the day, and this also affected attendance.11

Some patients dropped out of PR because they expected to see health improvements after only a few sessions.11,37 Some patients dropped out because they felt too tired to complete the programme; a few patients perceived that they would get tired11 or they would be unable to continue with the exercises despite being told what to expect.40 Similar to non-attenders, dropouts were also concerned about issues of access,11,35 including the cost of relying on taxis or of parking, the programme being held too early in the day and competing demands.11,40 In addition, not perceiving any benefits when one was halfway through the programme, an intensive programme and being uncomfortable while training with others in the group were cited as potential dropout reasons.35

Illness representations

The perceived increased severity of condition and its perceived consequences such as effect on ability to cope/self-manage, partake in social activities, be in control and remain independent prompted attendance by several participants in COPD support programmes.12,34–36,40,41

Among non-attenders, some participants felt that they were too disabled to carry out any sort of activity either because of COPD or other co-morbidities37,39,40 or to leave the house without support;12 some felt that their health needed to improve to enable them to attend;11,41 some perceived that improvements in their health were no longer possible;38,41 some feared that their existing condition/s was getting worse.11,35 Conversely, some participants did not perceive their health or condition to be poor or serious enough to warrant attendance.34,38,40

The perceived severity of symptoms also influenced patient dropout behaviour. Suffering an acute exacerbation of COPD or other conditions often led participants to drop out of PR, as they needed time to recover.11,37,41 A couple of participants dropped out of the SM programme because of depression associated with their condition.12 Conversely, a couple of participants in the latter study dropped out because they did not perceive themselves to be physically or psychologically affected by their condition.

Discussion

Main findings

The thematic ‘framework’ synthesis with the use of health behaviour theory helped in gaining an insight into the participation (attendance, non-attendance and dropout) behaviour of patients in COPD support programmes beyond the previously reported socio-demographic and clinical factors. The mapped subthemes yielded higher-order constructs, whereby participation was influenced by an individual’s attitude and perceived social influences, as well as intervention and illness representations.

Attitudes of wanting to help themselves, the perceived influence of health professionals that the programme might bring health improvements, perceptions of the controllability of illness and gaining independence and perceived positive benefits of the COPD support programmes, including past experiences, influenced attendance behaviour. Non-attendance was influenced by a negative attitude that health improvements were no longer or could not be possible, negative perceptions that exercise would not benefit the condition, and past experiences such as perceived physical/practical concerns related to attendance, a lack of information about the programme from professionals, and the negativity of professionals and family/friends towards the programme. Dropout behaviour was influenced by unmet expectations after attending only a few sessions of the programme, perceived severity of symptoms and perceived physical/practical concerns related to attendance.

Interpretation of findings in relation to previously published work

In agreement with studies that have utilised the ‘self-regulation model’ to predict or explain patient participation in rehabilitation among patients with chronic disease including COPD,15,18,20,21 attendance was associated with patients’ perceptions in self to control, gain independence and cope with their condition, and patients' perception of the COPD support programme was perceived as necessary to help control and improve their condition. The same was explained by patients having a positive ‘attitude’ towards the programme in this review and among other studies that have used the adapted ‘attitude–social influence–external barriers’ model16 and the theory of planned behaviour42 to explain patient participation in the asthma SM programme16 and cardiac rehabilitation.42 However, the lack of perceived benefits from attending PR was reported among non-attenders in this study, and it has been reported elsewhere for patients with chronic disease in rehabilitation programmes.15,21,42,43

In addition, we found that a positive past experience with exercise influenced attendance and completion of PR and negative experiences with exercise in the past influenced non-attendance. Within a behavioural context, the benefits gained from previous experience may have led to the formation of positive beliefs about PR, and these beliefs contributed to the appraisal of ‘attending’ PR as positive. The positive appraisal was retrieved44 after invitation to attend PR, which might have led to attendance. Conversely, the reverse could have resulted in non-attendance. However, for two participants in this study a past negative experience of PR did not prevent them from wanting to attend PR again. This has been explained by the participants having a positive attitude towards the programme and a result of having positive interactions with health-care professionals.39

A referral to PR, and in addition referral from enthusiastic health-care professionals who gave advice, suggestions or explanations on how the programme might benefit health or their condition, influenced many patients to attend PR in this review. In contrast, patients who did not remember the referral and professionals who provided no explanation on how the programme could help the patient or used words such as ‘intensive’ or ‘there’s nothing we can do for you’, or family and friends who associated the programme as a ‘waste of time’, were negative influences, and this led to patient non-attendance. Patients with COPD have faith in their health professionals,39 and studies16,42 have shown that rehabilitation attenders strongly believed that their doctor, family or friend wanted them to attend rehabilitation. This suggests that to enable programme attendance, professionals, family and friends should work together or initiate a ‘dialogue’ with a patient, identify their needs45 and accordingly advise on programme benefits that other patients might have experienced, such as social and psychological benefits,43 improvements in activities of daily living,46 self-esteem and self-worth,46 and strength, balance and flexibility.47 Recently, advice or individual counselling from trained health-care professionals in primary care settings that include behaviour change strategies, such as establishing objectives and writing physical activity prescriptions, have been reported as most effective in promoting, changing or increasing health behaviours.48,49 Perhaps these strategies could also be applied to improve attendance behaviour in COPD support programmes. Advice about PR benefits through peer support has also been recommended in studies to increase programme attendance.11,40 This latter form of support may particularly help improve PR adherence among people who live alone and require encouragement and confidence to continue their attendance, which was found in this study.

Non-attendance and non-completion has previously been explained in terms of the value ascribed to PR, minimal value or low relative value in view of other more important values, burdens and costs are reported among non-attenders and high relative value among non-completers who may be more likely to consider attending PR if other values or burdens could be addressed.11 Behaviourally, we were able to explain this another way, whereby some attenders perceived COPD support programmes as necessary to attend, as they were clear on its benefit and were not concerned about the practical/physical barriers related to attendance. In contrast, some non-attenders were unclear or did not believe in the benefits of exercise for their health, and non-completers did not perceive health improvements after attending one to four sessions (of a twice weekly, 6–12-week programme),24 and both non-attenders and non-completers perceived several practical/physical concerns related to attendance. By assessing, eliciting and understanding patient perceptions about COPD support programmes, we might be able to identify patients who could be targeted by behaviour change interventions aimed to improve programme uptake19 such as changing or challenging patients’ beliefs and misconceptions3,50 before programme attendance3 and having physical/practical resources50 in place to enable participation—e.g., programme commissioners could plan for payment of patient transport, thereby helping to reduce the burden of travel and costs from the patient.24 Home-based services or PR have been suggested by studies11,40 based on patient preference for PR completion; however, this alternative should not be aimed at patients with low motivation or low interest,51 which could be determined during patient assessment.

Some patients in this review dropped out of PR after a few sessions because of unmet expectations in terms of health improvements, which could be because they might not have been told what to expect from PR;52 however, the intensity of the programme was another reason that led some patients to drop out despite them being told what to expect from the programme before attendance. This suggests that perhaps the PR staff could follow-up patients after the end of the first few sessions to identify any patient issues or concerns related to exercise/programme and attendance.19 Here again negative beliefs might need targeting using behaviour change interventions19,50 or more resources might be needed—e.g., more staff for supervision of patients who might be more disabled or in need of more attention.24 The support offered by PR or structured exercise programme staff has been deemed important for completion of the programme by patients with chronic disease43 and older people.47 A recent study53 to maintain adherence in a hospital-based smoking cessation service evaluated a booklet that presented information about the effectiveness of the service (presented smoking cessation rates of the service alongside those achieved nationwide) and asked participants to read and tick pre-defined implementation intentions (or ‘if-then’ plans) and found that the booklet improved adherence but not the intention implementation plans. The authors attributed this to patients’ high socio-economic status and reading and ticking pre-designed ‘if-then’ statements rather than forming individualised plans that are associated with behaviour change. COPD is a disease mostly associated with people belonging to low socio-economic status54 and they are widely reported to have poor literacy and health literacy.55 As a result, trained staff working with patients in partnership to develop understanding of benefits and develop tailored ‘if-then’ implementation plans before programme attendance may help to improve participation in COPD support programmes.

Finally, we found that while perceived severity of the condition or symptoms influenced patient attendance in COPD support programmes also reported elsewhere,18 the perceived severity of symptoms and lack of the fear of symptoms getting worse or not yet having recovered mentally or physically owing to previous exacerbation of COPD or other conditions led to patient non-attendance and dropout in this study. The perception of less severity of symptoms has been reported previously among non-attenders in cardiac rehabilitation.56 Patient participation might improve if patients who perceive severity of symptoms can be reassured using either a theoretically worded letter57 or explained in person about the aim of COPD support programmes, the immediate benefits that they might be able to see41 or shown by invitation to attend a trial session.58 In addition, patients should be given enough time and space to recover from their exacerbation, and readiness to attend should be assessed and addressed followed by appropriate referrals to help improve patient participation.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A strength of this study is that it is the first qualitative systematic review to include 10 qualitative primary studies that aimed to understand patients’ views on each aspect of participation behaviour in COPD support programmes. Previously, a mixed-methods review that explored PR non-attendance and non-completion had included five studies,5 three of which were included in this study. However, because of limited resources, only papers in the English language were included in the review. Only one study of a COPD SM programme was included in the review; hence, the findings unique to PR and SM programmes have been specified throughout to make it clear to readers. The included studies were not underpinned by the health behaviour theory; however, this qualitative synthesis with application of two theories to the studies’ findings has made a contribution towards understanding the cognitions that may influence attendance, non-attendance and non-completion behaviour, and has helped to identify key behavioural constructs that can be targeted to improve patient participation.

Some aspects of method reporting were insufficient in some studies—e.g., limited verbatim data. This could affect the transferability of the findings in practice.59 However, the study participants were the right people to answer the research questions,60 and in line with the review aim we were able to identify a breadth of reasons given for each aspect of participation in COPD support programmes. The inadequate data also prevented mapping of a few subthemes onto the behavioural models constructs.

Both the ‘best fit’ theoretical models were able to explain patient participation to a considerable extent, and our review findings were consistent with both these models. However, at times it was challenging to map an individual’s view or beliefs into the distinct theoretical cognitive constructs; e.g., a reason given for participation was mapped onto more than one construct of the same framework. This suggests that an individual’s cognitions are interlinked and help inform an individual’s decision-making to perform certain behaviour.61 In addition, using the ‘best fit’ approach described by Carroll et al.29 limited us to some extent, whereby we used theories previously utilised in studies and not the newer/latest model versions.62,63

Implications for future research, policy and practice

The study findings have implications for improving participation in COPD support programmes including other interventions aimed at chronic disease patients.

In practice, the findings help in understanding that patient beliefs or perceptions of their illness, the COPD support programmes including the physical and practical concerns related to patient attendance, and social influences, can lead to programme attendance, non-attendance, or dropout behaviour. These findings could also be applicable to other interventions such as cardiac rehabilitation, SM training, physical activity/exercise, smoking cessation that also experience poor attendance and completion by patients with chronic disease other than COPD.18,64,65 For professionals involved in caring for patients with chronic disease, it highlights the importance of patient engagement66 and prioritising discussion about their illness and its treatment67 for improving motivation and longer-term participation in the treatment.19 During patient engagement, it would be important for health-care professionals to explain the benefits of the programme in relation to the outcome/s patients would like to achieve for themselves, including the benefits that could be expected straightaway after attending a few sessions and in the longer term. Provision of encouragement and reassurance to patients that the programme can help them learn strategies to gain control, cope and remain independent is critical alongside organisation of smoother referrals68 and travel arrangements for improvement in patient participation. To help facilitate this, professionals will require provision of training and support,69 increasing availability of programmes in areas local to patients and creating awareness and better communication about service provision.70

Assessment of patient perceptions during routine consultations has been suggested for COPD.71,72 We propose adaptation of the illness perception63 and intervention perception questionnaire19 commonly used in studies to predict attendance in cardiac rehabilitation. Assessment of patient perceptions will help identify eligible and suitable patients for the treatment and predict attendance in the treatment.19 In addition, the negative perceptions towards illness and treatment73 could be targeted using effective behaviour change interventions48,53,57 to help improve participation in COPD support programmes. To get health professionals and indeed the wider health system to ‘buy-in’ this form of patient support, exploring the views of professionals (beyond factors affecting patient referral or perceived patient challenges in attending PR68,74) is warranted.

Conclusions

This qualitative synthesis with application of the health behaviour theory is to our knowledge the first to explore the full range of patient participation behaviour in SM support programmes among patients with COPD, and it has helped explain participation beyond the previously reported socio-demographic and clinical factors. The synthesis helped identify a list of reasons that explained patient participation, and application of theory helped to understand that participation behaviour was influenced by a participant’s attitude and perceived social influences and their perceptions towards the illness and the intervention. As these psychosocial constructs are amenable to change,18,44 targeting these key constructs may help improve participation in COPD support programmes and improve health outcomes.

References

Jones R, Gruffydd-Jones K, Pinnock H, Peffers SJ, Lawrence J, Scullion J et al. Summary of the consultation on a strategy for services for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in England. Prim Care Respir J 2010; 19 Suppl 2: S1–S17.

Labrecque M, Rabhi K, Laurin C, Favreau H, Moullec G, Lavoie K et al. Can a self-management education program for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease improve quality of life? Can Respir J 2011; 18: e77–e81.

Bolton CE, Bevan-Smith EF, Blakey JD, Crowe P, Elkin SL, Garrod R et al. British Thoracic Society guideline on pulmonary rehabilitation in adults. Thorax 2013; 68: ii1–ii30.

Effing TW, Bourbeau J, Vercoulen J, Apter AJ, Coultas D, Meek P et al. Self-management programmes for COPD: moving forward. Chron Respir Dis 2012; 9: 27–35.

Keating A, Lee A, Holland AE . What prevents people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from attending pulmonary rehabilitation? A systematic review. Chron Respir Dis 2011; 8: 89–99.

Smith SM, Partridge MR . Getting the rehabilitation message across: emerging barriers and positive health benefits. Eur Respir J 2009; 34: 2–4.

Taylor S, Sohanpal R, Bremner S, Devine A, McDaid D, Fernandez J-L et al. Self-management support for moderate-to-severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract 2012; 62: e687–e695.

Hogg L, Garrod R, Thornton H, McDonnell L, Bellas H, White P . Effectiveness, attendance, and completion of an integrated, system-wide pulmonary rehabilitation service for COPD: prospective observational study. COPD 2012; 9: 546–554.

Nici L, ZuWallack R . An Official American Thoracic Society workshop report: the integrated care of the COPD patient. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2012; 9: 9–18.

Sohanpal R, Hooper R, Hames R, Priebe S, Taylor S . Reporting participation rates in studies of non-pharmacological interventions for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. Syst Rev 2012; 1: 66.

Keating A, Lee AL, Holland AE . Lack of perceived benefit and inadequate transport influence uptake and completion of pulmonary rehabilitation in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Physiother 2011; 57: 183–190.

Sohanpal R, Seale C, Taylor SJ . Learning to manage COPD: a qualitative study of reasons for attending and not attending a COPD-specific self-management programme. Chron Respir Dis 2012; 9: 163–174.

Michie S, Prestwich A . Are interventions theory-based? Development of a theory coding scheme. Health Psychol 2010; 29: 1–8.

Hagger MS . What makes a 'good' review article? Some reflections and recommendations. Health Psychol Rev 2012; 6: 141–146.

Cooper A, Jackson G, Weinman J, Horne R . A qualitative study investigating patients' beliefs about cardiac rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil 2005; 19: 87–96.

Lemaigre V, Van den BO, Van HK, De PS, Victoir A, Verleden G . Understanding participation in an asthma self-management program. Chest 2005; 128: 3133–3139.

Helitzer DL, Peterson AB, Sanders M, Thompson J . Relationship of stages of change to attendance in a diabetes prevention program. Am J Health Promot 2007; 21: 517–520.

French DP, Cooper A, Weinman J . Illness perceptions predict attendance at cardiac rehabilitation following acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res 2006; 61: 757–767.

Cooper A, Weinman J, Hankins M, Jackson G, Horne R . Assessing patients' beliefs about cardiac rehabilitation as a basis for predicting attendance after acute myocardial infarction. Heart 2007; 93: 53–58.

Fischer MJ, Scharloo M, Abbink JJ, Hul AJ, van Ranst D, Rudolphus A et al. Drop-out and attendance in pulmonary rehabilitation: The role of clinical and psychosocial variables. Respir Med 2009; 103: 1564–1571.

Keib CN, Reynolds NR, Ahijevych KL . Poor use of cardiac rehabilitation among older adults: A self-regulatory model for tailored interventions. Heart Lung 2010; 39: 504–511.

Toth-Capelli KM, Brawer R, Plumb J, Daskalakis C . Stage of change and other predictors of participant retention in a behavioral weight management program in primary care. Health Promot Pract 2013; 14: 441–450.

Blair J, Angus NJ, Lauder WJ, Atherton I, Evans J, Leslie SJ . The influence of non-modifiable illness perceptions on attendance at cardiac rehabilitation. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2013; 13: 55–62.

British Thoracic Society and Primary Care Respiratory Society UK. IMPRESS Guide to Pulmonary Rehabilitation. British Thoracic Society and Primary Care Respiratory Society: London, UK, 2011, p. 3.

Systematic Reviews CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care . Available at: www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/pdf/Systematic_Reviews.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2010).

Thomas J, Harden A . Methods for the thematic systhesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008; 8: 45.

Campbell R, Pound P, Pope C, Britten N, Pill R, Myfanwy M et al. Evaluating meta-ethnography: a synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Soc Sci Med 2003; 56: 671–684.

Barnett-Page E, Thomas J . Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009; 9: 59.

Carroll C, Booth A, Cooper K . A worked example of ‘best fit’ framework synthesis: a systematic review of views concerning the taking of some potential chemopreventive agents. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011; 11: 29.

Carroll C, Booth A, Leaviss J, Rick J . ‘Best fit’ framework synthesis: refining the method. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013; 13: 37.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG . The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLos Med 2009; 6: e1000097, doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Chen KH, Chen ML, Lee S, Cho HY, Weng LC . Self-management behaviours for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs 2008; 64: 595–604.

Halding A, Wahl A, Heggdal K . 'Belonging'. 'Patients' experiences of social relationships during pulmonary rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil 2010; 32: 1272–1281.

Arnold E, Bruton A, Ellis-Hill C . Adherence to pulmonary rehabilitation: a qualitative study. Respir Med 2006; 100: 1716–1723.

Fischer MJ, Scharloo M, Abbink JJ, Thijs-Van Nies A, Rudolphus A, Snoei L et al. Participation and drop-out in pulmonary rehabilitation: a qualitative analysis of the patient's perspective. Clin Rehabil 2007; 21: 212–221.

Denn D . Patient experiences of pulmonary rehabilitation. Nurs Times 2008; 104.

Gysels MH, Higginson IJ . Self-management for breathlessness in COPD: the role of pulmonary rehabilitation. Chron Respir Dis 2009; 6: 133–140.

Taylor R, Dawson S, Roberts N, Sridhar M, Partridge MR . Why do patients decline to take part in a research project involving pulmonary rehabilitation? Respir Med 2007; 101: 1942–1946.

Bulley C, Donaghy M, Howden S, Salisbury L, Whiteford S, Mackay E . A prospective qualitative exploration of views about attending pulmonary rehabilitation. Physiother Res Int 2009; 14: 181–192.

Moore L, Hogg L, White P . Acceptability and feasibility of pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD: a community qualitative study. Prim Care Respir J 2012; 21: 419–424.

Guo S-E, Bruce A . Improving understanding of and adherence to pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD: a qualitative inquiry of patient and health professional perspectives. PloS One 2014; 9: e110835.

Wyer S, Joseph S, Earll L . Predicting attendance at cardiac rehabilitation: a review and recommendations. Coronary Health Care 2001; 5: 171–177.

Pentecost C, Taket A . Understanding exercise uptake and adherence for people with chronic conditions: a new model demonstrating the importance of exercise identity, benefits of attending and support. Health Educ Res 2011; 26: 908–922.

Conner M, Sparks P. Theory of planned behaviour and health behaviour. In: Conner M, Norman P (eds). Predicting Health Behaviour, 2nd edn. Open University Press: Berkshire, UK, 2005, 170–222.

Ingadottir TS, Jonsdottir H . Partnership-based nursing practice for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and their families: influences on health-related quality of life and hospital admissions. J Clin Nurs 2010; 19: 2795–2805.

Thorpe O, Kumar S, Johnston K . Barriers to and enablers of physical activity in patients with COPD following a hospital admission: a qualitative study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2014; 9: 115–128.

Franco MR, Tong A, Howard K, Sherrington C, Ferreira PH, Pinto RZ et al. Older people's perspectives on participation in physical activity: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative literature. Br J Sports Med 2015, pii: bjsports-2014-094015. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-094015.

Sanchez A, Bully P, Martinez C, Grandes G . Effectiveness of physical activity promotion interventions in primary care: a review of reviews. Prev Med 2014; 76: S56–S67.

Jepson RG, Harris FM, Platt S, Tannahill C . The effectiveness of interventions to change six health behaviours: a review of reviews. BMC Public Health 2010; 10: 538.

Hirani SP, Newman SP . Patients' beliefs about their cardiovascular disease. Heart 2005; 91: 1235–1239.

Beswick A, Rees K, Griebsch I, Taylor F, Burke M, West R et al. Provision, uptake and cost of cardiac rehabilitation programmes: improving services to under-represented group. Health Technol Assess 2004; 8: iii–iv, ix–x, 1–152.

Sully J-L, Baltzman MA, Wolkove N, Demers L . development of a patient needs assessment model for pulmonary rehabilitation. Qual Health Res 2012; 22: 76–88.

Matcham F, McNally L, Vogt F . A pilot randomized controlled trial to increase smoking cessation by maintaining National Health Service Stop Smoking Service attendance. Br J Health Psychol 2014; 19: 795–809.

Prescott E, Vestbo J . Socioeconomic status and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1999; 54: 737–741.

Sadeghi S, Brooks D, Goldstein RS . Patients' and providers' perceptions of the impact of health literacy on communication in pulmonary rehabilitation. Chron Respir Dis 2013; 10: 65–76.

Whitmarsh A, Koutantji M, Sidell K . Illness perceptions, mood and coping in predicting attendance in cardiac rehabilitation. Br J Health Psychol 2003; 8: 209–221.

Mosleh SM, Bond CM, Lee AJ, Kiger A, Campbell NC . Effectiveness of theory-based invitations to improve attendance at cardiac rehabilitation: A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2014; 13: 201–210.

Graves J, Sandrey V, Graves T, Smith DL . Effectiveness of a group opt-in session on uptake and graduation rates for pulmonary rehabilitation. Chron Respir Dis 2010; 7: 159–164.

Bennion AE, Shaw RL, Gibson JM . What do we know about the experience of age related macular degeneration? A systematic review and meat-synthesis of qualitative research. Soc Sci Med 2012; 75: 976–985.

Popay J, Rogers A, Williams G . Rationale and standards for the systematic review of qualitative literature in health services research. Qual Health Res 1998; 8: 341–351.

Fischer MJ, Scharloo M, Abbnik J, van't Hul A, van Ranst D, Rudolphus A et al. Converns about exercise are related to walk test results in pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with COPD. Int J Behav Med 2012; 19: 39–47.

Noar SM, Crosby R, Benac C, Snow G, Troutman A . Application of the attitude-social influence-efficacy model to condom use among African-American STD clinic patients: implications for tailored health communication. AIDS Behav 2011; 15: 1045–1057.

Moss-Morris R, Weinman J, Petrie KJ, Horne R, Cameron LD, Buick D . The revised illness perception questionnaire (IPQ-R). Psychol Health 2002; 17: 1–16.

Griffiths C, Motlib J, Azad A, Ramsay J, Eldridge S, Feder G et al. Randomised controlled trial of a lay-led self-management programme for Bangladeshi patients with chronic disease. Br J Gen Pract 2005; 55: 831–837.

Andersen AH, Vinther A, Poulsen LL, Mellemgaard A . Do patients with lung cancer benefit from physical exercise? Acta Oncol 2011; 50: 307–313.

Efraimsson EO, Fossum B, Ehrenberg A, Larsson K, Klang B . Use of motivational interviewing in smoking cessation at nurse-led chronic obstructive pulmonary disease clinics. J Adv Nurs 2011; 68: 767–782.

Chew-Graham C, Brooks J, Wearden A, Dowrick C, Peters S . Factors influencing engagement of patients in a novel intervention for CFS/ME: a qualitative study. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2011; 12: 112–122.

Johnston KN, Young M, Grimmer KA, Antic R, Frith PA . Barriers to, and facilitators for, referral to pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD patients from the perspective of Australian general practitioners: a qualitative study. Prim Care Respir J 2013; 22: 319–324.

Zwar NA, Hermiz O, Comino E, Middleton S, Vagholkar S, Xuan W et al. Care of patients with a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cluster randomised trial. Med J Aust 2012; 197: 394–398.

Yohannes AM, Stone RA, Lowe D, Pursey NA, Buckingham RJ, Roberts CM . Pulmonary rehabilitation in the United Kingdom. Chron Respir Dis 2011; 8: 193–199.

Kaptein AA, Scharloo M, Fischer MJ, Snoei L, Cameron LD, Sont JK et al. Illness perceptions and COPD: an emerging field for COPD patient management. J Asthma 2008; 45: 625–629.

Robertson N . Running up that hill: how pulmonary rehabilitation can be enhanced by understanding patient perceptions of their condition. Chron Respir Dis 2010; 7: 203–205.

Lewis A, Bruton A, Donovan-Hall M . Uncertainty prior to pulmonary rehabilitation in primary care: a phenomenological qualitative study in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chron Respir Dis 2014; 11: 173–180.

Harris D, Hayter M, Allender S . Factors affecting the offer of pulmonary rehabilitation to patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by primary care professionals: a qualitative study. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2008; 9: 280–290.

Acknowledgements

Stefan Priebe, Professor of Social Community and Psychiatry, Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London. This article is an independent research arising from a Doctoral Research Fellowship supported by the National Institute for Health Research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health.

Funding

RS was funded under the ‘Doctoral Research Fellowship’ award from the National Institute for Health Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RS was involved in the conception and design, data extraction, data analysis, interpretation of data and drafting of the article manuscript. LS was involved in the data analysis. TM was involved in conducting the quality appraisal. LS, TM and ST were involved in revising the article critically for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Sohanpal, R., Steed, L., Mars, T. et al. Understanding patient participation behaviour in studies of COPD support programmes such as pulmonary rehabilitation and self-management: a qualitative synthesis with application of theory. npj Prim Care Resp Med 25, 15054 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/npjpcrm.2015.54

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npjpcrm.2015.54

This article is cited by

-

Developing a complex intervention whilst considering implementation: the TANDEM (Tailored intervention for ANxiety and DEpression Management) intervention for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Trials (2021)

-

The Perspectives of Patients with Chronic Diseases and Their Caregivers on Self-Management Interventions: A Scoping Review of Reviews

The Patient - Patient-Centered Outcomes Research (2021)

-

Impact of a smartphone application (KAIA COPD app) in combination with Activity Monitoring as a maintenance prOgram following PUlmonary Rehabilitation in COPD: the protocol for the AMOPUR Study, an international, multicenter, parallel group, randomized, controlled study

Trials (2020)

-

Implementing self-management: a mixed methods study of women’s experiences of a postpartum hypertension intervention (SNAP-HT)

Trials (2020)

-

Effects of a long-term home-based exercise training programme using minimal equipment vs. usual care in COPD patients: a study protocol for two multicentre randomised controlled trials (HOMEX-1 and HOMEX-2 trials)

BMC Pulmonary Medicine (2019)