Abstract

Migraine is a disabling primary headache disorder that directly affects more than one billion people worldwide. Despite its widespread prevalence, migraine remains under-diagnosed and under-treated. To support clinical decision-making, we convened a European panel of experts to develop a ten-step approach to the diagnosis and management of migraine. Each step was established by expert consensus and supported by a review of current literature, and the Consensus Statement is endorsed by the European Headache Federation and the European Academy of Neurology. In this Consensus Statement, we introduce typical clinical features, diagnostic criteria and differential diagnoses of migraine. We then emphasize the value of patient centricity and patient education to ensure treatment adherence and satisfaction with care provision. Further, we outline best practices for acute and preventive treatment of migraine in various patient populations, including adults, children and adolescents, pregnant and breastfeeding women, and older people. In addition, we provide recommendations for evaluating treatment response and managing treatment failure. Lastly, we discuss the management of complications and comorbidities as well as the importance of planning long-term follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Migraine is a highly disabling primary headache disorder with a 1-year prevalence of ~15% in the general population1,2. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study, migraine is the second most prevalent neurological disorder worldwide and is responsible for more disability than all other neurological disorders combined2,3.

Migraine manifests clinically as recurrent attacks of headache with a range of accompanying symptoms4. In approximately one third of individuals with migraine, headache is sometimes or always preceded or accompanied by transient neurological disturbances, referred to as migraine aura5,6. Furthermore, a minority of those affected develop chronic migraine, in which attacks become highly frequent7. The pathogenesis of migraine is widely believed to involve peripheral and central activation of the trigeminovascular system8, and cortical spreading depression is thought to be the underlying neurophysiological substrate of migraine aura9. However, much remains unknown about specific pathogenic processes and few mechanism-based treatment options currently exist10.

Treatments for migraine include acute and preventive medications and a range of non-pharmacological therapies10. Despite these treatment options and the comprehensive diagnostic criteria, clinical care remains suboptimal — misdiagnosis and under-treatment of migraine are substantial public health challenges11,12. Population-based data from Europe indicate that preventive medication for migraine is used by only 2–14% of eligible individuals11, an alarming finding that calls for global action12. A comprehensive approach is needed to facilitate accurate diagnosis and evidence-based management.

In this Consensus Statement, we provide a ten-step approach to the diagnosis and management of migraine (Fig. 1). Development of this approach was initiated by the Danish Headache Society, and the Consensus Statement is endorsed by the European Headache Federation (EHF) and the European Academy of Neurology (EAN). The aim of the approach is to support care and clinical decision-making by primary care practitioners, neurologists and headache specialists alike.

Methods

The Danish Headache Society and its representatives (A.K.E., H.A., H.W.S. and M.Ashina) conceived a European Consensus Statement on the diagnosis and clinical management of migraine. A formal proposal, including a suggested list of authors, was prepared and submitted to the Board of Directors of the EHF, the Chairs of the EAN Headache Panel and the Chair of the EAN Scientific Committee. The proposal was approved by unanimous decision and a European expert panel was convened to develop this Consensus Statement. Three authors (H.A., T.J.S. and M.Ashina) identified the ten most important steps in diagnosis and management of migraine through email correspondence. Once these steps were agreed, seven authors (A.K.E., H.A., S.K., H.-C.D., H.W.S., T.J.S. and M.Ashina) wrote the initial draft.

For each of the ten steps, a structured literature search was performed in April 2021 using the PubMed database. We searched for “migraine” in combination with the terms “diagnosis”, “treatment”, “therapies”, “treatment outcome” or “prognosis”. We excluded publications written in a language other than English. We also selected additional articles deemed relevant from a search of the reference lists of the originally identified articles. The content was targeted towards a broad readership of primary care practitioners, neurologists and headache specialists.

In continuous email correspondence, all authors reviewed the initial draft and contributed to all subsequent drafts. Whenever possible, recommendations were based on interpretation of findings from systematic reviews and meta-analyses, relying on expert opinion only when scientific evidence was limited or unavailable. The views of each author were taken fully into consideration and revisions were made until unanimous consensus was reached. Four rounds of review were required to establish consensus.

Step 1: When to suspect migraine

In the third edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3), migraine is classified into three main types4: migraine without aura, migraine with aura, and chronic migraine. The clinical characteristics of each must be considered to ensure an accurate diagnosis.

Migraine without aura

Migraine without aura is characterized by recurrent headache attacks that last 4–72 h4. Typical features of an attack include a unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, and aggravation by routine physical activity4,13. However, bilateral pain is not uncommon; population-based data indicate that ~40% of individuals with migraine report bilateral pain during attacks5. The most common associated symptoms are photophobia, phonophobia, nausea and vomiting4,13. Before the onset of pain, prodromal symptoms can include a depressed mood, yawning, fatigue and cravings for specific foods14. After resolution of the headache, postdromal symptoms can last up to 48 h and often include tiredness, concentration difficulties and neck stiffness15.

Migraine with aura

Approximately one third of individuals with migraine experience aura5, either with every attack or with some attacks. Aura is defined as transient focal neurological symptoms that usually precede, but sometimes accompany, the headache phase of a migraine attack4. In >90% of affected individuals, aura manifests visually4,16, classically as fortification spectra4. Sensory symptoms occur in ~31% of affected individuals and are usually experienced as predominantly unilateral paraesthesia (pins and needles and/or numbness) that spreads gradually in the face or arm16.

Less common aura symptoms include aphasic speech disturbance, brainstem symptoms (such as dysarthria and vertigo), motor weakness (in hemiplegic migraine) and retinal symptoms (for example, repeated monocular visual disturbances)4. Aura symptoms can be similar to those of transient ischaemic attacks (TIA), but can be differentiated on the basis that aura symptoms often spread gradually (over ≥5 min) and occur in succession, whereas symptoms of a TIA have a sudden, simultaneous onset4.

Notably, migraine with aura and migraine without aura can coexist. Many individuals with migraine with aura also experience attacks that are not preceded by aura4. In such cases, migraine with aura and migraine without aura should both be diagnosed.

Chronic migraine

Chronic migraine is defined as ≥15 headache days per month for >3 months and fulfilment of ICHD-3 criteria for migraine on ≥8 days per month4. Chronic migraine is not a static entity and reversion to episodic migraine is not unusual. Similarly, retransformation to chronic migraine can subsequently occur17.

Family history of migraine

Migraine has a strong genetic component and its prevalence is higher among people with directly affected first-degree relatives than among the general population18,19. Family history is, therefore, an important part of the medical history and is often positive in patients with migraine, although it might be under-reported by patients20.

Recommendations

-

Suspect migraine without aura in a person with recurrent moderate to severe headache, particularly if pain is unilateral and/or pulsating, and when the person has accompanying symptoms such as photophobia, phonophobia, nausea and/or vomiting.

-

Suspect migraine with aura in a person with the symptoms above and recurrent, short-lasting visual and/or hemisensory disturbances.

-

Suspect chronic migraine in a person with ≥15 headache days per month.

-

Suspicion of migraine should be strengthened by a family history of migraine and if onset of symptoms is at or around puberty.

Step 2: Diagnosis of migraine

The medical history is the mainstay of migraine diagnosis; with the assistance of a range of published aids (see the section Diagnostic aids), a full history should enable systematic application of the criteria set out in the ICHD-3. Physical examination is most often confirmatory and further investigations (for example, neuroimaging, blood samples or lumbar puncture) are occasionally required to confirm or reject suspicions of secondary causes for headache.

Medical history

An adequate medical history must include at least the following: age at onset of headache; duration of headache episodes; frequency of headache episodes; pain characteristics (for example, location, quality, severity, aggravating factors and relieving factors); accompanying symptoms (for example, photophobia, phonophobia, nausea and vomiting); aura symptoms (if any); and history of acute and preventive medication use. All are essential for the application of the ICHD-3 criteria.

Diagnostic criteria

The ICHD-3 criteria4 (Box 1), which were developed by the International Headache Society, set out the clinical features that establish the diagnosis of migraine and its types and subtypes. These criteria prioritize specificity over sensitivity, so an additional set of criteria are given for a diagnosis of probable migraine, which is defined as “migraine-like attacks missing one of the features required to fulfil all criteria for a type or subtype of migraine”4. Probable migraine is a diagnosis pending confirmation during early follow-up.

Diagnostic aids

Headache diaries are useful diagnostic aids that can also be used to re-evaluate the diagnosis whenever needed (Box 2). Daily diary entries record information on the pattern and frequency of headaches and its accompanying symptoms (for example, nausea, photophobia and phonophobia), as well as use of acute medications (Box 2). Diaries should not be conflated with headache calendars, which typically include less information but are useful in the follow-up assessment of patients. Headache calendars should be used to record, at minimum, the frequency of migraine, the frequency and intensity of headaches, and headache-related events, such as acute and preventive medication use and menstruation (Box 2).

The emergence and refinement of electronic headache diaries and calendars are important developments, as these are likely to facilitate acquisition of more detailed information without markedly compromising compliance. Compliance with headache diaries can be an issue, particularly in primary care; for example, in one population-based study of patients who reported frequent headaches, only 46% of participants completed the study21.

Diagnosis of migraine can also be facilitated by use of screening instruments that evaluate whether a patient’s clinical features suggest migraine (Box 2). After use of such screening instruments, diagnosis should be confirmed by a review of the medical history and/or use of a diagnostic headache diary. Validated screening instruments include the three-item ID-Migraine questionnaire22 and the five-item Migraine Screen Questionnaire (MS-Q)23. The ID-Migraine questionnaire has a sensitivity of 0.81, a specificity of 0.75 and a positive predictive value of 0.93 when compared with ICHD-based diagnosis by a headache specialist22. The MS-Q instrument has a sensitivity of 0.93, a specificity of 0.81 and a positive predictive value of 0.83 (ref.23). Both instruments have been translated and validated for use in several languages24,25,26,27.

Differential diagnoses

Differential diagnoses for migraine include other primary headache disorders (Table 1) and some secondary headache disorders (Table 2). Distinction from other primary headache disorders is a prerequisite for successful management, whereas distinction from secondary headache disorders is crucial because some of these disorders are serious and potentially life-threatening (for example, meningitis and subarachnoid haemorrhage) (Table 2).

Tension-type headache (TTH) is the only other paroxysmal headache disorder that is prevalent in the general population28. TTH lacks the symptoms that accompany migraine and usually involves bilateral, mild to moderate pain with a pressing or tightening quality that is not aggravated by routine physical activity4,28 (Table 1).

Cluster headache is a much less prevalent primary headache disorder that affects ~0.1% of the general population29. Its features are highly characteristic and include frequently recurrent but short-lasting attacks (15–180 min) of strictly unilateral headache of severe or very severe intensity4. The head pain is accompanied by ipsilateral cranial autonomic symptoms, such as conjunctival injection, lacrimation and nasal congestion4 (Table 1).

Medication-overuse headache (MOH) is a secondary headache disorder that is an important differential diagnosis for chronic migraine30 (Box 1). This disorder commonly develops from overuse of acute medication to treat migraine attacks, so the two disorders are often conflated (see Step 8 for more on MOH).

Some other secondary headache disorders can present with features that suggest migraine, but specific red flags should create suspicion (Table 2). Red flags in the medical history include thunderclap headache, atypical aura and head trauma. Red flags in the physical examination include unexplained fever, impaired memory and focal neurological symptoms (Table 2). These red flags are indications for further investigation, such as neuroimaging, blood samples or lumbar puncture31.

Need for neuroimaging

The only role for neuroimaging in the diagnosis of headache is to confirm or exclude causes of secondary headache that are suspected on the basis of red flags in the medical history and/or physical examination32,33. Otherwise, neuroimaging is not only rarely necessary in the diagnostic work-up of migraine but can be harmful, as it can involve exposure to ionizing radiation33,34. When needed for investigation of possible secondary headache disorders, MRI is preferred to CT, as it offers a higher resolution and does not involve exposure to ionizing radiation35,36. However, MRI can reveal clinically insignificant abnormalities (for example, white matter lesions, arachnoid cysts and meningiomas), which can alarm the patient and lead to further unnecessary testing33,37,38.

Recommendations

-

Take a careful medical history, applying the ICHD-3 criteria.

-

Use validated diagnostic aids and screening tools, such as headache diaries, the three-item ID-Migraine questionnaire and the five-item Migraine Screen Questionnaire.

-

Consider differential diagnoses, including other primary headache disorders and secondary headache disorders.

-

Use neuroimaging only when a secondary headache disorder is suspected.

Step 3: Education and patient centricity

Patient centricity and education have important roles in the management of migraine. Indeed, optimal outcomes are unlikely when these aspects are not given sufficient attention.

Explanation, reassurance and objectives

Patient satisfaction is a key management outcome and treatment success depends on it but most people with migraine report at least one perceived unmet treatment need39. Unrealistic expectations constitute a major obstacle to achieving patient satisfaction — a common misconception among patients is that effective treatment means cure of their migraine32,40. Clinicians must therefore disabuse patients of this belief without being overly negative. A realistic objective is a return of control from the disease to the patient with treatment that mitigates attack-related disability (by reducing attack frequency, attack duration and/or pain intensity) to an extent that the patient can continue with life with as little hindrance as possible.

Non-adherence is also an obstacle to effective treatment41 and requires management. Education is the solution — clinicians must explain to the patient both the disease and the principles of managing it effectively, including instruction on the correct use of medication, potential adverse effects and what to do about them, and the importance of avoiding medication overuse. Such education can require time that is not available, but freely available patient information leaflets can support patient education32.

Predisposing factors and triggers

Contrary to popular belief, predisposing and trigger factors are of limited importance in migraine, and their role is often overemphasized42. An important exception is menstruation, as some women’s migraine attacks are exclusively or frequently menstruation-related. True trigger factors are often self-evident. Moreover, aggravating factors should not be conflated with predisposing factors. The former worsen headache during migraine attacks (for example, physical activity), whereas predisposing factors increase susceptibility to the development of a migraine attack (for example, poor sleep quality, poor physical fitness or stress).

Nevertheless, if predisposing and trigger factors can be correctly identified and subsequently avoided (which is often not possible), some headache control might be achievable without further intervention43. For instance, lifestyle changes can benefit patients with poor sleep quality or physical fitness, though any changes should not result in unnecessary avoidance behaviour, which can itself damage quality of life.

Individualized therapy

Multiple effective acute and preventive therapies are available for migraine. When selecting from these therapies, the objective is that each patient receives the therapy that provides the best personal outcome. Unfortunately, no a priori basis for selection currently exists, at least for acute therapy. Optimal individualized therapy is therefore currently best achieved with a stepped care approach, set out in detail in Step 4.

Recommendations

-

Provide every patient with a full explanation of migraine as a disease and of the principles of its management.

-

Consider predisposing and trigger factors, but keep in mind that true trigger factors are often self-evident.

-

Adhere to the principles of stepped care to achieve optimal individualized therapy (see Step 4).

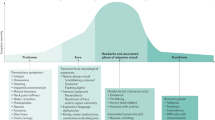

Step 4: Acute treatment

Acute treatments can be classified as first-line, second-line, third-line and adjunct (Table 3), and should be used in a stepped care approach32 (Fig. 2). Our recommendations for each line of treatment are outlined below. The medications at each stage were selected on the basis of efficacy, tolerability, safety, cost and availability.

Preventive therapy, in addition, may be indicated at any stage. In general, initiation of preventive therapy is indicated in patients who are adversely affected on ≥2 days per month despite acute treatment optimized according to the stepped care approach. NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

First-line medication

Over-the-counter analgesics are used worldwide for acute migraine treatment44. Those with proven efficacy include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and the strongest evidence supports use of acetylsalicylic acid, ibuprofen and diclofenac potassium as first-line medications45,46,47. Paracetamol has less efficacy48 and should be used only in those who are intolerant of NSAIDs.

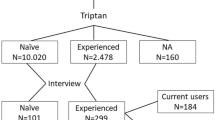

Second-line medication

Patients for whom over-the-counter analgesics provide inadequate headache relief should be offered a triptan. All triptans have well-documented effectiveness, but availability of and access to each vary between countries. Triptans are most effective when taken early in an attack, when the headache is still mild49,50. However, no evidence supports the use of triptans during the aura phase of a migraine attack. If one triptan is ineffective, others might still provide relief51,52. When all other triptans have failed or in patients who rapidly reach peak headache intensity or cannot take oral triptans because of vomiting, sumatriptan by subcutaneous injection can be useful53.

Some patients can experience relapses, which are defined as a return of symptoms within 48 h after apparently successful treatment. Upon relapse, patients can repeat their triptan treatment or combine the triptan with simultaneous intake of fast-acting formulations of naproxen sodium, ibuprofen lysine or diclofenac potassium54,55. However, patients should be informed that repeating the treatment does not preclude further relapses and ultimately increases the risk of developing MOH.

Third-line medication

If all available triptans fail after an adequate trial period (no or insufficient therapeutic response in at least three consecutive attacks) or their use is contraindicated, alternatives are currently limited. Ditans or gepants could be used, but their availability is currently very limited. Lasmiditan is the only ditan approved for acute treatment of migraine, and ubrogepant and rimegepant are the only gepants approved. Indirect comparison of data from randomized controlled trials suggests that the efficacy of lasmiditan is comparable to that of triptans56,57,58, but its use is associated with temporary driving impairment, which is likely to discourage widespread use. Individuals who take lasmiditan might be unable to self-assess their driving competence and should not operate machinery for at least 8 h after intake.

Adjunct medication

For patients who experience nausea and/or vomiting during migraine attacks, prokinetic antiemetics such as domperidone and metoclopramide are useful oral adjuncts.

Medications to avoid

Oral ergot alkaloids are poorly effective and potentially toxic, and should not be used as a substitute for triptans59. The efficacy of opioids and barbiturates is questionable, and both are associated with considerable adverse effects and the risk of dependency60. All of these medications should, therefore, be avoided for the acute treatment of migraine.

Recommendations

-

Offer acute medication to everyone who experiences migraine attacks.

-

Advise use of acute medications early in the headache phase of the attack, as effectiveness depends on timely use with the correct dose.

-

Advise patients that frequent, repeated use of acute medication risks development of MOH.

-

Use NSAIDs (acetylsalicylic acid, ibuprofen or diclofenac potassium) as first-line medication.

-

Use triptans as second-line medication.

-

Consider combining triptans with fast-acting NSAIDs to avert recurrent relapse.

-

Consider ditans and gepants as third-line medications.

-

Use prokinetic antiemetics (domperidone or metoclopramide) as adjunct oral medications for nausea and/or vomiting.

-

Avoid oral ergot alkaloids, opioids and barbiturates.

Step 5: Preventive treatment

Initiation and termination

In patients whose migraine continues to impair their quality of life despite optimized acute therapy, additional preventive therapy should be considered (Table 4). In practice, patients who are considered for preventive treatment remain adversely affected on at least 2 days per month32, although this should not be regarded as an absolute rule32. Aside from migraine frequency, clinicians should always consider factors such as the severity of attacks, the duration of attacks (for example, menstruation-related attacks tend to last longer) and migraine-related disability. A further indication for preventive therapy is overuse of acute medication.

Efficacy of preventive therapy is rarely observed immediately. Only after several weeks or months can efficacy be ascertained, so patients should be discouraged from abandoning the treatment in these early stages on the grounds of apparent inefficacy32. If a therapeutic dose of an oral preventive medication is ineffective after 2–3 months, an alternative should be tried32,61,62. For monoclonal antibody treatments that target calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) or its receptor, efficacy should be assessed only after 3–6 months. For onabotulinumtoxinA, efficacy should be assessed after 6–9 months.

Failure of one preventive treatment does not predict failure of treatment with other drug classes, except when failure is due to poor adherence. Treatment adherence is often very poor but can be improved by simplified dosing schedules (once daily or less)32. For most preventive medications, clinical experience suggests that pausing can be considered when treatment has been successful for 6–12 months32. The purpose of pausing is to ascertain whether preventive treatment can be stopped, which minimizes the risk of unnecessary drug exposure and allows some patients to manage their migraine with acute medications only. A useful measure to quantify the degree of preventive treatment success is to calculate the percentage reduction in monthly migraine days or monthly headache days of moderate-to-severe intensity. However, a pragmatic approach is needed and clinicians should decide to pause preventive therapy on a case-by-case basis.

Current standard of care

As for acute medications, preventive treatments can be classified as first-line, second-line and third-line options (Table 4). However, choice of medication and the order of use depend on local practice guidelines and local availability, costs and reimbursement policies.

First-line medications are beta blockers without intrinsic sympathomimetic activity (atenolol, bisoprolol, metoprolol or propranolol)63, topiramate64 and candesartan65,66. If these fail, second-line medications include flunarizine67, amitriptyline68 and sodium valproate69, although valproate is strictly contraindicated in women of childbearing potential, which greatly limits its utility in migraine70,71,72. Third-line medications are the four CGRP monoclonal antibodies erenumab, fremanezumab, galcanezumab and eptinezumab. These antibodies have been approved for the preventive treatment of migraine in the past few years61. In Europe, regulatory restrictions limit their use to patients in whom other preventive drugs have failed or are contraindicated61.

Non-pharmacological therapies

A range of non-pharmacological preventive therapies can be used either as adjuncts to acute and preventive medications or instead of them if medication use is contraindicated. Some evidence supports the use of non-invasive neuromodulatory devices73, biobehavioural therapy74 and acupuncture75, although a study of acupuncture indicated that it is not superior to sham acupuncture76. Contrary to popular belief, little to no evidence exists for physical therapy77, spinal manipulation and dietary approaches78. We make no recommendations about other therapeutic options, such as melatonin, magnesium and riboflavin, as limited evidence for their efficacy is available and their use in clinical practice is limited.

Recommendations

-

Consider preventive treatment in patients who are adversely affected by migraine on ≥2 days per month despite optimized acute treatment.

-

Use beta blockers (atenolol, bisoprolol, metoprolol or propranolol), topiramate or candesartan as first-line medications.

-

Use flunarizine, amitriptyline or (in men) sodium valproate as second-line medications.

-

Consider CGRP monoclonal antibodies as third-line medications.

-

Consider neuromodulatory devices, biobehavioural therapy and acupuncture as adjuncts to acute and preventive medication or as stand-alone preventive treatment when medication is contraindicated.

Step 6: Managing migraine in special populations

Older people

Migraine often remits with older age whereas the incidence of many secondary headaches increases79,80,81. Onset of apparent migraine after the age of 50 years should, therefore, arouse suspicion of an underlying cause. In individuals whose migraine persists from earlier life into later years, clinical management often remains unchanged in practice. Little formal evidence is available with respect to therapeutic approaches in older people with migraine.

Nonetheless, known and possible unknown comorbidities need to be considered, as well as harm that might be caused by drug-specific adverse effects82, to which older people are generally more susceptible. For instance, use of triptans in older people is often advised against owing to the relatively high likelihood that these patients have cardiovascular disease and/or cardiovascular risk factors. However, no robust evidence supports an increased risk of cerebrovascular or cardiovascular events in older people owing to triptan use per se83. Nonetheless, clinicians are advised to regularly monitor blood pressure in older patients with migraine who use triptans, in addition to periodical assessment of cardiovascular risk factors84.

Children and adolescents

Migraine is common among children and its prevalence increases in adolescence85. As in adults, diagnosis is primarily based on the medical history, although the criteria are slightly different — the duration of migraine attacks can be 2 to 72 h4. The clinical features of migraine in children and adolescents also differ somewhat from those in adults — the attacks are often shorter4, the headache is more often bilateral and less often pulsating, and gastrointestinal disturbances are commonly prominent32. Descriptions of these features might be more reliably provided by parents than children, and parents will also provide a better account of lifestyle factors that might need to be addressed86.

In children and young adolescents, clinical management usually requires active help from family members and teachers86, so education of both is necessary. Bed-rest alone might suffice in children with attacks that have a short duration. When needed, ibuprofen is recommended as first-line medication, at a dose appropriate for body weight32. Domperidone can be used for nausea in adolescents aged 12–17 years87, although oral administration is unlikely to prevent vomiting.

The evidence base for medication therapy in children and adolescents is confounded by a high placebo response in clinical trials88,89. As a consequence, the apparent therapeutic gain is low, and this effect probably explains why a benefit of triptans has not been demonstrated in children. For adolescents aged 12–17 years, multiple NSAIDs and triptans have been approved for acute treatment of migraine90,91, and some evidence indicates that nasal spray formulations of sumatriptan and zolmitriptan are the most effective92. If acute medication provides insufficient pain relief, referral to specialist care is indicated32. In practice, propranolol, amitriptyline and topiramate are used for preventive treatment, although their effectiveness in children and adolescents has not been proven in clinical trials88,89.

Pregnant and breastfeeding women

Migraine often remits during pregnancy, but if treatment is continued, the potential for harm to the fetus demands special consideration93. Despite relatively poor efficacy, paracetamol should be used as the first-line medication for acute treatment of migraine in pregnancy48; NSAIDs can be used only during the second trimester93,94. Triptans should be used only under the strict supervision of a specialist, as the safety data available are limited and originate from post-marketing surveillance; most data relate to the use of sumatriptan32. For nausea associated with migraine in pregnancy, metoclopramide can be used94,95.

Preventive migraine medications are best avoided during pregnancy owing to the potential for fetal harm. However, if preventive therapy is considered clinically indicated because of frequent and disabling migraine attacks, the best available safety data support the use of propranolol or, if propranolol is contraindicated, amitriptyline. Both should be used under specialist supervision to adequately monitor any potential fetal harm32. Topiramate, candesartan and sodium valproate are contraindicated; sodium valproate is known to be teratogenic, so must not be used70,94, and the use of topiramate and candesartan is associated with adverse effects on the fetus.

Migraine medication therapy in the post-partum period also requires caution because of potential risks to the infant. Paracetamol is the preferred acute medication, although ibuprofen and sumatriptan are also considered safe94. If preventive medication is required, propranolol is the recommended first choice as it has the best safety profile94. Pharmacological treatments for migraine during pregnancy and breastfeeding have been reviewed in more detail elsewhere94.

Women with menstrual migraine

Approximately 8% of women with migraine experience migraine attacks that are exclusively related to their menstruation, referred to as pure menstrual migraine96,97. If optimized acute medication therapy does not suffice for these patients, initiation of perimenstrual preventive treatment should be considered. This approach typically involves daily intake of a long-acting NSAID (for example, naproxen) or triptan (for example, frovatriptan or naratriptan) for 5 days, beginning 2 days before the expected first day of menstruation98,99,100,101. Some women with pure menstrual migraine without aura benefit from continuous use (that is, without a break) of combined hormonal contraceptives. By contrast, combined hormonal contraceptives are contraindicated in women with migraine with aura regardless of any association with their menstrual cycle, owing to an associated increase in the risk of stroke32.

Recommendations

-

In patients with apparent late-onset migraine, suspect an underlying cause.

-

In older people, consider the higher risks of secondary headache, comorbidities and adverse events with older age.

-

In children and adolescents with migraine, bed rest alone might suffice; if not, use ibuprofen for acute treatment and propranolol, amitriptyline or topiramate for prevention.

-

In pregnant or breastfeeding women, use paracetamol for acute treatment and avoid preventive medication whenever possible.

-

In women with menstrual migraine, consider perimenstrual preventive therapy with a long-acting NSAID or triptan.

Step 7: Follow-up, treatment response and failure

Active follow-up is the only appropriate means of determining outcome and provides the opportunity to review both diagnosis and treatment strategies. The response to treatment should be evaluated within 2–3 months after initiation or a change in treatment, and regularly thereafter, though not necessarily at short intervals (for example, 6–12 months). Evaluation of treatment responses should include a review of effectiveness, adverse events and adherence.

Key outcome measures for effectiveness are attack frequency, attack severity and migraine-related disability32. Attack frequency is usually measured in headache or migraine days per month. Severity is usually expressed as pain intensity rather than functional consequence, which should be separately assessed. Headache calendars are extremely useful for capturing these measures and require little time commitment if completed only on symptomatic days32. In addition, headache calendars are valuable for monitoring acute medication use. At follow-up assessments, the self-administered Migraine Treatment Optimization Questionnaire (mTOQ-4) can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of acute medications102, whereas the self-completed eight-item HURT questionnaire (Headache Under-Response to Treatment) can be used to assess the effectiveness of an intervention and generates suggestions for changes to improve effectiveness103 (Box 3).

When treatment fails

A conclusion that treatment has failed should be made with caution and must always be preceded by a thorough review of the underlying reasons. In some cases, apparent failures might be remediable, such as when failure is due to poor adherence or suboptimal dosing32. Whereas some patients benefit from higher doses, others might benefit from lower doses that have fewer adverse effects and therefore improve adherence. Alternatives when first-line medications fail are outlined above (see Step 4 and Step 5). If all treatments fail, the diagnosis should be questioned and specialist referral is indicated32.

When specialist referral is needed

Approximately 90% of people who seek professional care for migraine should be treated in primary care104. Referral to specialist care should be reserved for the minority of patients whose condition is diagnostically challenging, difficult to treat or complicated by comorbidities32. Specialist care provides access to greater expertise maintained by experience and to multidisciplinary care. However, specialist capacity is limited and the cost is much higher105.

Recommendations

-

Evaluate treatment responses shortly after initiation (after 2–3 months) or a change of treatment and regularly thereafter (every 6–12 months).

-

Evaluate the effectiveness of treatment by assessing attack frequency, attack severity and migraine-related disability.

-

When outcomes are suboptimal, review the diagnosis, treatment strategy, dosing and adherence.

-

If all treatment fails, question the diagnosis and consider specialist referral.

Step 8: Managing complications

Medication overuse headache

MOH is a chronic headache disorder characterized by headache on ≥15 days per month. It develops over a variable period of time in patients with a pre-existing headache disorder as a result of regular overuse of acute or symptomatic headache medication4. Patients with migraine account for approximately two thirds of all cases of MOH, although this estimate is based on limited evidence and might be too low106.

Withdrawal of the overused medication is the necessary and only remedy for MOH107. Expert consensus is that abrupt withdrawal is preferable to slow withdrawal, except for opioids30. This process can be managed in primary care unless addictive drugs, such as opioids, are involved108,109. Patient education is a key component of the clinical management of MOH, as withdrawal is usually followed by worsening before recovery30,110. Preventive therapy (pharmacological and/or non-pharmacological) appropriate to the antecedent headache can be started in parallel with acute medication withdrawal or upon re-emergence of the headache disorder30, although this topic remains a subject of debate111,112.

Transformation to chronic migraine

Some estimates suggest that up to 3% of patients with episodic migraine experience transformation to chronic migraine each year113. The reliability of such estimates is uncertain because chronic migraine is often conflated with MOH114, but transformation to chronic migraine does occur. Recognized risk factors include female sex, a high headache frequency, inadequate treatment, overuse of acute medications and a range of comorbidities, including depression, anxiety and obesity115,116,117,118. Recognition of these risk factors is part of good clinical management, as their modification can prevent transformation.

Once chronic migraine has developed, its management is challenging and referral to specialist care is usually necessary32. If MOH, which frequently causes symptoms that suggest chronic migraine, can be ruled out, then a preventive treatment should be established114. Individuals with chronic migraine should also be educated on the modifiable risk factors for chronic migraine so that they can make lifestyle changes that might help.

Preventive medications for which evidence supports effectiveness in chronic migraine include topiramate119, onabotulinumtoxinA120 and CGRP monoclonal antibodies121. Topiramate is the drug of first choice owing to its much lower cost. Regulatory restrictions generally limit the use of onabotulinumtoxinA and CGRP antibodies to patients in whom two or three other preventive medications have failed, despite the fact that topiramate is the only other treatment with evidence supporting its use. Three CGRP antibodies (erenumab, fremanezumab and galcanezumab) have been proven to be beneficial for patients in whom at least two other preventive medications have failed122,123,124. As in episodic migraine, the choice of preventive medication and their order of use depends on local practice guidelines, availability, cost and reimbursement policies. No robust data from random controlled trials support the use of beta blockers, candesartan or amitriptyline for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine, although they are commonly used in clinical practice.

Recommendations

-

Educate patients with migraine about the risk of MOH with frequent overuse of acute medication.

-

Manage established MOH by explanation and withdrawal of the overused medication; abrupt withdrawal is preferred, except for opioids.

-

Recognize and, when possible, modify risk factors for the transformation of episodic migraine to chronic migraine.

-

Refer patients with chronic migraine to specialist care.

-

Once MOH is ruled out, initiate preventive medication therapy for chronic migraine; evidence-based treatment options are topiramate, onabotulinumtoxinA and CGRP monoclonal antibodies.

Step 9: Recognizing and managing comorbidities

Migraine is associated with anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances and chronic pain conditions (for example, neck and lower back pain)125,126,127,128,129. These associations are more pronounced in people with chronic migraine than in those with episodic migraine130. Obesity is also an important risk factor for transformation from episodic migraine to chronic migraine and should be accounted for in the clinical evaluation131. Furthermore, migraine with aura has been associated with cardiovascular events in women132.

Recognition of comorbid conditions in migraine is important because they can influence drug choice. For example, topiramate is the preferred treatment for patients with obesity owing to its association with weight loss. For patients with depression or sleep disturbances, amitriptyline is most likely to be of benefit. Recognition of comorbidities is also important because their alleviation can improve treatment outcomes for migraine, and vice versa.

Recommendations

-

Ensure that comorbidities are identified in patients with migraine, as they can affect treatment choice and outcomes.

-

Adjust treatments accordingly and consider possible interactions between drug-related adverse effects and the patient’s comorbidity profile.

Step 10: Long-term follow-up

Long-term management of migraine should be the responsibility of primary care. Referral from specialist care back to primary care should be timely, coordinated with the general practitioner and accompanied by a comprehensive treatment plan that includes recommendations for re-evaluation and steps to be taken for each of the likely outcomes. In general, timely return to primary care can be made once the patient experiences sustained efficacy with preventive therapy for up to 6 months with no substantial treatment-related adverse effects.

In primary care, the main goal of follow-up is to maintain stability of adequate outcomes, whether achieved in primary or specialist care, and to react appropriately to any change that might call for review. Neither purpose requires regular routine contact, which should, therefore, be avoided unless necessary in the context of repeat prescriptions. Instead, primary care physicians should emphasize patient education and self-efficacy with respect to judging when a return visit is necessary.

Recommendations

-

Primary care should be responsible for the long-term management of patients with migraine, maintaining stability and reacting to change.

-

Referral from specialist back to primary care should be timely and accompanied by a comprehensive treatment plan.

-

The patient can be referred back to primary care once sustained efficacy with preventive therapy for up to 6 months is obtained with no substantial treatment-related adverse effects.

Conclusions

Migraine is a ubiquitous neurological disorder that adds substantially to the global burden of disease. Despite the existence of comprehensive diagnostic criteria and a multitude of therapeutic options, diagnosis and clinical management of migraine remain suboptimal worldwide. This Consensus Statement was developed by experts from Europe to provide generally applicable recommendations for the diagnosis and management of migraine and to promote best clinical practices. The recommendations are based on published evidence and expert opinion, and will be updated when new information and treatments emerge.

References

Ashina, M. Migraine. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 1866–1876 (2020).

GBD 2016 Neurology Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 18, 459–480 (2019).

GBD 2016 Headache Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 17, 954–976 (2018).

[No authors listed] Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 38, 1–211 (2018).

Rasmussen, B. K. & Olesen, J. Migraine with aura and migraine without aura: an epidemiological study. Cephalalgia 12, 221–228 (1992).

Hansen, J. M. et al. Migraine headache is present in the aura phase. Neurology 79, 2044–2049 (2012).

Natoli, J. L. et al. Global prevalence of chronic migraine: a systematic review. Cephalalgia 30, 599–609 (2010).

Ashina, M. et al. Migraine and the trigeminovascular system–40 years and counting. Lancet Neurol. 18, 795–804 (2019).

Ashina, M. et al. Migraine: disease characterisation, biomarkers, and precision medicine. Lancet 397, 1496–1504 (2021).

Ashina, M. et al. Migraine: integrated approaches to clinical management and emerging treatments. Lancet 397, 1505–1518 (2021).

Katsarava, Z., Mania, M., Lampl, C., Herberhold, J. & Steiner, T. J. Poor medical care for people with migraine in Europe – evidence from the Eurolight study. J. Headache Pain 19, 10 (2018).

Ashina, M. et al. Migraine: epidemiology and systems of care. Lancet 397, 1485–1495 (2021).

Rasmussen, B. K., Jensen, R., Schroll, M. & Olesen, J. Epidemiology of headache in a general population–a prevalence study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 44, 1147–1157 (1991).

Karsan, N. & Goadsby, P. J. Biological insights from the premonitory symptoms of migraine. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 14, 699–710 (2018).

Giffin, N. J., Lipton, R. B., Silberstein, S. D., Olesen, J. & Goadsby, P. J. The migraine postdrome. Neurology 87, 309–313 (2016).

Russell, M. B. & Olesen, J. A nosographic analysis of the migraine aura in a general population. Brain 119, 355–361 (1996).

Serrano, D. et al. Fluctuations in episodic and chronic migraine status over the course of 1 year: implications for diagnosis, treatment and clinical trial design. J. Headache Pain 18, 101 (2017).

Russell, M. B., Hilden, J., Sørensen, S. A. & Olesen, J. Familial occurrence of migraine without aura and migraine with aura. Neurology 43, 1369–1373 (1993).

Ulrich, V., Gervil, M., Kyvik, K. O., Olesen, J. & Russell, M. B. Evidence of a genetic factor in migraine with aura: a population-based Danish twin study. Ann. Neurol. 45, 242–246 (1999).

Russell, M. B., Fenger, K. & Olesen, J. The family history of migraine. Direct versus indirect information. Cephalalgia 16, 156–160 (1996).

Phillip, D., Lyngberg, A. & Jensen, R. Assessment of headache diagnosis. A comparative population study of a clinical interview with a diagnostic headache diary. Cephalalgia 27, 1–8 (2007).

Lipton, R. B. et al. A self-administered screener for migraine in primary care: the ID Migraine validation study. Neurology 61, 375–382 (2003).

Láinez, M. J. A. et al. Development and validation of the migraine screen questionnaire (MS-Q). Headache 45, 1328–1338 (2005).

Brighina, F. et al. A validation study of an Italian version of the ID Migraine: preliminary results. J. Headache Pain 6, 216–219 (2005).

Gil-Gouveia, R. & Martins, I. Validation of the Portuguese version of ID-Migraine. Headache 50, 396–402 (2010).

Csépány, É. et al. The validation of the Hungarian version of the ID-migraine questionnaire. J. Headache Pain 19, 106 (2018).

Delic, D. et al. Translation and transcultural validation of migraine screening questionnaire (MS-Q). Med. Arch. 72, 430–433 (2018).

Ashina, S. et al. Tension-type headache. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 7, 24 (2021).

Fischera, M., Marziniak, M., Gralow, I. & Evers, S. The incidence and prevalence of cluster headache: a meta-analysis of population-based studies. Cephalalgia 28, 614–618 (2008).

Diener, H.-C. et al. Pathophysiology, prevention, and treatment of medication overuse headache. Lancet Neurol. 18, 891–902 (2019).

Do, T. P. et al. Red and orange flags for secondary headaches in clinical practice. Neurology 92, 134–144 (2019).

Steiner, T. J. et al. Aids to management of headache disorders in primary care (2nd edition). J. Headache Pain 20, 57 (2019).

Mitsikostas, D. D. et al. European Headache Federation consensus on technical investigation for primary headache disorders. J. Headache Pain 17, 5 (2015).

Brenner, D. J. & Hall, E. J. Computed tomography–an increasing source of radiation exposure. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 2277–2284 (2007).

Evans, R. W. et al. Neuroimaging for migraine: the American Headache Society systematic review and evidence-based guideline. Headache 60, 318–336 (2019).

Sandrini, G. et al. Neurophysiological tests and neuroimaging procedures in non-acute headache (2nd edition). Eur. J. Neurol. 18, 373–381 (2011).

Callaghan, B. C., Kerber, K. A., Pace, R. J., Skolarus, L. E. & Burke, J. F. Headaches and neuroimaging: high utilization and costs despite guidelines. JAMA Intern. Med. 174, 819–821 (2014).

Evans, R. W. Incidental findings and normal anatomical variants on MRI of the brain in adults for primary headaches. Headache 57, 780–791 (2017).

Lipton, R. B. et al. Unmet acute treatment needs from the 2017 Migraine in America Symptoms and Treatment Study. Headache 59, 1310–1323 (2019).

Munksgaard, S. B. et al. What do the patients with medication overuse headache expect from treatment and what are the preferred sources of information? J. Headache Pain 12, 91–96 (2011).

Hepp, Z. et al. Adherence to oral migraine-preventive medications among patients with chronic migraine. Cephalalgia 35, 478–488 (2015).

Lipton, R. B., Pavlovic, J. M., Haut, S. R., Grosberg, B. M. & Buse, D. C. Methodological issues in studying trigger factors and premonitory features of migraine. Headache 54, 1661–1669 (2014).

Marmura, M. J. Triggers, protectors, and predictors in episodic migraine. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 22, 81 (2018).

World Health Organization. Atlas of headache disorders and resources in the world 2011 (WHO, 2011).

Kirthi, V., Derry, S. & Moore, R. A. Aspirin with or without an antiemetic for acute migraine headaches in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 4, CD008041 (2013).

Rabbie, R., Derry, S. & Moore, R. A. Ibuprofen with or without an antiemetic for acute migraine headaches in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 4, CD008039 (2013).

Derry, S., Rabbie, R. & Moore, R. A. Diclofenac with or without an antiemetic for acute migraine headaches in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2, CD008783 (2012).

Derry, S. & Moore, R. A. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) with or without an antiemetic for acute migraine headaches in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 4, CD008040 (2013).

Goadsby, P. J. et al. Early vs. non-early intervention in acute migraine – ‘Act when Mild (AwM)’. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of almotriptan. Cephalalgia 28, 383–391 (2008).

Lantéri-Minet, M., Mick, G. & Allaf, B. Early dosing and efficacy of triptans in acute migraine treatment: the TEMPO study. Cephalalgia 32, 226–235 (2012).

Färkkilä, M. et al. Eletriptan for the treatment of migraine in patients with previous poor response or tolerance to oral sumatriptan. Cephalalgia 23, 463–471 (2003).

Dahlöf, C. G. H. Infrequent or non-response to oral sumatriptan does not predict response to other triptans–review of four trials. Cephalalgia 26, 98–106 (2006).

Derry, C. J., Derry, S. & Moore, R. A. Sumatriptan (all routes of administration) for acute migraine attacks in adults – overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014 5, CD009108 (2014).

Law, S., Derry, S. & Moore, R. A. Sumatriptan plus naproxen for the treatment of acute migraine attacks in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 4, CD008541 (2016).

[No authors listed] Treatment of migraine attacks with sumatriptan. The Subcutaneous Sumatriptan International Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 325, 316–321 (1991).

Lipton, R. B. et al. Rimegepant, an oral calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist, for migraine. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 142–149 (2019).

Lipton, R. B. et al. Effect of ubrogepant vs placebo on pain and the most bothersome associated symptom in the acute treatment of migraine: the ACHIEVE II randomized clinical trial. JAMA 322, 1887–1898 (2019).

Goadsby, P. J. et al. Phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of lasmiditan for acute treatment of migraine. Brain 142, 1894–1904 (2019).

Tfelt-Hansen, P. C. & Koehler, P. J. History of the use of ergotamine and dihydroergotamine in migraine from 1906 and onward. Cephalalgia 28, 877–886 (2008).

Bigal, M. E. & Lipton, R. B. Excessive opioid use and the development of chronic migraine. Pain 142, 179–182 (2009).

Sacco, S. et al. European Headache Federation guideline on the use of monoclonal antibodies acting on the calcitonin gene related peptide or its receptor for migraine prevention. J. Headache Pain 20, 6 (2019).

Bendtsen, L. et al. Guideline on the use of onabotulinumtoxinA in chronic migraine: a consensus statement from the European Headache Federation. J. Headache Pain 19, 91 (2018).

Jackson, J. L. et al. Beta-blockers for the prevention of headache in adults, a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 14, e0212785 (2019).

Linde, M., Mulleners, W. M., Chronicle, E. P. & McCrory, D. C. Topiramate for the prophylaxis of episodic migraine in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 6, CD010610 (2013).

Tronvik, E., Stovner, L. J., Helde, G., Sand, T. & Bovim, G. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with an angiotensin II receptor blocker: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 289, 65–69 (2003).

Stovner, L. J. et al. A comparative study of candesartan versus propranolol for migraine prophylaxis: A randomised, triple-blind, placebo-controlled, double cross-over study. Cephalalgia 34, 523–532 (2014).

Stubberud, A., Flaaen, N. M., McCrory, D. C., Pedersen, S. A. & Linde, M. Flunarizine as prophylaxis for episodic migraine: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Pain 160, 762–772 (2019).

Jackson, J. L. et al. Tricyclic antidepressants and headaches: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 341, C5222 (2010).

Linde, M., Mulleners, W. M., Chronicle, E. P. & McCrory, D. C. Valproate (valproic acid or sodium valproate or a combination of the two) for the prophylaxis of episodic migraine in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 6, CD010611 (2013).

Vatzaki, E. et al. Latest clinical recommendations on valproate use for migraine prophylaxis in women of childbearing age: overview from European Medicines Agency and European Headache Federation. J. Headache Pain 19, 68 (2018).

Dodick, D. W. et al. Topiramate versus amitriptyline in migraine prevention: a 26-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, parallel-group noninferiority trial in adult migraineurs. Clin. Ther. 31, 542–559 (2009).

Couch, J. R. Amitriptyline in the prophylactic treatment of migraine and chronic daily headache. Headache 51, 33–51 (2011).

Reuter, U., McClure, C., Liebler, E. & Pozo-Rosich, P. Non-invasive neuromodulation for migraine and cluster headache: a systematic review of clinical trials. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 90, 796–804 (2019).

Sullivan, A., Cousins, S. & Ridsdale, L. Psychological interventions for migraine: a systematic review. J. Neurol. 263, 2369–2377 (2016).

Linde, K. et al. Acupuncture for the prevention of episodic migraine. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, CD001218 (2016).

Diener, H.-C. et al. Efficacy of acupuncture for the prophylaxis of migraine: a multicentre randomised controlled clinical trial. Lancet 5, 310–316 (2006).

Luedtke, K., Allers, A., Schulte, L. H. & May, A. Efficacy of interventions used by physiotherapists for patients with headache and migraine-systematic review and meta-analysis. Cephalalgia 36, 474–492 (2016).

Hindiyeh, N. A. et al. The role of diet and nutrition in migraine triggers and treatment: a systematic literature review. Headache 60, 1300–1316 (2020).

Bigal, M. E. & Lipton, R. B. Migraine at all ages. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 10, 207–213 (2006).

Bigal, M. E., Liberman, J. N. & Lipton, R. B. Age-dependent prevalence and clinical features of migraine. Neurology 67, 246–251 (2006).

Bamford, C. C., Mays, M. & Tepper, S. J. Unusual headaches in the elderly. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 15, 295–301 (2011).

Vongvaivanich, K., Lertakyamanee, P., Silberstein, S. D. & Dodick, D. W. Late-life migraine accompaniments: a narrative review. Cephalalgia 35, 894–911 (2015).

Diener, H.-C. The risks or lack thereof of migraine treatments in vascular disease. Headache 60, 649–653 (2020).

World Health Organization. Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Guidelines for assessment and management of cardiovascular risk (WHO, 2007).

Barnes, N. P. Migraine headache in children. BMJ Clin. Evid. 2015, 0318 (2015).

Hershey, A. D. Current approaches to the diagnosis and management of paediatric migraine. Lancet Neurol. 9, 190–204 (2010).

Oskoui, M. et al. Practice guideline update summary: acute treatment of migraine in children and adolescents: report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology 93, 487–499 (2019).

Oskoui, M. et al. Practice guideline update summary: pharmacologic treatment for pediatric migraine prevention: report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology 93, 500–509 (2019).

Evers, S., Marziniak, M., Frese, A. & Gralow, I. Placebo efficacy in childhood and adolescence migraine: an analysis of double-blind and placebo-controlled studies. Cephalalgia 29, 436–444 (2009).

Faber, A. J., Lagman-Bartolome, A. M. & Rajapakse, T. Drugs for the acute treatment of migraine in children and adolescents. Paediatr. Child Health 22, 454–458 (2017).

Orr, S. L. et al. Paediatric migraine: evidence-based management and future directions. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 14, 515–527 (2018).

Richer, L. et al. Drugs for the acute treatment of migraine in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 4, CD005220 (2016).

Goadsby, P. J., Goldberg, J. & Silberstein, S. D. Migraine in pregnancy. BMJ 336, 1502–1504 (2008).

Amundsen, S., Nordeng, H., Nezvalová-Henriksen, K., Stovner, L. J. & Spigset, O. Pharmacological treatment of migraine during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 11, 209–219 (2015).

Pasternak, B., Svanström, H., Mølgaard-Nielsen, D., Melbye, M. & Hviid, A. Metoclopramide in pregnancy and risk of major congenital malformations and fetal death. JAMA 310, 1601–1611 (2013).

Vetvik, K. G. & Russell, M. B. Are menstrual and nonmenstrual migraine attacks different? Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 15, 339–342 (2011).

Vetvik, K. G., Macgregor, E. A., Lundqvist, C. & Russell, M. B. Prevalence of menstrual migraine: a population-based study. Cephalalgia 34, 280–288 (2014).

Newman, L. et al. Naratriptan as short-term prophylaxis of menstrually associated migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Headache 41, 248–256 (2001).

Silberstein, S. & Patel, S. Menstrual migraine: an updated review on hormonal causes, prophylaxis and treatment. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 15, 2063–2070 (2014).

van Dijkman, S. C., de Jager, N. C. B., Rauwé, W. M., Danhof, M. & Della Pasqua, O. Effect of age-related factors on the pharmacokinetics of lamotrigine and potential implications for maintenance dose optimisation in future clinical trials. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 57, 1039–1053 (2018).

Silberstein, S. D. et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults. Neurology 78, 1337–1345 (2012).

Lipton, R. B. et al. Validity and reliability of the migraine-treatment optimization questionnaire. Cephalalgia 29, 751–759 (2009).

Steiner, T. J. et al. The headache under-response to treatment (HURT) questionnaire, an outcome measure to guide follow-up in primary care: development, psychometric evaluation and assessment of utility. J. Headache Pain 19, 15 (2018).

Steiner, T. J. et al. Recommendations for headache service organisation and delivery in Europe. J. Headache Pain 12, 419–426 (2011).

World Health Organization. Building the economic case for primary health care: a scoping review. Technical series on primary health care (WHO, 2018).

GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 390, 1211–1259 (2017).

Diener, H. C. et al. European Academy of Neurology guideline on the management of medication-overuse headache. Eur. J. Neurol. 27, 1102–1116 (2020).

Kristoffersen, E. S. et al. Brief intervention for medication-overuse headache in primary care. The BIMOH study: a double-blind pragmatic cluster randomised parallel controlled trial. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 86, 505–512 (2015).

Kristoffersen, E. S. et al. Brief intervention by general practitioners for medication-overuse headache, follow-up after 6 months: a pragmatic cluster-randomised controlled trial. J. Neurol. 263, 344–353 (2016).

Lai, J. T. F. et al. Should we educate about the risks of medication overuse headache? J. Headache Pain 15, 10 (2014).

Pijpers, J. A. et al. Acute withdrawal and botulinum toxin A in chronic migraine with medication overuse: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Brain 142, 1203–1214 (2019).

Carlsen, L. N. et al. Comparison of 3 treatment strategies for medication overuse headache: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 77, 1069–1078 (2020).

Buse, D. C. et al. Chronic migraine prevalence, disability, and sociodemographic factors: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study. Headache 52, 1456–1470 (2012).

Diener, H.-C. et al. Chronic migraine — classification, characteristics and treatment. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 8, 162–171 (2012).

Buse, D. C., Greisman, J. D., Baigi, K. & Lipton, R. B. Migraine progression: a systematic review. Headache 59, 306–338 (2019).

Probyn, K. et al. Prognostic factors for chronic headache: a systematic review. Neurology 89, 291–301 (2017).

Xu, J., Kong, F. & Buse, D. C. Predictors of episodic migraine transformation to chronic migraine: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational cohort studies. Cephalalgia 40, 503–516 (2019).

Lipton, R. B. et al. Ineffective acute treatment of episodic migraine is associated with new-onset chronic migraine. Neurology 84, 688–695 (2015).

Silberstein, S. et al. Topiramate treatment of chronic migraine: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of quality of life and other efficacy measures. Headache 49, 1153–1162 (2009).

Herd, C. P. et al. Botulinum toxins for the prevention of migraine in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 6, CD011616 (2018).

Charles, A. & Pozo-Rosich, P. Targeting calcitonin gene-related peptide: a new era in migraine therapy. Lancet 394, 1765–1774 (2019).

Reuter, U. et al. Efficacy and tolerability of erenumab in patients with episodic migraine in whom two-to-four previous preventive treatments were unsuccessful: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b study. Lancet 392, 2280–2287 (2018).

Ferrari, M. D. et al. Fremanezumab versus placebo for migraine prevention in patients with documented failure to up to four migraine preventive medication classes (FOCUS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet 394, 1030–1040 (2019).

Ruff, D. D. et al. Efficacy of galcanezumab in patients with episodic migraine and a history of preventive treatment failure: results from two global randomized clinical trials. Eur. J. Neurol. 27, 609–618 (2020).

Dresler, T. et al. Understanding the nature of psychiatric comorbidity in migraine: a systematic review focused on interactions and treatment implications. J. Headache Pain 20, 51 (2019).

Lampl, C. et al. Headache, depression and anxiety: associations in the Eurolight project. J. Headache Pain 17, 59 (2016).

Buse, D. C. et al. Sleep disorders among people with migraine: results from the chronic migraine epidemiology and outcomes (CaMEO) study. Headache 59, 32–45 (2019).

Ashina, S. et al. Increased pain sensitivity in migraine and tension-type headache coexistent with low back pain: A cross-sectional population study. Eur. J. Pain 22, 904–914 (2018).

Ashina, S. et al. Prevalence of neck pain in migraine and tension-type headache: a population study. Cephalalgia 35, 211–219 (2015).

Buse, D. C., Manack, A., Serrano, D., Turkel, C. & Lipton, R. B. Sociodemographic and comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine and episodic migraine sufferers. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 81, 428–432 (2010).

Bigal, M. E. & Lipton, R. B. Obesity is a risk factor for transformed migraine but not chronic tension-type headache. Neurology 67, 252–257 (2006).

Kurth, T., Schürks, M., Logroscino, G. & Buring, J. E. Migraine frequency and risk of cardiovascular disease in women. Neurology 73, 581–588 (2009).

Westergaard, M. L. S. et al. The headache under-response to treatment (HURT) questionnaire: assessment of utility in headache specialist care. Cephalalgia 33, 245–255 (2013).

Al Jumah, M. et al. HURT (Headache Under-Response to Treatment) questionnaire in the management of primary headache disorders: reliability, validity and clinical utility of the Arabic version. J. Headache Pain 14, 16 (2013).

Lipton, R., Manack, A., Serrano, D. & Buse, D. Acute treatment optimization for migraine: results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. J. Headache Pain 14, P201 (2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K.E., H.A. and M.A. researched data for the article. All authors made substantial contributions to discussion of the content, contributed to writing and reviewed and edited the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S.K. has been an invited speaker for Novartis. H.-C.D. has received honoraria for participation in clinical trials, contribution to advisory boards or oral presentations from Alder, Allergan, Amgen, Electrocore, Ipsen, Lilly, Medtronic, Novartis, Pfizer, Teva and Weber & Weber. Electrocore has provided financial support for his research projects. The German research council (DFG), the German ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and the European Union support his headache research. He also serves on the editorial boards of Cephalalgia and Lancet Neurology, chairs the clinical guidelines committee of the German Society of Neurology and is a member of the Clinical Trials Committee of the International Headache Society. D.D.M. has received honoraria, research and travel grants from Allergan, Amgen, Biogen, Cefaly, Eli Lilly, Electrocore, Mertz, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, Specifar and Teva. A.J.S. reports personal fees from Allergan and Novartis, grants from Novartis, and grants and personal fees from Invex Therapeutics. He is a trustee of the board of the International Headache Society and a member of the Council of the European Headache Federation. P.P.-R. has received honoraria as a consultant and speaker for Allergan, Almirall, Biohaven, Chiesi, Eli Lilly, Medlink, Medscape, Neurodiem, Novartis and Teva. Her research group has received research grants from Allergan, AGAUR, la Caixa foundation, EraNET Neuron, FEDER RISC3CAT, Migraine Research Foundation, Instituto Investigación Carlos III, MICINN, Novartis and PERIS, and has received funding for clinical trials from Alder, Amgen, Electrocore, Eli Lilly, Novartis and Teva. She is the founder of www.midolordecabeza.org, a trustee of the board of the International Headache Society and a member of the Council of the European Headache Federation. She is on the editorial board of Revista de Neurologia, an associate editor for Cephalalgia, Frontiers of Neurology and Journal of Headache and Pain. She is also a member of the Clinical Trials Guidelines Committee of the International Headache Society and has edited the Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Headache of the Spanish Neurological Society. P.M. has served on advisory boards for Allergan, Lilly, Novartis and Teva. He has received royalties from Springer Nature and travel support from the European Medicines Agency, and serves as Editor-in-Chief for Journal of Headache and Pain. A.D. reports consultant fees from Eli Lilly, Novartis and Teva. She also serves as President of the French Headache Society. M.L.-M. reports personal fees for advisory boards, speaker panels or investigation studies from Allergan, Amgen, Astellas, ATI, BMS, Boehringer, Boston Scientific, CoLucid, Convergence, GlaxoSmithKline, Grunenthal, Lilly, Medtronic, Menarini, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, ReckittBenckiser, Saint-Jude, Sanofi-Aventis, Teva, UCB and Zambon. M.S.d.R. reports consultant fees as a speaker or participation on advisory boards from Allergan, Eli-Lilly, Novartis and Teva. G.M.T. reports consultant fees from Amgen, Eli Lilly, Novartis and Teva, and has received grant support from the Dutch Brain Foundation, Dutch Heart Foundation, NIH, NOW and ZonMW. K.P. has received honoraria as a speaker and/or consultant, and/or received research support from Allergan, Amgen/Novartis, Autonomic Technologies, Eli-Lilly and Teva. S.S. reports fees as a speaker or consultant for Allergan, Abbott, Eli-Lilly, Novartis and Teva. She is also an associate editor for Stroke and serves as co-editor for Journal of Headache and Pain. U.R. has received consulting fees, speaking or teaching fees and/or research grants from Allergan, Amgen, Autonomic Technologies, CoLucid, ElectroCore and Novartis. H.W.S. has received consultant fees for lectures from Eli-Lilly, Novartis and TEVA. He has received consultant fees for advisory board participation from Balancair and Eli Lilly, and has received funding from Novartis. Z.K. has been a speaker and/or consultant, and/or received research support from Allergan, Amgen/Novartis, Ely-Lilly, Merck and Teva. T.J.S. reports personal fees from Eli Lilly. M.A. has received personal fees from Alder BioPharmaceuticals, Allergan, Amgen, Eli-Lilly, Novartis and Teva. He has been or is currently a principal investigator on clinical trials for Alder, Amgen, ElectroCore, Novartis and Teva. He serves as Associate Editor of Cephalalgia, Headache and Journal of Headache and Pain. He also reports research grants from Lundbeck Foundation, Novo Nordisk Foundation, and Research Foundation of the Capital Region of Denmark. The other authors report no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Neurology thanks J. Rothrock, A. Tinsley and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Related links

Example headache calendar: https://static-content.springer.com/esm/art%3A10.1186%2Fs10194-018-0899-2/MediaObjects/10194_2018_899_MOESM17_ESM.pdf

Example headache diary: https://static-content.springer.com/esm/art%3A10.1186%2Fs10194-018-0899-2/MediaObjects/10194_2018_899_MOESM16_ESM.pdf

HURT questionnaire: https://migraine-acute-treatment.ime.springerhealthcare.com/wp-content/uploads/EN-HURT.pdf

Patient information leaflets: https://static-content.springer.com/esm/art%3A10.1186%2Fs10194-018-0899-2/MediaObjects/10194_2018_899_MOESM21_ESM.pdf

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eigenbrodt, A.K., Ashina, H., Khan, S. et al. Diagnosis and management of migraine in ten steps. Nat Rev Neurol 17, 501–514 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-021-00509-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-021-00509-5

This article is cited by

-

Safety and tolerability of atogepant for the preventive treatment of migraine: a post hoc analysis of pooled data from four clinical trials

The Journal of Headache and Pain (2024)

-

Unveiling the therapeutic potential of Dl-3-n-butylphthalide in NTG-induced migraine mouse: activating the Nrf2 pathway to alleviate oxidative stress and neuroinflammation

The Journal of Headache and Pain (2024)

-

Trends and prescribing patterns of antimigraine medicines in nine major cities in China from 2018 to 2022: a retrospective prescription analysis

The Journal of Headache and Pain (2024)

-

Healthcare utilisation and economic burden of migraines among bank employees in China: a probabilistic modelling study

The Journal of Headache and Pain (2024)

-

Cellular and Molecular Roles of Immune Cells in the Gut-Brain Axis in Migraine

Molecular Neurobiology (2024)