Key Points

-

The cellular degradative process of autophagy participates in multiple aspects of immunity, including cell-autonomous defence, innate immune signalling and antigen presentation.

-

Extensive crosstalk between autophagy and inflammatory signalling cascades ensures a robust immune response towards pathogens while avoiding collateral damage to the host. Several chronic inflammatory disorders are associated with autophagy dysfunction.

-

Pathways that induce autophagy, such as those downstream of pattern recognition receptors, are conversely subject to regulation by autophagy.

-

Autophagy can increase and decrease different components of the same inflammatory signalling cascade in a context-dependent manner.

-

Many immune-related functions of conserved autophagy proteins reflect non-canonical functions of the autophagy machinery, representing new opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

Abstract

Autophagy has broad functions in immunity, ranging from cell-autonomous defence to coordination of complex multicellular immune responses. The successful resolution of infection and avoidance of autoimmunity necessitates efficient and timely communication between autophagy and pathways that sense the immune environment. The recent literature indicates that a variety of immune mediators induce or repress autophagy. It is also becoming increasingly clear that immune signalling cascades are subject to regulation by autophagy, and that a return to homeostasis following a robust immune response is critically dependent on this pathway. Importantly, examples of non-canonical forms of autophagy in mediating immunity are pervasive. In this article, the progress in elucidating mechanisms of crosstalk between autophagy and inflammatory signalling cascades is reviewed. Improved mechanistic understanding of the autophagy machinery offers hope for treating infectious and inflammatory diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Macroautophagy, more commonly referred to simply as autophagy, is a fundamental cellular process in eukaryotes that is essential for responding and adapting to changes in the environment. In its most common form, autophagy involves sequestration of cytosolic material within a double-membrane-bound vesicle, termed the autophagosome, and the subsequent fusion of the autophagosome with endolysosomal vesicles leads to degradation and recycling of the sequestered substrates. A crucial function of autophagy is to breakdown macromolecules such as proteins to provide amino acids and other factors necessary to generate energy and synthesize new proteins. The ability to capture large material distinguishes this pathway from proteasomal degradation, making autophagy necessary for maintaining cellular homeostasis in a variety of settings. Many of the substrates found within autophagosomes are those that threaten cell viability, such as damaged organelles, protein aggregates and intracellular pathogens.

Although autophagosomes are detected under steady-state conditions, their generation is increased substantially in response to stressors, of which nutrient deprivation is the best characterized. Depletion of amino acids or growth factors induces autophagy by inhibiting mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), a master regulator of metabolism that inhibits the ULK1 autophagy complex through phosphorylation under nutrient replete conditions (Box 1). Once freed from inhibition, the ULK1 complex phosphorylates beclin 1 to activate the phosphoinositide 3-kinase catalytic subunit type III (PI3KC3) complex1, which creates phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PtdIns3P)-rich subdomains at regions associated with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), such as the ER–Golgi intermediate compartment or ER–mitochondria contact sites2,3. PtdIns3P-binding proteins then recruit the ATG16L1 complex to this autophagosome precursor site (known as the isolation membrane)4. The ATG16L1 complex anchors the ubiquitin-like molecule LC3 to the lipid bilayer by conjugating LC3 to phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) (Box 1). Next, the LC3–PE complex mediates membrane tethering and fusion to extend the isolation membrane by recruiting lipids, which are likely to be derived from multiple membrane sources, including endosomal vesicles harbouring the transmembrane protein ATG9L1. The growing isolation membrane eventually fuses with itself to form the enclosed double-membrane structure, and class C vacuolar protein sorting (VPS) and SNARE-like proteins mediate fusion with endolysosomal vesicles leading to the degradation and recycling of the contents.

In this article, the function and regulation of autophagy in the context of inflammatory signals is reviewed. It is now appreciated that autophagy is critical to both cell-autonomous defence and multicellular immunity, and autophagy dysfunction appears to be a recurring theme in inflammatory disease. First, the general functions of autophagy in immunity are summarized. The focus of the second section is on specific modes of intersection between autophagy and immune pathways, specifically signalling pathways downstream of innate immune sensors. The third section provides examples of how these mechanisms contribute to multicellular immune responses, with an emphasis on adaptive immunity and inflammatory disease. Finally, the barriers for targeting the autophagy pathway to treat disease are discussed.

The role of autophagy in immunity

Autophagy can eliminate an infectious threat by promoting a form of autophagy termed xenophagy, whereby intracellular pathogens such as viruses, bacteria and protozoa are trapped within an autophagosome and targeted to the lysosome for destruction. Xenophagy depends on adaptor molecules that crosslink pathogens with the autophagy machinery. For instance, sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1; also known as p62), nuclear domain 10 protein NDP52, optineurin (OPTN) and TAX1-binding protein 1 (TAX1BP1) bind LC3, in conjunction with host molecules associated with damaged Salmonella-containing vacuoles, including ubiquitin and galectin 8 (Ref. 5). These binding events allow the isolation membrane to grow around the bacteria, resulting in its sequestration within the autophagosome. One of the most compelling evidence that autophagy is an important cell-intrinsic defence mechanism is that many invasive pathogens encode virulence factors that counteract the pathway, as exemplified by the LC3-deconjugating enzyme RavZ secreted by Legionella pneumophila6. Also, enteroviruses can use autophagy to provide a membrane coat that enhances cell-to-cell spread7.

Some pathogens are neutralized by non-canonical functions of the autophagy machinery, herein referred to as 'non-canonical autophagy' (Box 2). For instance, LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP) mediates phagosome maturation and requires many of the same proteins as conventional autophagy, but it occurs independently of autophagosome formation8. Another form of non-canonical autophagy induced by interferon-γ (IFNγ) restricts the replication of norovirus and Toxoplasma gondii in macrophages in a lysosome-independent manner9,10,11. In the case of T. gondii infection, the ATG16L1 complex and LC3 disrupt the parasitophorous vacuole by recruiting the p47 immunity-related GTPases (IRGs) and the p65 guanylate-binding proteins (GBPs)9,12,13,14,15. Although it is not always clear whether the classical or an unconventional form of autophagy is involved in host defence, autophagy proteins remain strong candidates as drug targets in infectious disease. Indeed, inducing autophagy with a cell-permeable beclin 1 peptide protects against several pathogens in vitro and in vivo, including chikungunya virus and West Nile virus16.

Autophagy also reduces the amount of damage caused by pathogens. For example, during Sindbis virus infection, autophagy protects against neuronal cell death without affecting the degree of viral replication17. Similarly, in the absence of ATG16L1, the beneficial intestinal virus murine norovirus (MNV)18 triggers intestinal pathologies in mice through the cytokines tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and IFNγ19. Viral replication is unaltered in these mice19, consistent with a role for autophagy in suppressing the negative impact of inflammatory cytokines produced in responses to an enteric virus. Furthermore, expression of transcription factor EB (TFEB), a master regulator of autophagy and lysosomal genes, protects Caenorhabditis elegans from Staphylococcus aureus infection by promoting a cytoprotective transcriptional response20. Autophagy is also essential for the survival of mice with S. aureus-mediated bacteraemia and pneumonia: instead of reducing bacterial burden in these animals, autophagy promotes the viability of endothelial cells in the presence of a pore-forming toxin produced by widely circulating methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains21. The vulnerability of autophagy-deficient endothelial cells is due to an increase in the expression of the toxin receptor ADAM10 at the protein level21, indicating that the protein turnover function of autophagy can indirectly contribute to infectious disease susceptibility. Therapeutically increasing autophagy also improves survival in a mouse model of sepsis by reducing the level of inflammation in the lungs22. Thus, in addition to resistance mechanisms aimed at reducing the number of intracellular infectious agents, autophagy facilitates tolerance mechanisms that reduce the adverse effect of an infection23.

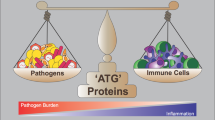

A related function of autophagy is to inhibit the production of soluble inflammatory mediators, which can come at the cost of diminishing host defence. Deficiency in autophagy proteins protects against intestinal infection by Citrobacter rodentium, improves survival during lung infection by influenza virus and prevents reactivation of latent murine herpesvirus 68 (MHV68)24,25,26. The enhanced host defence in these models is associated with large scale increases in cytokine levels and/or inflammatory gene expression. Although inhibition of autophagy confers a short-term benefit during infection by these specific pathogens, the long-term consequence of this heightened immunity may be chronic inflammatory disease. Additionally, as the above examples with S. aureus, Sindbis virus and a large number of other studies illustrate, autophagy is usually beneficial to the host during a life-threatening infection. Therefore, the ultimate function of autophagy in immunity may be to mediate a balanced immune response whereby the majority of infectious threats are neutralized while minimizing damage to the host, thereby staving off long-term disease.

Convergence of autophagy and immune signalling

Amino acid starvation during bacterial infection can induce autophagy27, raising the possibility that sensing changes in nutrient availability is an ancient mechanism to initiate autophagy in response to infectious threats. As the immune system evolved, autophagy and related pathways have been integrated into the complex signalling networks that coordinate multicellular defence strategies. An array of pathogen- and damage-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs and DAMPs) can induce or inhibit autophagy in specific contexts. In addition, autophagy can feedback on the process of PAMP and DAMP recognition to suppress an over-exuberant response. This creates a set of feedback loops between autophagy and immune signalling pathways that mediate host defence while limiting tissue damage.

NOD-like receptors. NOD-like receptors (NLRs) are cytosolic sensors of PAMPs and DAMPs. Many NLRs are inflammasome subunits that mediate interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18 production and pyroptosis. The NLRP3 inflammasome, for instance, is activated by diverse stimuli that disrupt mitochondrial integrity, including ATP, bacterial toxins and uric acid crystals. Mitophagy, which is a selective form of autophagy that removes damaged mitochondria, inhibits IL-1β and IL-18 production in response to these stimuli by preventing the accumulation of mitochondria-derived DAMPs, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)28,29,30 (Fig. 1). Autophagy also removes or prevents leakage of bacterial products from Shigella- or Salmonella-containing vacuoles into the cytoplasm, thereby limiting the detection of microbial factors in the cytosol by the caspase 11 inflammasome31,32. This model is consistent with a role for autophagy in repairing damaged pathogen-containing vacuoles33 and with the observation that autophagy prevents pyroptosis in the presence of invasive bacteria32,34,35. In addition to these examples, in which autophagy limits the availability in the cytosol of inflammasome activators (such as ROS, mtDNA and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)), one study has shown that SQSTM1 can target the inflammasome subunit ASC for incorporation into an autophagosome, leading to its inactivation36. These examples illustrate the crucial role of autophagy in suppressing inflammation through the removal of PAMPs, DAMPs and inflammatory signalling intermediates from the cytosol, a theme that will be reinforced throughout this article.

Exposure to exogenous agents including ATP, bacterial toxins and uric acid crystals damages mitochondria, which results in the release of factors such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) that activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. Autophagy inhibits inflammasome activation by sequestering damaged mitochondria and the NLRP3-binding protein ASC to prevent caspase 1-mediated cleavage of pro-interleukin-1β (pro-IL-1β) and pro-IL-18 into the active forms, as well as to prevent pyroptosis. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2 (NOD2) in the cytosol recognizes bacterial peptidoglycan and viral RNA from internalized pathogens and subsequently induces autophagy, either by signalling through receptor-interacting protein 2 (RIP2) or by directly recruiting ATG16L1 in a complex with immunity-related GTPase family M protein (IRGM). Incorporation of the bacteria into the autophagosome is achieved by LC3-binding proteins, such as sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1), optineurin (OPTN) and NDP52, which recognize the damaged vacuole or mitochondrion tagged by ubiquitin and galectin 8 (GAL8). In addition to inhibiting pathogen replication, this process reduces leakage of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) into the cytosol to prevent activation of the caspase 11 inflammasome. Following LPS-mediated activation of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), myeloid differentiation primary-response protein 88 (MYD88) and TIR-domain-containing adaptor protein inducing IFNβ (TRIF) signal through TNFR-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) and TRAF3 to facilitate autophagy by inducing the K63-linked ubiquitylation and release of beclin 1 from inhibition, through the phosphorylation and activation of OPTN through TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) ubiquitylation, and by inducing nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signalling and transcription of SQSTM1 and the autophagosome maturation protein DNA damage-regulated autophagy modulator protein 1 (DRAM1). Recognition of internalized fungal glycans and immune complexes by TLR2 and the Fcγ receptor (FcγR) triggers LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP). As the phagosome acidifies, the fungal pathogen is degraded and activates TLR9 to induce signals through interferon regulatory factor 7 (IRF7) and type I interferon (IFN) transcription. PI3KC3, phosphoinositide 3-kinase catalytic subunit type III.

NLRs also have a role in inducing autophagy in response to the presence of PAMPs and DAMPs in the cytosol. The sensing of uric acid and nigericin by NLRP3, or recognition of poly(dA:dT) double-stranded DNA by AIM2, induces autophagy by triggering nucleotide exchange on the small GTPase RALB36. Amino acid deprivation also signals through RALB to induce autophagy by creating a large multiprotein complex with the exocyst complex component EXO84 that links the ULK1 and PI3KC3 complexes37. Interestingly, autophagy induction downstream of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) kinase GCN2, which senses amino acid depletion, dampens inflammasome-mediated intestinal damage following chemical injury38. Thus, nutrient sensing pathways may have been repurposed for inducing autophagy during inflammatory stress.

NLR activation by infectious agents generally induces autophagy. During L. pneumophila infection of macrophages, flagellin that leaks from the vacuole into the cytosol is recognized by NLR family, apoptosis inhibitory protein 5 (NAIP5) and NLRC4, and the formation of the inflammasome complex induces autophagy by releasing beclin 1 from an inhibitory interaction with NLRC4 (Ref. 35). Also, the NLRP6 inflammasome is required for autophagosome formation in the intestinal epithelium39. Together, these examples indicate that activation of inflammasomes is coupled with induction of autophagy, which is most likely to reflect a regulatory feedback loop that allows some inflammasome activation essential for defence but prevents irreparable damage to the host by inhibiting excessive cytokine release and pyroptosis by the inflammasome.

Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 1 (NOD1) and NOD2, the founding members of the NLR family, also induce autophagy. In the presence of bacterial peptidoglycan derivatives, these molecules signal through the adaptor kinase receptor-interacting protein 2 (RIP2) to induce nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling. Both NOD1 and NOD2 mediate the recruitment of LC3 to vesicles containing internalized bacteria to initiate xenophagy (Fig. 1), but there is disagreement regarding whether this process involves signalling through RIP2 or direct binding between the NLR and ATG16L1 (Refs 40,41,42,43,44,45).

The induction of autophagy following NOD1 and NOD2 activation can dampen an immune response. Specifically, cytokine production by myeloid cells in the presence of bacteria or bacterial ligands that activate NOD2 is increased in the absence of autophagy proteins46,47,48,49. NOD2 also recognizes viral RNA, and subsequent RIP2 signalling induces mitophagy through ULK1 phosphorylation. Consequently, NOD2 or RIP2 deficiency increases ROS production by mitochondria and NLRP3 inflammasome activation, which exacerbates lung inflammation during influenza virus infection50. Similarly, NOD2–RIP2 signalling induces autophagy in alveolar macrophages to suppress inflammation caused by the inflammasome during acute lung injury51. Additionally, following internalization of outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) derived from the commensal bacterium Bacteroides fragilis, NOD2 is required for induction of a LAP-like process in dendritic cells (DCs) in the intestine that mediates regulatory T cell (Treg cell) differentiation — a process that prevents an unwanted inflammatory response directed towards the microbiota52. Although the mechanistic contribution of LAP in this setting remains unclear, this study demonstrates a novel role for non-canonical autophagy in suppressing immune responses at barrier sites where microbial encounters are common. Altogether, these studies indicate that a major function of autophagy is to keep the immune system in check by counteracting the pro-inflammatory functions of NLRs.

Toll-like receptors. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) sense PAMPs at the cell surface or in the lumen of vesicles and signal through the adaptor proteins myeloid differentiation primary-response protein 88 (MYD88) and/or TIR-domain-containing adaptor protein inducing IFNβ (TRIF) to activate TNFR-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), which catalyses lysine 63 (K63) ubiquitylation of several signalling intermediates upstream of NF-κB and MAPK to induce inflammatory gene expression. Both MYD88 and TRIF signalling promote autophagosome formation (Fig. 1), perhaps explaining why a broad range of TLR ligands can induce autophagy53,54. On LPS exposure, TLR4 promotes the assembly of the PI3KC3 complex through TRAF6-mediated K63 ubiquitylation of beclin 1 to free it from an inhibitory interaction with B cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2)55. Signalling through MYD88 and NF-κB further increases autophagosome maturation by inducing the expression of DNA damage-regulated autophagy modulator protein 1 (DRAM1), a lysosomal transmembrane protein involved in lysosomal acidification56. The ability to target specific substrates to the autophagosome is facilitated by the transcriptional induction of SQSTM1 downstream of TLR4 (Ref. 57). In addition, LPS- and NF-κB-induced SQSTM1 recognizes ubiquitin-tagged mitochondria to promote mitophagy-mediated suppression of the NLRP3 inflammasome30 (Fig. 1). Thus, the induction of SQSTM1 explains why NF-κB signalling is sometimes counterintuitively anti-inflammatory.

TLR4–TRIF activation by Gram-negative bacteria can also induce TRAF3-mediated K63 ubiquitylation of TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), which phosphorylates optineurin to increase its binding affinity for LC3, thereby promoting xenophagy by crosslinking LC3 and bacteria bound by OPTN58. These studies indicate that pathogen sensing by TLRs triggers multiple signalling events that converge on autophagy.

Importantly, TLR-mediated induction of autophagy has been validated in vivo. Rift Valley fever virus triggers autophagy downstream of TLR7 signalling to restrict viral replication in Drosophila melanogaster59. In mice, MYD88-dependent induction of autophagy in the intestinal epithelium prevents dissemination of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium60. Unlike NLRs in the cytosol, the ability to detect the presence of PAMPs before a breach in the cell membrane may explain why a role for TLR-induced autophagy can be detected as early as 24 hours post-infection in this setting.

Communication between autophagy and TLRs is bi-directional. Autophagy delivers viral RNA to the endosome for TLR7 recognition in plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs)61. In at least some examples, gene expression downstream of TLRs requires the recruitment of LC3 to phagosomes through LAP (Fig. 1). When antibody-bound DNA complexes are internalized by pDCs and bind Fcγ receptor (FcγR), LAP mediates the maturation of the phagosome to a vesicle that supports type I IFN production downstream of TLR9 (Ref. 62). The acidification of phagosomes containing TLR2 ligands in macrophages also occurs through LAP63. Furthermore, melanin in the cell wall of the fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus inhibits ROS production by the NADPH oxidase, which, together with TLR recognition of fungal surface molecules, is a necessary step in the recruitment of autophagy proteins to the phagosome. When melanin is removed during A. fumigatus germination, LAP can mediate the degradation of the pathogen by promoting phagosome maturation8,64. These findings demonstrate how autophagy and LAP support vesicle trafficking events that are crucial for TLR-mediated cytokine production and pathogen degradation.

In contrast to the above examples, there are situations in which autophagy proteins and TLRs have an antagonistic relationship. SQSTM1 has a dual function as both an adaptor molecule for autophagy and a scaffolding protein that binds TRAF6 to mediate NF-κB signalling downstream of TLRs65. In keratinocytes, SQSTM1 is targeted for autophagic degradation through its binding to LC3, thereby disrupting TLR4 and TLR2 signalling66. Furthermore, MYD88 signalling upon TLR2 recognition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces a microRNA that inhibits autophagy by targeting UVRAG, a subunit of the PI3K3C complex, resulting in increased bacterial survival67. However, unlike the extensive antagonistic relationship observed between NLRs and autophagy, examples of autophagy and TLR antagonism have thus far been rare and may apply to specific cell types or pathogens.

Antiviral signalling. Whereas autophagy proteins typically promote TLR signalling in the presence of vesicle-bound nucleic acid, autophagy proteins mediate mitophagy to inhibit signalling downstream of cytosolic sensors of viral nucleic acid. The retinoic acid inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs) RIG-I and melanoma differentiation associated gene 5 (MDA5) sense double-stranded RNA in the cytosol and signal through mitochondrial antiviral signalling protein (MAVS), which oligomerizes on the mitochondrial outer-membrane to induce type I IFN expression by activating the transcription factors IRF3 and IRF7. Mitophagy suppresses type I IFN production by removing the platform for RLR signalling and causes degradation of signalling intermediates such as MAVS68,69,70 (Fig. 2a). ROS produced by accumulating mitochondria also contributes to excess type I IFN production when mitophagy is inhibited71. When MAVS signalling is triggered by a viral infection, the ATG16L1 complex is recruited to mitochondria by NLR family member X1 (NLRX1), elongation factor Tu, mitochondria (TUFM) and cytochrome c oxidase subunit 5B (COX5B)68,70 (Fig. 2a). For this reason, cells deficient in autophagy proteins, NLRX1 or COX5B display enhanced type I IFN production and are better able to restrict the replication of a variety of viruses68,69,70,71,72. Presumably, mitophagy is coupled to the detection of cytosolic RNA to prevent sustained, pathological type I IFN production, but this model has not been formally demonstrated.

a | Several examples have been reported in which autophagy regulates cytokine production, or is subject to regulation by cytokines. The recognition of viral RNA by retinoic acid inducible gene I (RIG-I) induces mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and mitochondrial antiviral signalling protein (MAVS) signalling, leading to type I interferon (IFN) transcription. The recruitment of the ATG16L1 complex by NLR family member X1 (NLRX1) and elongation factor Tu, mitochondria (TUFM; or COX5B, not shown) to the mitochondrion promotes mitophagy thereby inhibiting type I IFN production by removing the MAVS signalling platform and inhibiting ROS production. b | Cyclic GMP–AMP synthase (cGAS) converts cytosolic DNA (from viruses, bacteria or the host) to cyclic dinucleotides for recognition by stimulator of interferon genes (STING) and subsequent type I IFN production. cGAS activates ULK1, which mediates an inhibitory phosphorylation of STING. Also, the binding of beclin 1 to cGAS allows beclin 1 to induce autophagy through the PI3KC3 complex to remove the cytosolic DNA and simultaneously inhibits cGAS-dependent type I IFN production. c | IFNγ induces autophagy through Janus kinase 1 (JAK1), JAK2 and p38. This pathway is reinforced by mitophogy, which reduces the levels of mitochondrial ROS that activate SHP2, an inhibitor of IFNγ signalling. By contrast, interleukin-10 (IL-10) can inhibit autophagy by promoting binding between signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and protein kinase R (PKR), which inhibits the activation of the autophagy inducer eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α). d | In addition to suppressing IL-1β production by inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome, autophagy mediates the secretion of IL-1β. Extracellular IL-1β signals through IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) and myeloid differentiation primary-response protein 88 (MYD88) to induce autophagy, and autophagosome maturation and degradation of engulfed material including intracellular bacteria is dependent on TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and suppresses the NLRP3 inflammasome. e | High mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), both within the cell and upon release by dying cells, promotes autophagy. Binding of extracellular HMGB1 by receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) induces autophagy by inhibiting mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR). Nuclear HMGB1 promotes mitophagy by inducing the expression of ROS, it induces autophagy by protecting beclin 1 from an inhibitory interaction with B cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) or cleavage by calpain (not shown). HSPB1, heat shock protein B1.

Autophagy proteins are also involved in sensing cytosolic DNA, which is associated with viral infection, intracellular bacteria and autoimmunity. Cyclic dinucleotides generated by cyclic GMP–AMP synthase (cGAS) in the presence of double-stranded DNA activate the transmembrane protein stimulator of interferon genes (STING) to induce type I IFN expression. STING colocalizes with autophagy proteins including LC3, and loss of ATG9L1 leads to aberrant STING trafficking and activation73. However, STING function was unaffected by the deletion of the canonical autophagy protein ATG7 (Ref. 73), implicating a non-canonical autophagy pathway in mediating STING localization. In another departure from canonical autophagy, ULK1 functions downstream of the PI3KC component VPS34 in this setting. Similar to autophagy induction during glucose starvation, cyclic dinucleotides induce the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), which leads to phosphorylation and activation of ULK1 (Ref. 74). Instead of inducing autophagy, ULK1 phosphorylates STING to inhibit IRF3 and aberrant type I IFN hyperexpression74 (Fig. 2b).

Other examples in which autophagy proteins intersect with cytosolic DNA sensing are more consistent with their functions in canonical autophagy. During herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV1) infection, beclin 1 binds and inhibits cGAS, which frees beclin 1 from inhibition by rubicon (run domain beclin 1-interacting and cysteine-rich domain-containing protein) to enhance PI3KC3 activity and autophagy-mediated degradation of viral DNA, thus reducing both the amount of cytosolic DNA and the levels of type I IFN production75 (Fig. 2b). Autophagy also prevents pathological STING activation by targeting damaged DNA that leaks from the nucleus to the lysosome where it is degraded by DNase2A76.

Spontaneous type I IFN signalling occurs upon autophagy inhibition in intestinal tissue and tumour cells24,77,78, indicating that autophagy in some organs or cell types is constitutively suppressing cytokine release. A type I IFN signature in the absence of an infectious trigger could reflect an inappropriate immune response to host nucleic acid, the microbiota and/or endogenous retroviruses. Given our growing appreciation of the contribution of type I IFN to cancer and autoimmunity, this autophagy-mediated control of cytokine expression under steady-state conditions is likely to be relevant to situations beyond infectious disease.

Cytokines. The T helper 1 (TH1) cytokines IFNγ and TNF generally upregulate xenophagy in target cells79,80,81, which is consistent with a role of autophagy in supporting cellular immunity. IFNγ induces autophagy through the Janus kinase 1 (JAK1)–JAK2 and p38 MAPK pathway, independently of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1)82. In turn, autophagy promotes IFNγ signalling by limiting ROS production, which, if left to accumulate, would activate the JAK–STAT inhibitory phosphatase SHP2 (Ref. 83) (Fig. 2c).

In addition to conventional autophagy, IFNγ induces a LAP-like process in hepatocytes infected by the malarial parasite Plasmodium vivax. The deposition of LC3 onto the parasitophorous vacuole leads to the recruitment of lysosomes and killing of the parasite84. As mentioned earlier, IFNγ suppresses T. gondii and norovirus replication through an incompletely understood type of non-canonical autophagy9,10,11. Therefore, IFNγ induces canonical and non-canonical autophagy to inhibit intracellular pathogen replication.

By contrast, cytokines that signal through other STAT molecules can inhibit autophagy. Binding of protein kinase R (PKR) by STAT3 prevents PKR-mediated phosphorylation of eIF2α, a stress-responsive regulator of translation that promotes autophagy85 (Fig. 2c). Therefore, any cytokine that activates STAT3 can theoretically interfere with autophagy, as seen with the regulatory cytokine IL-10 (Ref. 86). STAT6 signalling downstream of the TH2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 also inhibits the induction of autophagy by IFNγ in macrophages80. However, DCs that differentiate in the presence of IL-4 display increased expression of RUFY4, a positive regulator of autophagosome growth and fusion with lysosomes87, suggesting that IL-4 can also enhance autophagy. The amount of time the cell is exposed to the TH2 cytokines, and the presence of other cytokines such as IFNγ and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), may explain these contradictory effects of TH2 cytokines on autophagy. These studies establish a link between autophagy and TH2 and regulatory cytokines, but the impact of this link on host defence requires further investigation.

As mentioned above, autophagy inhibits IL-1β production by repressing inflammasome activation but, conversely, can facilitate the secretion of this cytokine88. IL-1β does not undergo conventional secretion owing to the absence of a signal peptide, but it can pass through a permeabilized plasma membrane89. Alternatively, when membrane integrity is intact, IL-1β can be incorporated into the space between the inner- and outer-membrane of the autophagosome and is released from the cell following autophagosome fusion with the plasma membrane or multivesicular body90 (Fig. 2d). However, IL-1β is ultimately released from autophagy-deficient cells, probably through the permeabilized membrane that accompanies increased inflammasome activity and pyroptosis. Once secreted, IL-1β continues to influence autophagy in the target cell through TBK1, which interacts with RAB8B, to promote autophagosome maturation91 (Fig. 2d). In addition, IL-1β (as well as IL-1α and IFNγ) induces ubiquitylation of beclin 1, suggesting that it can activate autophagy through a mechanism similar to that of LPS activation (Fig. 1).

Although less appreciated, autophagy inhibits the production of other cytokines. For instance, secretion of other IL-1 family members, specifically IL-1α and migration inhibitory factor (MIF), is increased in autophagy-deficient macrophages as a downstream consequence of mitochondrial ROS accumulation92,93. Autophagy may be particularly important for preventing TH17 cell responses because the cytokines that are suppressed by autophagy are key to inducing IL-17 expression by T cells: IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-18, IL-23, IL-6, transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) and macrophage MIF47,92,93,94,95. Excess IL-1α released by autophagy-deficient macrophages induces TH17 cell differentiation and exacerbates lung inflammation during M. tuberculosis infection92 (Fig. 3). Similarly, IL-1β produced following autophagy inhibition in DCs acts in an autocrine manner to mediate IL-23 production, leading to IL-17 secretion by γδ T cells94. It is less clear whether TH1 cells and other branches of adaptive immunity are enhanced by autophagy deficiency in macrophages and DCs. One reason may be that type I IFN, which is over-produced upon autophagy inhibition, inhibits IFNγ activity96. An inflammatory milieu could also cause T cell exhaustion. As discussed later, the role of autophagy in antigen presentation is another variable that requires consideration.

Autophagy activity in T cells, antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and dying cells affects T cell immunity. Autophagy in APCs such as dendritic cells delivers intracellular and extracellular antigens to endolysosomal vesicles where they are loaded onto MHC class II molecules for presentation to CD4+ T cells. Peptidylarginine deiminases (PADs) in autophagosomes generate citrullinated peptides, thereby affecting the repertoire of antigens being presented. Extracellular antigens can also be delivered to the endosolysosome by LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP). Autophagy-mediated release of ATP by dying cells, such as those infected by viruses, leads to engulfment by the APC. Internalized antigens from the dying cell can then be cross-presented on MHC class I molecules (in the endolysosome) to stimulate CD8+ T cells, a process mediated by autophagy or, potentially, LAP downstream of GCN2 activation. By inhibiting the release of key inflammatory cytokines, autophagy decreases the differentiation of CD4+ T cells into T helper 17 (TH17) cells. Alternatively, exogenous antigens may be exported into the cytosol and delivered to MHC class I molecules in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). For instance, the removal of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-producing mitochondria inhibits calpain-mediated processing of interleukin-1α (IL-1α). Naive CD4+ T cells require autophagy for survival and proliferation (and cytokine production once activated). The establishment of memory by CD8+ T cells is also dependent on autophagy.

DAMPs. Cell death can lead to extracellular release of DAMPs that are usually confined within the cell, such as nucleic acids, ATP, high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) and IL-1β. Purinergic receptors and transporters that recognize exogenous ATP trigger autophagy through AMPK-mediated mTOR inhibition and dephosphorylation of AKT97,98,99,100. Before cell death, autophagy promotes the secretion of ATP by mediating the migration of ATP-containing lysosomes towards the plasma membrane101. Owing to the importance of ATP as a chemotactic signal, loss of autophagy in tumour cells diminishes the ability of chemotherapeutic agents to trigger a robust antitumor immune response102. Thus, autophagy is induced by ATP and also promotes the secretion of ATP.

Like IL-1β, autophagy facilitates the release of HMGB1, a chromatin-associated nuclear protein, from stressed or dying tumour cells103. Extracellular HMGB1 is recognized by receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), resulting in decreased mTOR activity and increased autophagy104. Nuclear HMGB1 regulates the expression of heat shock protein B1 (HSPB1), a chaperone protein that promotes mitophagy105. Also, HMGB1 translocates to the cytosol in the presence of ROS, where it induces autophagy by releasing beclin 1 from inhibition by BCL-2 (Ref. 103). Endogenous HMGB1 can also promote autophagy by protecting beclin 1 and ATG5 from calpain-mediated cleavage106 (Fig. 2e). Thus, when HMGB1 is removed from macrophages or intestinal epithelial cells, the balance shifts from autophagy to apoptosis and favours exaggerated cytokine production to increase inflammation106,107.

To summarize, extensive crosstalk has been observed between autophagy and immune signalling cascades downstream of the array of receptors that recognize PAMPs, DAMPs and cytokines. The finding that autophagy is sometimes necessary for type I IFN production (for example, by functioning together with TLRs in pDCs) but can also dampen type I IFN signalling (for example, through mitophagy) reinforces the fact that the relationship between autophagy and a given immune pathway is context dependent. However, one recurring observation is that pathways that induce autophagy are often inhibited by autophagy to prevent sustained activation. This negative-feedback loop is most obvious in the presence of inflammasome substrates and viral nucleic acids in the cytosol, where autophagy limits the levels of cytokines produced upon sensing of these molecules. This function of autophagy is not mutually exclusive from its antimicrobial functions (as in the case of xenophagy); removing the infectious threat and removing the PAMPs that triggers the inflammatory response are both ways to restore homeostasis.

Autophagy in immunity and disease

Autophagy and adaptive immunity. A role for autophagy can be seen in virtually all the cell types that participate in adaptive immunity: lymphocytes, antigen-presenting cells (APCs), dying cells and myeloid cells that contribute to the inflammatory milieu. Autophagy, most likely through the removal of damaged mitochondria, is necessary for the survival and proliferation of CD4+, CD8+ and NK T cells108,109,110,111,112,113,114, memory responses of CD8+ T cells and activated NK cell maintenance115,116,117,118,119. In addition, autophagy activity generates the ATP necessary for IL-2 and IFNγ production by effector CD4+ T cells120. Autophagy may have analogous functions in maintaining organelle and metabolic homeostasis in the B cell lineage because Atg5 deletion leads to an absence of B1a B cells and a defect in antibody production by plasma cells121,122,123.

The induction of autophagy in naive CD4+ T cells following TCR stimulation is dependent on mTOR inhibition downstream of the ubiquitin-editing enzyme A20 (also known as TNFAIP3)114. TCR engagement also induces autophagy-mediated degradation of BCL-10 upstream of NF-κB, thus preventing hyperactivation of effector T cells124. Autophagy also has an important role in maintaining Treg cells, as inhibition of autophagy causes apoptosis of Treg cells and lineage instability, due to aberrant metabolism, which leads to unrestrained TH2 cell responses and inflammation at intestinal barrier sites125,126. As expected, the role of autophagy in supporting these various lymphocyte lineages is necessary for optimal immune responses to viruses, parasites, self-antigens and tumours115,122,125,126.

On the APC side, autophagy affects the repertoire of peptides presented on MHC class II molecules127, including by thymic epithelial cells that mediate the selection of developing thymocytes128. The presentation of specific antigens has been shown to depend on autophagy: for example, autophagosomes transport peptidylarginine deiminases (PADs; which convert arginine to citrulline) to antigen-containing endolysosome, leading to the generation of citrullinated self-peptides implicated in rheumatoid arthritis129 (Fig. 3). Autophagy in virally infected cells generates antigens for presentation to CD4+ T cells by delivering cytosolic proteins to the endolysosome for antigen processing, such as the Epstein–Barr virus protein EBNA1 (Ref. 130) (Fig. 3). In some cases, antigens are generated by autophagy from the uptake of ubiquitylated protein aggregates and pathogen-containing vacuoles that are recognized by SQSTM1, which become substrates for either MHC class I or MHC class II presentation131,132. Autophagy can be augmented to enhance antigen presentation through various signals, such as IFNγ and NOD2 activation41,131,132. Autophagy or LAP has also been shown to be crucial for the processing of exogenous antigens in DCs by mediating the fusion of phagosomes containing TLR ligands or apoptotic corpses with lysosomes133,134,135 (Fig. 3). This process is necessary for the MHC class II presentation that drives the antiviral TH1 cell response during HSV2 infection136. Therefore, it is possible that the reason pathogens encode proteins that inhibit autophagy is to avoid recognition by CD4+ T cells. For instance, the HSV1 protein ICP34.5 binds beclin 1 to inhibit autophagy-mediated MHC class II antigen presentation in DCs137.

DCs can also present exogenous antigens on MHC class I molecules through cross-presentation. Vaccination of humans with the yellow fever virus vaccine YF-17D induces autophagy in DCs through induction of the amino acid starvation sensor GCN2. Inhibition of either autophagy proteins or GCN2 impairs the ability of DCs to mediate proliferation of CD8+ T cells when co-cultured with infected cells138 (Fig. 3). This study provides a clinically relevant example of autophagy-dependent MHC class I cross-presentation. However, as with certain examples of antigen presentation by MHC class II molecules, the role for autophagy proteins revealed by this study may reflect LAP rather than autophagy. Now that new tools are available, future studies will be able to distinguish the role of canonical versus non-canonical forms of autophagy in antigen presentation.

ATG16L1 in Crohn disease and graft-versus-host disease. Genetic variants that occur near or within autophagy genes are implicated in several inflammatory disorders (Table 1). One of the first indicators that autophagy dysfunction contributes to inflammatory disease was provided by the genetic link between Crohn disease and a common polymorphism in ATG16L1 (Ref. 139). The disease polymorphism results in a threonine to alanine coding change (T300A) that destabilizes the ATG16L1 protein product by introducing a caspase 3 cleavage site48,49. The function of autophagy in inhibiting cytokine production is consistent with the idea that Crohn disease stems from an exaggerated immune response directed towards the gut microbiota. Additionally, inhibiting autophagy within the intestinal epithelium causes defects in antimicrobial granule formation by Paneth cells and reduced mucus secretion by goblet cells19,140,141,142. Together with xenophagy, autophagy helps maintain these secretory cell lineages and prevents breaches of the epithelial barrier by both pathogenic and commensal bacteria60,143. The importance of these epithelial cell-specific functions of autophagy is supported by the observation that knock-in mice harbouring the ATG16L1T300A disease variant are susceptible to enteric bacterial infections and display defects in Paneth cells and goblet cells48,49. Also, the crosstalk between the ER stress pathway and autophagy in Paneth cells was shown to have a central role in preventing intestinal inflammation142, directly implicating the organelle homeostasis function of autophagy in the function of this secretory cell type.

The same ATG16L1T300A polymorphism increases the risk of death following allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT)144. Autophagy was found to prevent lethal graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in a preclinical animal model of HSCT by suppressing DC hyperactivity. These autophagy-deficient DCs displayed increased expression of genes implicated in endolysosomal trafficking, including those that affect NF-κB and MAPK signalling144. Allogeneic T cell activation has fewer constraints on the antigen being presented than syngeneic T cell activation, which many explain why autophagy suppresses rather than promotes the ability of DCs to stimulate T cells in this situation. Given that GVHD frequently affects the gut, it would be interesting to determine whether autophagy in the intestinal epithelium also has a role in preventing disease following HSCT.

ATG5 non-coding variants. Polymorphisms associated with increased ATG5 expression are linked to asthma and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)145,146. Although it remains possible that these polymorphisms act through neighbouring genes and not through ATG5, autophagy contributes to biological processes that are relevant to these disorders including regulation of the cytokine milieu and antigen presentation. In airway epithelial cells, autophagy mediates goblet cell differentiation and mucus secretion in response to IL-13 (Ref. 147), suggesting that enhanced autophagy contributes to the pathological overproduction of mucus observed in asthmatic individuals.

Markers of increased autophagy have been observed in B cells and T cells from patients with SLE148,149, which could reflect their genetic predisposition, or an attempt to further restrict cytokine production. The multi-organ inflammation observed in SLE is associated with immune complexes consisting of antibodies bound to nucleic acid and histones, which induce aberrant type I IFN production following their recognition by TLR7 and TLR9. LAP, which is dependent on ATG5, mediates TLR9 activation and type I IFN production by promoting the maturation of the endosome containing these immune complexes after uptake by pDCs62. Also, ATG5 in B cells is necessary for TLR7-dependent generation of autoantibodies and for the induction of SLE pathologies, hinting at a role for autophagy proteins early in disease progression150.

By contrast, ATG5 and other autophagy proteins prevent the production of self-reactive antibodies in myeloid cells. In LAP-deficient mice, dying cells taken up by macrophages are not properly degraded, leading to a general increase in serological markers of inflammation and signs of SLE with age151. Of note, rubicon-deficient mice (one of the LAP-deficient mouse strains used in this study) are known to display increased autophagy8. One interpretation of this result is that loss of LAP in myeloid cells has a greater impact on the development of SLE (in aged mice) than a potential increase in autophagy, which in B cells is predicted to promote autoantibody generation150. Studies that examine the effect of increased autophagy specifically in B cells are warranted.

Inflammatory disease accompanied by autophagy dysfunction. The list of immunological diseases accompanied by autophagy dysfunction extends beyond those caused by mutations in autophagy genes. Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) occurs in individuals harbouring loss-of-function mutations in subunits of the NADPH oxidase, which is necessary for generating ROS and recruiting LC3 to the phagosome152. Monocytes from patients with CGD are defective in LAP-mediated control of A. fumigatus64. Similarly, APCs deficient in NAPDH oxidase activity display reduced MHC class I and MHC class II presentation of fungal antigens133,153. Cells from patients with CGD also display defects in autophagy-mediated suppression of IL-1β in the presence of the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi47. This failure of autophagy-mediated control of IL-1β production contributes to TH17 cell-driven colitis in these patients, which can be treated with an antibody against IL-1R (anakinra)154.

A defect in pathogen handling through autophagy may also explain why individuals with the lysosomal storage disorder Niemen–Pick disease type C 1 (NPC1) sometimes develop granulomatous inflammation in the intestine that resembles Crohn disease. A recent study has shown that macrophages derived from patients with NPC1 are unable to perform NOD2-mediated xenophagy155. In another example, a mutation in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance receptor (CFTR) leads to sequestration of the PI3KC3 complex into protein aggregates and downregulation of autophagy156. This block in autophagy potentially contributes to chronic lung inflammation and recurring pulmonary infections characteristic of cystic fibrosis. Indeed, the CFTR mutation increases the susceptibility of macrophages to Burkholderia cenocepacia infection and exacerbates IL-1β production157. Autophagy is further inhibited following treatment of patients with cystic fibrosis with the antibiotic azithromycin and is associated with increased infection by nontuberculous mycobacteria158. Thus, restoration of autophagy may ameliorate many chronic inflammatory disorders.

Conclusion

Autophagy and related processes regulate intracellular trafficking of pathogens, the production of inflammatory mediators and the viability of cells that coordinate immunity. Through these functions, the autophagy machinery controls complex multicellular immune responses at the whole organism level. The literature highlighted in this article reinforces three themes related to how these functions of autophagy are integrated into inflammatory signalling cascades to ensure an appropriate response to environmental threats and a return to homeostasis: one, pathways that induce autophagy are subject to regulation by autophagy; two, autophagy can increase or decrease different parts of the same inflammatory signalling cascade in a context-dependent manner; and three, non-canonical autophagy is pervasive. Although these principles apply to the role of autophagy across numerous physiological functions, they are perhaps most obvious in the recent literature examining the function of autophagy proteins in host defence and inflammatory disease.

These three themes have implications for the clinical application of autophagy inducers and inhibitors. Short-term induction of autophagy is effective in reducing the burden of intracellular pathogens16, and it can simultaneously enhance TLR-mediated cytokine production and antigen presentation by DCs to improve adaptive immunity138. Treating chronic infections is potentially more challenging and will require consideration of the bidirectional communication between autophagy and inflammation. It is important to bear in mind that the measure of an effective immune response is not how vigorous it is, but how efficiently the threat is neutralized without damaging the host. The successful application of therapeutic intervention may require knowledge of when the role of autophagy in reducing inflammation complements, rather than inhibits, the role of autophagy in reducing pathogen burden.

Treating complex inflammatory disorders by modulating autophagy has similar challenges. Before considering this strategy, it is important to identify the physiological situations in which the net effect of autophagy on the level of IL-1β, type I IFN and other cytokines is positive versus negative. Also, the cell types and organs most affected by autophagy activity should be determined. Although the discovery of non-canonical forms of autophagy has increased the complexity of the field, we may be able to exploit the subtle differences in the function of different components of the autophagy machinery. Indeed, deleting some autophagy genes in macrophages leads to a more pronounced inflammatory outcome than deleting other autophagy genes25,151, perhaps indicating that inhibition of certain parts of the pathway can be compensated by other membrane-trafficking processes, and/or that some autophagy proteins have partially redundant functions. It may be possible to target different nodes of the autophagy pathway without broadly affecting all the downstream immune functions of autophagy proteins.

Finally, defects in autophagy coincide with ageing, metabolic disease, cancer, myopathies and neurodegenerative disorders. Indeed, transgenic mice engineered to overexpress Atg5 display increased lifespan and improvements in glucose sensitivity and motor function159. If humans are to receive autophagy-based treatments for these conditions associated with ageing, it will be necessary to understand the effect of altered autophagy on inflammation, which universally accompanies maladies.

References

Russell, R. C. et al. ULK1 induces autophagy by phosphorylating Beclin-1 and activating VPS34 lipid kinase. Nat. Cell Biol. 15, 741–750 (2013).

Ge, L., Melville, D., Zhang, M. & Schekman, R. The ER-Golgi intermediate compartment is a key membrane source for the LC3 lipidation step of autophagosome biogenesis. eLife 2, e00947 (2013).

Hamasaki, M. et al. Autophagosomes form at ER-mitochondria contact sites. Nature 495, 389–393 (2013).

Dooley, H. C. et al. WIPI2 links LC3 conjugation with PI3P, autophagosome formation, and pathogen clearance by recruiting Atg12-5-16L1. Mol. Cell 55, 238–252 (2014).

Randow, F. & Youle, R. J. Self and nonself: how autophagy targets mitochondria and bacteria. Cell Host Microbe 15, 403–411 (2014).

Choy, A. et al. The Legionella effector RavZ inhibits host autophagy through irreversible Atg8 deconjugation. Science 338, 1072–1076 (2012).This study provides an example of how intracellular bacteria block autophagy to evade trafficking to the lysosome.

Chen, Y. H. et al. Phosphatidylserine vesicles enable efficient en bloc transmission of enteroviruses. Cell 160, 619–630 (2015).

Martinez, J. et al. Molecular characterization of LC3-associated phagocytosis reveals distinct roles for Rubicon, NOX2 and autophagy proteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 893–906 (2015).This study demonstrates that LAP is distinguished from autophagy by its dependence on rubicon and NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2).

Zhao, Z. et al. Autophagosome-independent essential function for the autophagy protein Atg5 in cellular immunity to intracellular pathogens. Cell Host Microbe 4, 458–469 (2008).

Hwang, S. et al. Nondegradative role of Atg5-Atg12/ Atg16L1 autophagy protein complex in antiviral activity of interferon gamma. Cell Host Microbe 11, 397–409 (2012).

Choi, J. et al. The parasitophorous vacuole membrane of Toxoplasma gondii is targeted for disruption by ubiquitin-like conjugation systems of autophagy. Immunity 40, 924–935 (2014).

Selleck, E. M. et al. A noncanonical autophagy pathway restricts Toxoplasma gondii growth in a strain-specific manner in IFN-γ activated human cells. mBio 6, e01157–e01115 (2015).

Ohshima, J. et al. Role of mouse and human autophagy proteins in IFN-γ-induced cell-autonomous responses against Toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol. 192, 3328–3335 (2014).

Haldar, A. K., Piro, A. S., Pilla, D. M., Yamamoto, M. & Coers, J. The E2-like conjugation enzyme Atg3 promotes binding of IRG and Gbp proteins to Chlamydia- and Toxoplasma-containing vacuoles and host resistance. PLoS ONE 9, e86684 (2014).

Park, S. et al. Targeting by Autophagy proteins (TAG): targeting of IFNγ-inducible GTPases to membranes by the LC3 conjugation system of autophagy. Autophagy 12, 1153–1167 (2016).

Shoji-Kawata, S. et al. Identification of a candidate therapeutic autophagy-inducing peptide. Nature 494, 201–206 (2013).This study shows that a cell-permeable beclin 1 peptide induces autophagy to enhance host defence.

Orvedahl, A. et al. Autophagy protects against Sindbis virus infection of the central nervous system. Cell Host Microbe 7, 115–127 (2010).

Kernbauer, E., Ding, Y. & Cadwell, K. An enteric virus can replace the beneficial function of commensal bacteria. Nature 516, 94–98 (2014).

Cadwell, K. et al. Virus-plus-susceptibility gene interaction determines Crohn's disease gene Atg16L1 phenotypes in intestine. Cell 141, 1135–1145 (2010).

Visvikis, O. et al. Innate host defense requires TFEB-mediated transcription of cytoprotective and antimicrobial genes. Immunity 40, 896–909 (2014).

Maurer, K. et al. Autophagy mediates tolerance to Staphylococcus aureus α-toxin. Cell Host Microbe 17, 429–440 (2015).This study shows that autophagy limits damage caused by a pore-forming toxin from a clinical isolate of S. aureus.

Figueiredo, N. et al. Anthracyclines induce DNA damage response-mediated protection against severe sepsis. Immunity 39, 874–884 (2013).

Medzhitov, R., Schneider, D. S. & Soares, M. P. Disease tolerance as a defense strategy. Science 335, 936–941 (2012).

Marchiando, A. M. et al. A deficiency in the autophagy gene Atg16L1 enhances resistance to enteric bacterial infection. Cell Host Microbe 14, 216–224 (2013).

Park, S. et al. Autophagy genes enhance murine gammaherpesvirus 68 reactivation from latency by preventing virus-induced systemic inflammation. Cell Host Microbe 19, 91–101 (2016).

Lu, Q. et al. Homeostatic control of innate lung inflammation by vici syndrome gene Epg5 and additional autophagy genes promotes influenza pathogenesis. Cell Host Microbe 19, 102–113 (2016).

Tattoli, I. et al. Amino acid starvation induced by invasive bacterial pathogens triggers an innate host defense program. Cell Host Microbe 11, 563–575 (2012).

Saitoh, T. et al. Loss of the autophagy protein Atg16L1 enhances endotoxin-induced IL-1β production. Nature 456, 264–268 (2008).This study is the first to demonstrate the immunosuppressive function of autophagy in limiting inflammasome activation.

Nakahira, K. et al. Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat. Immunol. 12, 222–230 (2011).

Zhong, Z. et al. NF-κB restricts inflammasome activation via elimination of damaged mitochondria. Cell 164, 896–910 (2016).This study shows that mitophagy inhibits inflammasome activation in the presence of LPS.

Dupont, N. et al. Shigella phagocytic vacuolar membrane remnants participate in the cellular response to pathogen invasion and are regulated by autophagy. Cell Host Microbe 6, 137–149 (2009).

Meunier, E. et al. Caspase-11 activation requires lysis of pathogen-containing vacuoles by IFN-induced GTPases. Nature 509, 366–370 (2014).

Kreibich, S. et al. Autophagy proteins promote repair of endosomal membranes damaged by the Salmonella type three secretion system 1. Cell Host Microbe 18, 527–537 (2015).

Suzuki, T. et al. Differential regulation of caspase-1 activation, pyroptosis, and autophagy via Ipaf and ASC in Shigella-infected macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 3, e111 (2007).

Byrne, B. G., Dubuisson, J. F., Joshi, A. D., Persson, J. J. & Swanson, M. S. Inflammasome components coordinate autophagy and pyroptosis as macrophage responses to infection. mBio 4, e00620–00612 (2013).

Shi, C. S. et al. Activation of autophagy by inflammatory signals limits IL-1β production by targeting ubiquitinated inflammasomes for destruction. Nat. Immunol. 13, 255–263 (2012).

Bodemann, B. O. et al. RalB and the exocyst mediate the cellular starvation response by direct activation of autophagosome assembly. Cell 144, 253–267 (2011).

Ravindran, R. et al. The amino acid sensor GCN2 controls gut inflammation by inhibiting inflammasome activation. Nature 531, 523–527 (2016).

Wlodarska, M. et al. NLRP6 inflammasome orchestrates the colonic host-microbial interface by regulating goblet cell mucus secretion. Cell 156, 1045–1059 (2014).

Travassos, L. H. et al. Nod1 and Nod2 direct autophagy by recruiting ATG16L1 to the plasma membrane at the site of bacterial entry. Nat. Immunol. 11, 55–62 (2010).

Cooney, R. et al. NOD2 stimulation induces autophagy in dendritic cells influencing bacterial handling and antigen presentation. Nat. Med. 16, 90–97 (2010).

Homer, C. R. et al. A dual role for receptor-interacting protein kinase 2 (RIP2) kinase activity in nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2 (NOD2)-dependent autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 25565–25576 (2012).

Anand, P. K. et al. TLR2 and RIP2 pathways mediate autophagy of Listeria monocytogenes via extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 42981–42991 (2011).

Irving, A. T. et al. The immune receptor NOD1 and kinase RIP2 interact with bacterial peptidoglycan on early endosomes to promote autophagy and inflammatory signaling. Cell Host Microbe 15, 623–635 (2014).

Chauhan, S., Mandell, M. A. & Deretic, V. IRGM governs the core autophagy machinery to conduct antimicrobial defense. Mol. Cell 58, 507–521 (2015).

Plantinga, T. S. et al. Crohn's disease-associated ATG16L1 polymorphism modulates pro-inflammatory cytokine responses selectively upon activation of NOD2. Gut 60, 1229–1235 (2011).

Buffen, K. et al. Autophagy modulates Borrelia burgdorferi-induced production of interleukin-1β (IL-1β). J. Biol. Chem. 288, 8658–8666 (2013).

Lassen, K. G. et al. Atg16L1 T300A variant decreases selective autophagy resulting in altered cytokine signaling and decreased antibacterial defense. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 7741–7746 (2014).

Murthy, A. et al. A Crohn's disease variant in Atg16l1 enhances its degradation by caspase 3. Nature 506, 456–462 (2014).

Lupfer, C. et al. Receptor interacting protein kinase 2-mediated mitophagy regulates inflammasome activation during virus infection. Nat. Immunol. 14, 480–488 (2013).

Wen, Z. et al. Neutrophils counteract autophagy-mediated anti-inflammatory mechanisms in alveolar macrophage: role in posthemorrhagic shock acute lung inflammation. J. Immunol. 193, 4623–4633 (2014).

Chu, H. et al. Gene-microbiota interactions contribute to the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Science 352, 1116–1120 (2016).

Xu, Y. et al. Toll-like receptor 4 is a sensor for autophagy associated with innate immunity. Immunity 27, 135–144 (2007).

Delgado, M. A., Elmaoued, R. A., Davis, A. S., Kyei, G. & Deretic, V. Toll-like receptors control autophagy. EMBO J. 27, 1110–1121 (2008).

Shi, C. S. & Kehrl, J. H. TRAF6 and A20 regulate lysine 63-linked ubiquitination of Beclin-1 to control TLR4-induced autophagy. Sci. Signal. 3, ra42 (2010).

Meijer, A. H. & van der Vaart, M. DRAM1 promotes the targeting of mycobacteria to selective autophagy. Autophagy 10, 2389–2391 (2014).

Fujita, K., Maeda, D., Xiao, Q. & Srinivasula, S. M. Nrf2-mediated induction of p62 controls Toll-like receptor-4-driven aggresome-like induced structure formation and autophagic degradation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 1427–1432 (2011).

Wild, P. et al. Phosphorylation of the autophagy receptor optineurin restricts Salmonella growth. Science 333, 228–233 (2011).

Moy, R. H. et al. Antiviral autophagy restricts Rift Valley fever virus infection and is conserved from flies to mammals. Immunity 40, 51–65 (2014).

Benjamin, J. L., Sumpter, R. Jr., Levine, B. & Hooper, L. V. Intestinal epithelial autophagy is essential for host defense against invasive bacteria. Cell Host Microbe 13, 723–734 (2013).

Lee, H. K., Lund, J. M., Ramanathan, B., Mizushima, N. & Iwasaki, A. Autophagy-dependent viral recognition by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Science 315, 1398–1401 (2007).

Henault, J. et al. Noncanonical autophagy is required for type I interferon secretion in response to DNA-immune complexes. Immunity 37, 986–997 (2012).

Sanjuan, M. A. et al. Toll-like receptor signalling in macrophages links the autophagy pathway to phagocytosis. Nature 450, 1253–1257 (2007).

Akoumianaki, T. et al. Aspergillus cell wall melanin blocks LC3-associated phagocytosis to promote pathogenicity. Cell Host Microbe 19, 79–90 (2016).

Katsuragi, Y. Ichimura, Y. & Komatsu, M. p62/SQSTM1 functions as a signaling hub and an autophagy adaptor. FEBS J. 282, 4672–4678 (2015).

Lee, H. M. et al. Autophagy negatively regulates keratinocyte inflammatory responses via scaffolding protein p62/SQSTM1. J. Immunol. 186, 1248–1258 (2011).

Kim, J. K. et al. MicroRNA-125a inhibits autophagy activation and antimicrobial responses during mycobacterial infection. J. Immunol. 194, 5355–5365 (2015).

Lei, Y. et al. The mitochondrial proteins NLRX1 and TUFM form a complex that regulates type I interferon and autophagy. Immunity 36, 933–946 (2012).

Xia, M. et al. Mitophagy enhances oncolytic measles virus replication by mitigating DDX58/RIG-I-like receptor signaling. J. Virol. 88, 5152–5164 (2014).

Zhao, Y. et al. COX5B regulates MAVS-mediated antiviral signaling through interaction with ATG5 and repressing ROS production. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1003086 (2012).

Tal, M. C. et al. Absence of autophagy results in reactive oxygen species-dependent amplification of RLR signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 2770–2775 (2009).

Jounai, N. et al. The Atg5–Atg12 conjugate associates with innate antiviral immune responses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 14050–14055 (2007).

Saitoh, T. et al. Atg9a controls dsDNA-driven dynamic translocation of STING and the innate immune response. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 20842–20846 (2009).

Konno, H., Konno, K. & Barber, G. N. Cyclic dinucleotides trigger ULK1 (ATG1) phosphorylation of STING to prevent sustained innate immune signaling. Cell 155, 688–698 (2013).

Liang, Q. et al. Crosstalk between the cGAS DNA sensor and Beclin-1 autophagy protein shapes innate antimicrobial immune responses. Cell Host Microbe 15, 228–238 (2014).

Lan, Y. Y., Londono, D., Bouley, R., Rooney, M. S. & Hacohen, N. Dnase2a deficiency uncovers lysosomal clearance of damaged nuclear DNA via autophagy. Cell Rep. 9, 180–119 (2014).

Mathew, R. et al. Functional role of autophagy-mediated proteome remodeling in cell survival signaling and innate immunity. Mol. Cell 55, 916–930 (2014).

Grimm, W. A. et al. The Thr300Ala variant in ATG16L1 is associated with improved survival in human colorectal cancer and enhanced production of type I interferon. Gut 65, 456–464 (2016).

Gutierrez, M. G. et al. Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell 119, 753–766 (2004).

Harris, J. et al. T helper 2 cytokines inhibit autophagic control of intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Immunity 27, 505–517 (2007).

Mostowy, S. et al. p62 and NDP52 proteins target intracytosolic Shigella and Listeria to different autophagy pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 26987–26995 (2011).

Matsuzawa, T. et al. IFN-γ elicits macrophage autophagy via the p38 MAPK signaling pathway. J. Immunol. 189, 813–818 (2012).

Chang, Y. P. et al. Autophagy facilitates IFN-γ-induced Jak2-STAT1 activation and cellular inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 28715–28722 (2010).

Boonhok, R. et al. LAP-like process as an immune mechanism downstream of IFN-γ in control of the human malaria Plasmodium vivax liver stage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E3519–E3528 (2016).

Shen, S. et al. Cytoplasmic STAT3 represses autophagy by inhibiting PKR activity. Mol. Cell 48, 667–680 (2012).

Van Grol, J. et al. HIV-1 inhibits autophagy in bystander macrophage/monocytic cells through Src-Akt and STAT3. PLoS ONE 5, e11733 (2010).

Terawaki, S. et al. RUN and FYVE domain-containing protein 4 enhances autophagy and lysosome tethering in response to Interleukin-4. J. Cell Biol. 210, 1133–1152 (2015).

Dupont, N. et al. Autophagy-based unconventional secretory pathway for extracellular delivery of IL-1β. EMBO J. 30, 4701–4711 (2011).

Cullen, S. P., Kearney, C. J., Clancy, D. M. & Martin, S. J. Diverse activators of the NLRP3 inflammasome promote IL-1β secretion by triggering necrosis. Cell Rep. 11, 1535–1548 (2015).

Zhang, M., Kenny, S., Ge, L., Xu, K. & Schekman, R. Translocation of interleukin-1β into a vesicle intermediate in autophagy-mediated secretion. eLife 4, e11205 (2015).

Pilli, M. et al. TBK-1 promotes autophagy-mediated antimicrobial defense by controlling autophagosome maturation. Immunity 37, 223–234 (2012).

Castillo, E. F. et al. Autophagy protects against active tuberculosis by suppressing bacterial burden and inflammation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, E3168–E3176 (2012).

Lee, J. P. et al. Loss of autophagy enhances MIF/macrophage migration inhibitory factor release by macrophages. Autophagy 12, 907–916 (2016).

Peral de Castro, C. et al. Autophagy regulates IL-23 secretion and innate T cell responses through effects on IL-1 secretion. J. Immunol. 189, 4144–4153 (2012).

Ding, Y. et al. Autophagy regulates TGF-β expression and suppresses kidney fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 25, 2835–2846 (2014).

Trinchieri, G. Type I interferon: friend or foe? J. Exp. Med. 207, 2053–2063 (2010).

Mello Pde, A. et al. Adenosine uptake is the major effector of extracellular ATP toxicity in human cervical cancer cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 2905–2918 (2014).

Biswas, D. et al. ATP-induced autophagy is associated with rapid killing of intracellular mycobacteria within human monocytes/macrophages. BMC Immunol. 9, 35 (2008).

Takenouchi, T. et al. The activation of P2X7 receptor impairs lysosomal functions and stimulates the release of autophagolysosomes in microglial cells. J. Immunol. 182, 2051–2062 (2009).

Bian, S. et al. P2X7 integrates PI3K/AKT and AMPK-PRAS40-mTOR signaling pathways to mediate tumor cell death. PLoS ONE 8, e60184 (2013).

Martins, I. et al. Molecular mechanisms of ATP secretion during immunogenic cell death. Cell Death Differ. 21, 79–91 (2014).

Michaud, M. et al. Autophagy-dependent anticancer immune responses induced by chemotherapeutic agents in mice. Science 334, 1573–1577 (2011).This study demonstrates that autophagy promotes antitumour immunity by mediating the release of ATP.

Tang, D. et al. Endogenous HMGB1 regulates autophagy. J. Cell Biol. 190, 881–892 (2010).

Kang, R. et al. The receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) sustains autophagy and limits apoptosis, promoting pancreatic tumor cell survival. Cell Death Differ. 17, 666–676 (2010).

Tang, D. et al. High-mobility group box 1 is essential for mitochondrial quality control. Cell. Metabolism 13, 701–711 (2011).

Zhu, X. et al. Cytosolic HMGB1 controls the cellular autophagy/apoptosis checkpoint during inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 1098–1110 (2015).

Yanai, H. et al. Conditional ablation of HMGB1 in mice reveals its protective function against endotoxemia and bacterial infection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 20699–20704 (2013).

Pua, H. H., Dzhagalov, I., Chuck, M., Mizushima, N. & He, Y. W. A critical role for the autophagy gene Atg5 in T cell survival and proliferation. J. Exp. Med. 204, 25–31 (2007).This study is the first to demonstrate that deficiency in an autophagy protein leads to defects in lymphocyte survival and proliferation.

Stephenson, L. M. et al. Identification of Atg5-dependent transcriptional changes and increases in mitochondrial mass in Atg5-deficient T lymphocytes. Autophagy 5, 625–635 (2009).

Jia, W. & He, Y. W. Temporal regulation of intracellular organelle homeostasis in T lymphocytes by autophagy. J. Immunol. 186, 5313–5322 (2011).

Kovacs, J. R. et al. Autophagy promotes T-cell survival through degradation of proteins of the cell death machinery. Cell Death Differ. 19, 144–152 (2012).

Pei, B. et al. Invariant NKT cells require autophagy to coordinate proliferation and survival signals during differentiation. J. Immunol. 194, 5872–5884 (2015).

Willinger, T. & Flavell, R. A. Canonical autophagy dependent on the class III phosphoinositide-3 kinase Vps34 is required for naive T-cell homeostasis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 8670–8675 (2012).

Matsuzawa, Y. et al. TNFAIP3 promotes survival of CD4 T cells by restricting MTOR and promoting autophagy. Autophagy 11, 1052–1062 (2015).

Xu, X. et al. Autophagy is essential for effector CD8+ T cell survival and memory formation. Nat. Immunol. 15, 1152–1161 (2014).

O'Sullivan, T. E., Johnson, L. R., Kang, H. H. & Sun, J. C. BNIP3- and BNIP3L-mediated mitophagy promotes the generation of natural killer cell memory. Immunity 43, 331–342 (2015).

Puleston, D. J. et al. Autophagy is a critical regulator of memory CD8+ T cell formation. eLife 3, e03706 (2014).

Schlie, K. et al. Survival of effector CD8+ T cells during influenza infection is dependent on autophagy. J. Immunol. 194, 4277–4286 (2015).

Henson, S. M. et al. p38 signaling inhibits mTORC1-independent autophagy in senescent human CD8+ T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 4004–4016 (2014).

Hubbard, V. M. et al. Macroautophagy regulates energy metabolism during effector T cell activation. J. Immunol. 185, 7349–7357 (2010).

Miller, B. C. et al. The autophagy gene ATG5 plays an essential role in B lymphocyte development. Autophagy 4, 309–314 (2008).

Conway, K. L. et al. ATG5 regulates plasma cell differentiation. Autophagy 9, 528–537 (2013).

Pengo, N. et al. Plasma cells require autophagy for sustainable immunoglobulin production. Nat. Immunol. 14, 298–305 (2013).

Paul, S., Kashyap, A. K., Jia, W., He, Y. W. & Schaefer, B. C. Selective autophagy of the adaptor protein Bcl10 modulates T cell receptor activation of NF-κB. Immunity 36, 947–958 (2012).

Wei, J. et al. Autophagy enforces functional integrity of regulatory T cells by coupling environmental cues and metabolic homeostasis. Nat. Immunol. 17, 277–285 (2016).

Kabat, A. M. et al. The autophagy gene Atg16l1 differentially regulates Treg and TH2 cells to control intestinal inflammation. eLife 5, de12444 (2016).

Dengjel, J. et al. Autophagy promotes MHC class II presentation of peptides from intracellular source proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 7922–7927 (2005).

Nedjic, J., Aichinger, M., Emmerich, J., Mizushima, N. & Klein, L. Autophagy in thymic epithelium shapes the T-cell repertoire and is essential for tolerance. Nature 455, 396–400 (2008).

Ireland, J. M. & Unanue, E. R. Autophagy in antigen-presenting cells results in presentation of citrullinated peptides to CD4 T cells. J. Exp. Med. 208, 2625–2632 (2011).

Paludan, C. et al. Endogenous MHC class II processing of a viral nuclear antigen after autophagy. Science 307, 593–596 (2005).

Lee, Y. et al. p62 plays a specific role in interferon-γ-induced presentation of a Toxoplasma vacuolar antigen. Cell Rep. 13, 223–233 (2015).

Sakowski, E. T. et al. Ubiquilin 1 promotes IFN-γ-induced xenophagy of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005076 (2015).

Romao, S. et al. Autophagy proteins stabilize pathogen-containing phagosomes for prolonged MHC II antigen processing. J. Cell Biol. 203, 757–766 (2013).

Martinez, J. et al. Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 alpha (LC3)-associated phagocytosis is required for the efficient clearance of dead cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 17396–17401 (2011).

Brooks, C. R. et al. KIM-1-/TIM-1-mediated phagocytosis links ATG5-/ULK1-dependent clearance of apoptotic cells to antigen presentation. EMBO J. 34, 2441–2464 (2015).

Lee, H. K. et al. In vivo requirement for Atg5 in antigen presentation by dendritic cells. Immunity 32, 227–239 (2010).This study demonstrates that the autophagy pathway in DCs is crucial for antigen presentation during herpesvirus infection in vivo.

Gobeil, P. A. & Leib, D. A. Herpes simplex virus gamma34.5 interferes with autophagosome maturation and antigen presentation in dendritic cells. mBio 3, e00267–00212 (2012).

Ravindran, R. et al. Vaccine activation of the nutrient sensor GCN2 in dendritic cells enhances antigen presentation. Science 343, 313–317 (2014).This study shows that autophagy induced by the nutrient sensor GCN2 promotes cross-presentation of viral antigens.

Jostins, L. et al. Host–microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 491, 119–124 (2012).

Cadwell, K. et al. A key role for autophagy and the autophagy gene Atg16l1 in mouse and human intestinal Paneth cells. Nature 456, 259–263 (2008).This study identifies a role for the autophagy gene ATG16L1 in supporting intestinal Paneth cells.

Patel, K. K. et al. Autophagy proteins control goblet cell function by potentiating reactive oxygen species production. EMBO J. 32, 3130–3144 (2013).

Adolph, T. E. et al. Paneth cells as a site of origin for intestinal inflammation. Nature 503, 272–276 (2013).

Conway, K. L. et al. Atg16l1 is required for autophagy in intestinal epithelial cells and protection of mice from Salmonella infection. Gastroenterology 145, 1347–1357 (2013).

Hubbard-Lucey, V. M. et al. Autophagy gene atg16l1 prevents lethal T cell alloreactivity mediated by dendritic cells. Immunity 41, 579–591 (2014).

Martin, L. J. et al. Functional variant in the autophagy-related 5 gene promotor is associated with childhood asthma. PLoS ONE 7, e33454 (2012).

Zhou, X. J. et al. Genetic association of PRDM1- ATG5 intergenic region and autophagy with systemic lupus erythematosus in a Chinese population. Ann. Rheumat. Diseases 70, 1330–1337 (2011).

Dickinson, J. D. et al. IL13 activates autophagy to regulate secretion in airway epithelial cells. Autophagy 12, 397–409 (2015).

Clarke, A. J. et al. Autophagy is activated in systemic lupus erythematosus and required for plasmablast development. Ann. Rheumat. Diseases 74, 912–920 (2015).

Alessandri, C. et al. T lymphocytes from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus are resistant to induction of autophagy. FASEB J. 26, 4722–4732 (2012).

Weindel, C. G. et al. B cell autophagy mediates TLR7-dependent autoimmunity and inflammation. Autophagy 11, 1010–1024 (2015).