Abstract

In developing countries including Ethiopia stunting remained a major public health burden. It is associated with adverse health consequences, thus, investigating predictors of childhood stunting is crucial to design appropriate strategies to intervene the problem stunting. The study uses data from the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) conducted from January 18 to June 27, 2016 in Ethiopia. A total of 8117 children aged 6–59 months were included in the study with a stratified two stage cluster sampling technique. A Bayesian multilevel logistic regression was fitted using Win BUGS version 1.4.3 software to identify predictors of stunting among children age 6–59 months. Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with 95% credible intervals was used to ascertain the strength and direction of association. In this study, increasing child’s age (AOR = 1.022; 95% CrI 1.018–1.026), being a male child (AOR = 1.16; 95%CrI 1.05–1.29), a twin (AOR = 2.55; 95% CrI 1.78–3.56), having fever (AOR = 1.23; 95%CrI 1.02–1.46), having no formal education (AOR = 1.99; 95%CrI 1.28–2.96) and primary education (AOR = 83; 95%CrI 1.19–2.73), birth interval less than 24 months (AOR = 1.40; 95% CrI 1.20–1.61), increasing maternal BMI (AOR = 0.95; 95% CrI 0.93–0.97), and poorest household wealth status (AOR = 1.78; 95% CrI 1.35–2.30) were predictors of childhood stunting at individual level. Similarly, region and type of toilet facility were predictors of childhood stunting at community level. The current study revealed that both individual and community level factors were predictors of childhood stunting in Ethiopia. Thus, more emphasize should be given by the concerned bodies to intervene the problem stunting by improving maternal education, promotion of girl education, improving the economic status of households, promotion of context-specific child feeding practices, improving maternal nutrition education and counseling, and improving sanitation and hygiene practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stunting is a manifestation of severe, irreversible physical, physiological and cognitive impairment due to chronic malnutrition in the early life1,2.

Stunting causes the death of one million children each year in the world3. Globally, 151 million (22%) under-five children were stunted according to the recent report by UNICEF/ World Bank. Majority (91%) of stunted children were from poorest regions of the world i.e. South east Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa regions including Ethiopia4.

Even if the level of stunting is reduced across the world, the problem of stunting remained high in Africa. In Africa the number of stunted children is estimated to rise from 56 million in 2010 to 61 million by 20254.

Further, the majority of stunted children were found in Ethiopia5. In the country 40% children were stunted based on report from the 2014 mini Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS)6. In addition, based on EDHS 2016 report about 38% of stunted children were found in Ethiopia7.

Childhood stunting is linked to different adverse health consequences and irreversible damages. It is correlated with poor developmental attainment and intelligence in children8,9,10. There is also evidence that stunted children are less likely to enroll in school and increased the risk of mortality and susceptibility to infection4,11. Reduced productivity, increased risk of extra weight gain and chronic non-communicable diseases in later life were reported in previous studies10,11,12. Moreover, stunting increased obstetric risk and leads to low birth weight babies thus, have an intergenerational impact10,13.

According to studies done previously in different parts of Ethiopia large family size, multiple siblings, food insecurity, poor wealth status, inadequate health care utilization and sanitary practices, unavailability of latrine and unprotected source of water were significant predictors of childhood stunting14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. Stunting is also reported with children whose mothers are illiterate23. Male sex, frequent diarrheal episode and doesn’t receive vitamin A supplementation also increases the likelihood of stunting24,25,26,27.

Even though the government of Ethiopia adopted and implemented the national nutrition strategy, national nutrition program, and infant and young child feeding intervention programs to reduce the problem in the past few years, still stunting remained a major public health burden6,7,28,29,30.

However, previous studies done on stunting in different parts of Ethiopia more focused on individual level factors associated with stunting by employing basic regression models. In this study community level factors were included and addressed by using advanced mixed effect model which is appropriate for hierarchical DHS data. In addition, most of these studies were conducted in small localized areas and using small sample size which were not representative figure at the national level due to variations in socioeconomic, culture, awareness and practices in different parts of Ethiopia. But the current study used the national representative data in all regions of the country from Ethiopia Demographic Health Survey 2016 (EDHS) data to provide the national figure.

Furthermore, previous studies regarding predictors of stunting were used the classical/frequents statistical methods. In this study the Bayesian approach was used to estimate parameters of interest. Thus, employing Bayesian statistical method for parameters estimation is superior when multilevel logistic regression model is employed compared to the classical methods. Therefore, this study aims to investigate predictors of stunting among children aged 6–59 months in Ethiopia using multi-level analysis by applying Bayesian statistical approach which has powerful estimation for hierarchical data and generates evidence from prior information and the current data.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

A total of 8117 children age 6–59 months were included in the analysis. The median age of children were 31 months (IQR = 18–46). The mean maternal BMI was 20.70 kg/m2 with (SD ± 3.40). In addition, the mean height of mothers was 158 cm with (SD ± 6.7). Most of the study participants about, 7242 (89.22%) were rural residents.

Regarding family wealth index about 1901(23.42%) of respondents were from the poorest house.

Majority of children about, 7020 (86.49%) belongs to male household head. Regarding maternal education, nearly two third, 5388 (66.38%) of children had mothers who have no formal education.

In this study about, 3427 (42.96) of respondents were not anemic. Of the children, 7109 (87.59%) had no history of diarrhea and about, 4429 (54.57%) were not received vitamin A supplementation in the last 6 months.

Most of the households about, 7353 (90.59%) had not used improved toilet facilities, and about, 4582 (56.45%) of the households obtained water from improved sources (Table 1).

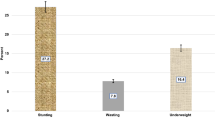

In this study the overall prevalence of stunting among children aged 6–59 months in Ethiopia was 41.20% (95% CI 40.16%, 42.25%), comprising of moderate stunting 22.41% (95% CI 21.54%, 23.31%) and severe stunting 18.79% (95% CI 18.00%, 19.64%).

Childhood stunting was more prevalent in males 1838 (44%) than females 1505 (38%). Also, the likelihood of stunting was highest in children from mothers who had no formal education 2388 (41%). Similarly the magnitude of stunting was higher among children from the poorest households 925 (49%) and who had mild anemia 130 (52.5%) (Table 2).

Predictors of stunting among children age 6–59 months in Ethiopia

In the Bayesian multi-level multivariate logistic regression analyses model both individual and community level factors were included.

Among individual level factors sex of child, child age, type of birth, anaemia status of the child, history of fever in the last 2 weeks, education level of the mother, maternal BMI, maternal height, birth interval, and family wealth index were identified as significant predictors of childhood stunting. Among community level factors included in the study only type of toilet facility and region were significant predictors of childhood stunting.

Individual level factors

The Bayesian multi-level multivariable logistic regression analysis result showed that being male children were 16% more (AOR = 1.16, 95% CrI 1.05–1.29) likely to be stunted as compared to female children.

Children of multiple birth (twin) was 2.55 times (AOR = 2.55, 95% CrI 1.78–3.56) more likely to be stunted as compared to their counterpart. Children who had fever were 23% (AOR = 1.23, 95% CrI 1.02–1.46) more likely to be stunted compared to the counterparts.

Children with mild anemia were three times (AOR = 3.13, 95% CrI 2.34–4.12), moderate anemia 81% (AOR = 1.81, 95% CrI 1.58–2.08), and severe anemia 37% (AOR = 1.37, 95% CrI 1.19–1.56) more likely to be stunted compared to children who were not anemic.

Children belonging to mothers who had no formal education were 99% (AOR = 1.99, 95% CrI 1.28–2.96), and primary education were 83% (AOR = 1.83, 95% CrI 1.19–2.73) more likely to be stunted compared to children whose mothers had higher education.

Children from poorest house hold wealth status were 78% (AOR = 1.78, 95% CrI 1.35–2.30), poorer household 73% (AOR = 1.73, 95% CrI 1.31–2.23), and middle household 37% (AOR = 1.37, 95% CrI 1.04–1.78) more likely to be stunted compared to children from richest household wealth status.

The odds of being stunted were 40% (AOR = 1.40; 95% CrI 1.20–1.61) higher among children with < 24 months birth interval compared to children having ≥ 24 months birth interval (Table 3).

Community level factors

The finding of this study indicated that type of toilet facility (i.e. unimproved) and region were significant predictors of childhood stunting at community level.

Those children from households who had unimproved toilet facility was 26% (AOR = 1.26; 95% CrI 1.05–1.54) more likely to be stunted compared to children from household who had access to improved toilet facility.

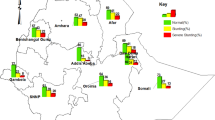

Similarly region was also found to be significant predictors of childhood stunting. Hence the likelihood of stunting among children living in Dire-Dawa were 2.34 (AOR = 2.34; 95% CrI 1.41–3.67), Afar 1.85 (AOR = 1.85; 95% CrI 1.13–2.87), Amhara 2.81 (AOR = 2.81; 95% CrI 1.73–4.33), Benishangul-Gumuz 2.46 (AOR = 2.46; 95% CrI 1.50–3.83), Harari1.93 (AOR = 1.93; 95% CrI 1.01–3.42), Oromia 1.86 (AOR = 1.86; 95% CrI 1.03–1.78), SNNPR 2 (AOR = 2.01; 95% CrI 1.25–3.06), and Tigray 2.1 (AOR = 2.05; 95% CrI 1.28–3.13) times higher compared to children live in Addis Ababa (Table 3).

Methods

Study area and period

The 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) is the fourth Demographic and Health Survey conducted in Ethiopia, which was conducted from January 18, 2016 to June 27, 2016. The sampling frame used for the 2016 EDHS is the Ethiopia Population and Housing Census (PHC), which was conducted in 2007 by the Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency. The census frame is a complete list of 84,915 enumeration areas (EAs) created for the 2007 PHC. An EA is a geographical area covering on average 181 households7.

Study design

A Community-based cross-sectional study design was conducted among children aged 6–59 months.

Population and sample

All children aged 6–59 months resided in Ethiopia (nine regions and two city administrations) were the source population and the study population was all children aged 6–59 months who were living in the selected households of Ethiopia. A total of 8117 children age 6–59 months which fulfil the inclusion criteria were included in the analysis.

A stratified two-stage cluster sampling procedure was employed where enumeration areas (EA) were the sampling units for the first stage and households for the second stage. In the 2016 EDHS, a total of 645 EAs (202 urban and 443 rural) were selected with a probability proportional to EA size (based on the 2007 housing and population census) and independent selection in each sampling stratum. Of these, 18,008 households and 16,583 eligible women were included. The detailed sampling procedure was presented in the full EDHS report7 indicated in the Fig. 1 below.

Data collection procedure and variables

Stunting among children 6–59 months age was the dependent variable of the study. The independent variables were community level factors (region, clusters, residence, source of drinking water, and type of toilet facility), household factors (wealth index, household head family size, and number of under five children in the house hold), maternal factors(educational level, marital status, body mass index (BMI), maternal height, ANC visit, and birth interval), and child factors (age, sex, birth type, birth order, birth weight, diarrhea, acute respiratory tract infection (ARI), fever, vitamin A supplementation, and anemia status).

Stunting is defined as children who have low height/length-for-age-Z score < − 2 SDs of the median value of the WHO Child Growth Standards median aged 6–59 months1,31.

Improved drinking water source includes piped water, public tap, standpipes, tube wells, boreholes, protected dug wells and spring, rain water, and bottled water32. Improved toilet facility includes any non-shared toilet of those types: flush/pour flush toilets to piped water systems, septic tanks and, and pit latrines; ventilated improved pit (VIP) latrines, pit latrines with slabs, and composting toilets32. Unimproved toilet facility includes flush to somewhere else, flush do not know where, pit latrine without slab/open pit, no facility/bush/field, bucket toilet, hanging toilet/latrine, others32.

Anemia level was determined based on hemoglobin levels adjusted for altitude in enumeration areas that are above 1000 m. They are classified as not anemic if the hemoglobin level is ≥ 11.0 mg/dl, mild anemic if hemoglobin level is from 10.0–10.9 mg/dl, moderate anemic if the level of hemoglobin is from 7.0–9.9 mg/dl, and severe anemic if the level of hemoglobin is < 7.0 mg/dl)7.

Body mass index (BMI) for women aged 15–49 years who are not pregnant and who have not had a birth in the last 2 months before the survey was determined by divided weight in kilograms by height in meters square (kg/m2). Accordingly classified as under-weight/thin (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal (BMI in the range of 18.5–24.9 kg/m2) and over-weight (BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m2)7.

Anthropometric measurements

The length of children aged < 24 months was measured during the EDHS in a recumbent position to the nearest 0.1 cm using a locally made measuring board (Shorr Board) with an upright wooden base and moveable headpieces. Children ≥ 24 months were measured while standing upright. The length/height-for-age Z-score, an indicator of nutritional status, was compared with reference data from the WHO Multicenter Growth Reference Study Group, 200633. Children whose height-for-age Z-score is < − 2 SD from the median of the WHO reference population are considered stunted (short for their age).

Weight measurement was taken after children were undressed (no shoe, dresses and wet hat). For a child who stands on the weighing scale calmly, the measurement was taken in the nearest 0.1 kg. In the time of refuse to be scaled, children’s mother carried and stood on the scale. Finally, the child actual weight was registered by subtracting mother’s weight from mother and child weight7.

Before the actual data collection, interviewers were trained and a pre-test was performed. Interviews were also performed using local languages. A structured and pre-tested questionnaire was used as a tool for data collection. The 2016 EDHS interviewers used tablet computers to record responses during interviews. The tablets were equipped with Bluetooth technology to enable remote electronic transfer of files (transfer assignment sheets from team supervisors to interviewers and transfer of completed copies from interviewers to supervisors)7.

Data management and analysis

The data set was available at the DHS website https://www.dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm. After registering for the permission it was accessed through the DHS website; https://dhsprogram.com/data/dataset_admin/login_main.cfm. The kid recode (KR) data set in STATA file contains the outcome and predictor variables of the study. The data was explored, cleaned, coded, re-categorized and recoded. Then, the data was prepared in text file for analysis using publicly available software Win BUGS. Finally, in the Win BUGS program the distributional form of the data and the parameters were specified. Model specification in terms of the distributional relationships between observables and parameters (likelihood) and prior distributions of parameter, auxiliary files containing the data and initial values for unknowns were input to Win BUGS.

This study was based on secondary data analysis of 2016 EDHS by adjusting sample weights. Categorical characteristics and outcome of the study was described in terms of percentage and frequencies. Tables were used to present the result. A Bi-variable multi-level logistic regression analysis was carried out to see the crude effect of each independent variable on stunting, and then variables with P < 0.2 were entered to the multivariable multi-level logistic regression analysis34.

The Bayesian multi-level logistic regression model was employed using Win BUGS statistical software package version 1.4.3 (MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge and Imperial College London, UK) to identify predictors of stunting. WinBUGS is a windows-based computer program designed to conduct Bayesian Analyses of complex statistical models using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods. The parameter estimation was done with MCMC simulation method by using Gibbs sampling technique. Non informative priors for fixed and random effect parameters were selected and three different initial values for these parameters were specified. Model specification with binary multi-level logistic regression was checked, data were loaded that were presented with rectangular text file format. Initial values compiled with the model and initialized.

The deviance information criterion (DIC) statistic35,36 was calculated for the different models (individual level, community level and both individual and community level) fitted with logit, probit and cloglog link functions. The DIC was used to evaluate and compare model performance of the full model and the reduced model. A model with lower DIC was considered as one with a better fit.

Convergence of parameters was checked visually using history plots, kernel density, auto correlation plots and Gulman-Rubin convergence diagnostic. Summary statistic (mean, SD, AOR and 95% credible intervals for parameters) from the posterior distribution of the parameters was calculated from simulated samples.

Variance partition coefficient (VPC) statistic was calculated to measure the variation between clusters (the random effect variable)37. It represents the percentage variance explained by higher level clusters. Hence, it was calculated as below:

where \(\sigma_{u}^{2}\) is the between cluster variance, \(\sigma_{e}^{2} \) = 3.2.

Ethical issues

Ethical clearance was gained from the ethical review board of Institute of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar. Written consent was obtained from Measure DHS International Program which approved the data-sets. All the data used in this study are publicly available, aggregated secondary data with not having any personal identifying information that can be linked to particular individuals, communities, or study participants. Confidentiality of data was maintained anonymously.

Confirmation of methods

Author(s) confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations in the manuscript.

Discussion

The study demonstrated that child’s age was significant predictors of childhood stunting. That is the older the child the higher the risk of being stunted. This finding is in line with studies done in Ethiopia and other developing countries38,39,40,41,42. This could be due to the fact that stunting is a chronic malnutrition and is commonly noticed long term nutritional deprivation. The older children are being weaned off breast feeding and also they are becoming mobile and get contaminated materials such as water, food, and soil then take into their mouth. These conditions expose children to infection which decreases food intake43,44.

Our study showed that male children were more stunted compared to female children. It is similar with reports from different regions38,40,41,45,46. The justification may be related that in early life childhood morbidity is higher among males than females. In addition, it is related with the higher number of male preterm births as compared to female preterm births that lead to increase stunting in under-five children47. In contrast to this finding studies demonstrated female children were more stunted compared to male children48. But this discrepancy could not be important to design interventions, because sex is not modifiable factor.

Educational level of the mother showed a significant negative association with stunting among under-five children. This finding is similar with previous reports that maternal education has a positive outcome in reducing the child stunting40,41,45,48,49. One possible explanation is that knowledge that mothers get from their formal education could capable them to practice nutritional and other related behaviors that prevent chronic malnutrition/stunting. In addition to this, educated mothers have better health seeking behavior for childhood illnesses as compared to uneducated mothers50. A higher maternal education leads to better health care practice, acceptance of modern health practices and higher female autonomy, that affects health-related decisions again increases nutritional effects51. Further, education is one of an important tool for improvement of income which helps them to satisfy nutritional requirements. Furthermore, education increases skills and is highly linked with different socio-economic factors including life style, income, and fertility at individual and community level8.

In this study, maternal nutritional status was significant predictors of childhood stunting. Studies done in Ethiopia and Nigeria reported similar findings39,40,44,52. Maternal BMI is an essential predictor of childhood stunting and affected by maternal nutrition, hence proper nutrition for mothers during prenatal and postnatal period is highly demanded to enhance the growth of children. Maternal under-nutrition which leads poor growth of fetus leading to intrauterine growth retardation, this in turn strongly related with childhood stunting39,53.

Likewise, maternal height was found significant predictor of childhood stunting. The finding was consistent with studies done in India and Cambodia54,56. This could be explained by short maternal stature is associated with intrauterine growth retardation and low birth weight which are in turn predictors of impaired child growth57.

In addition, having birth interval < 24 months increases the likelihood of stunting. The finding is consistent with the previous studies39,40,55. The possible explanation could be those who had a short birth interval between births could be followed by adverse consequence on child nutrition because of it undermines intrauterine growth and caring quality of the child58.

The economic status of the households is related with nutritious foods at the household level which could determine the growth and the development of the children in early life59. The result of this study showed that children with households in the poorest wealth quintiles were more likely to be stunted than children with richest wealth index, which is consistent with the previous studies40,42,45. It is clear that, increased income improves dietary diversity, which in turn improves nutrient intake and nutritional status of the children and the mother, and it will result appropriate growth and development60,61.

From this study finding, children being twin were positively associated with stunting. This finding is in line with studies done in Cambodia55. However, the result is contradicting to studies done in India which showed being twin and stunting had negative association62,63. This might be due to socio-cultural differences in child care practices of the countries.

Children having fever were more likely to being stunted as compared to those children who had no fever. This may be due to the fact that during illness children have reduced intake of food and in turn affects their body nutrients requirement. Also, this study finding was opposite to studies done in Kenya, Nepal and Colombia that showed negative association between childhood stunting and fever64,65,66.

This study also showed that the likelihood of stunting was higher among children from households who had unimproved toilet facility compared to children from households who had improved toilet facility. This finding is consistent with findings from studies in Sub-Saharan Africa and Cambodia39,55. It is explained that children become more affected by environmental contamination when they start crawling, walking, exploring and taking objects to their mouth, that increases the risk of infection. This leads to diarrheal illness which in turn deteriorates nutritional status of children67. In this study region was found to be significant predictors of childhood stunting. Accordingly, children living in Dire-dawa, Amhara, Afar, Tigray, SNNPR, Oromia, and Benishangul Gumuz regions were more likely to be stunted compared to children living in Addis-Ababa. This finding is supported by studies conducted in Ethiopia40. In Ethiopia there are socio-cultural and socio-economic differences among regions, which influence the household food security, which in turn affect the risk of childhood stunting. In addition, the amount and distribution of rainfall and temperature influences household food availability, thus increasing the risk of a child to be stunted68.

Using Bayesian statistical analysis, which has high power and computes the posterior distribution which precludes the prior information with the current data and inference is based on the posterior distribution. Moreover, the use of multilevel logistic regression analysis, which was able to identify other factors beyond individual level factor that would not be identified by using standard logistic regression analysis, and a nationally representative population based study that could be made inference for all children in Ethiopia were the strength of study.

As a limitation the study didn’t include important variables such as quantitative dietary consumption behavioral factors to substantiate the findings. In addition the study did not address the causal effects, since it was based on data from cross-sectional.

The findings of the study contributes knowledge to the new statistical approach (Bayesian inference) for researchers and guide public health planners and policy makers and other concerned bodies to design appropriate intervention programs including improving maternal education, promotion of girl education, improving the economic status of households, promotion of context-specific child feeding practices, improving maternal nutrition education and counseling, improving sanitation and hygiene practices to intervene the problem of stunting. In general, these findings are of supreme importance for the Ministry of Health, health bureaus, and partners to develop nutritional programs to reduce childhood stunting.

Conclusion

In this study, both individual and community level factors were significant predictors of childhood stunting. Accordingly, increased child’s age, being a male child, a twin, children with anemia, having fever, have no formal education and primary education of the mother, short birth interval (< 24 months) and lived in middle or lowest household wealth status were predictors increased the likelihood of childhood stunting at the individual level. On the other hand, increased maternal BMI and maternal long stature were factors that reduced the odds of childhood stunting at the individual level. Using unimproved toilet facility and living in Dire-dawa, Amhara, Afar, Tigray, SNNPR, Oromia, and Benishangul Gumuz regions increases the likelihood of childhood stunting at community level.

Data availability

Data is available online from http://www.measuredhs.com. A letter of approval for the use of the data was obtained from the Measure DHS and the data set was downloaded from the website (https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm). This study used EDHS 2016 child data set and extracted the outcome and explanatory variables.

References

UNICEF. UNICEF Data:Monitoring the situation of Children and women. Malnutrition, 2018. Retrieved from http://data.unicef.org/nutrition/malnutrition.html.

World Bank Group et al. Reaching the global target to reduce stunting: How much will it cost and how can we pay for it?. Breastfeeding Med. 11(8), 413–415. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2016.0128 (2016).

UNICEF. Stop Stunting: Progress Report 2013–2015. Unicef, 2015. Global Reference List of 100 Core Health Indicators (plus health-related SDGs). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

UNICEF/WHO/World Bank. Levels and trends in child malnutrition: UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Group Joint Malnutrition Estimates (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0266-6138(96)90067-4.

IFPRI. Global Nutrition Report 2016: From Promise to Impact: Ending Malnutrition by 2030. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). 2016.

Agency CS. Ethiopia mini demographic and health survey 2014. 2014.

ICF CSACEa. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey. 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF (2016)

Lasky, R. E. et al. The relationship between physical growth and infant behavioral development in rural Guatemala. Child Dev. 52, 219–226 (1981).

Jesmin, A., Yamamoto, S. S., Malik, A. A. & Haque, M. A. Prevalence and determinants of chronic malnutrition among preschool children: A cross-sectional study in Dhaka City, Bangladesh. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 29(5), 494 (2011).

Moock, P. R. & Leslie, J. Schooling in the Terai region. J. Dev. Econ. 20, 33–52 (1986).

Grantham-McGregor, S. et al. Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. Lancet 369(9555), 60–70 (2007).

Kar, B. R., Rao, S. L. & Chandramouli, B. Cognitive development in children with chronic protein energy malnutrition. Behav. Brain Funct. 4(1), 31 (2008).

Blössner, M., De Onis, M. & Prüss-Üstün, A. Malnutrition: Quantifying the health impact at national and local levels (WHO, Geneva, 2005).

Fikadu, T., Assegid, S. & Dube, L. Factors associated with stunting among children of age 24 to 59 months in Meskan district, Gurage Zone, South Ethiopia: A case–control study. BMC Public Health 14(1), 800 (2014).

Tamiru, M., Tolessa, B. & Abera. S. Under nutrition and associated factors among under-five age children of Kunama ethnic groups in Tahtay Adiyabo Woreda. Tigray Regional State, Ethiopia: Community Based Study, 277–288 (2015)

Tariku, A. et al. Nearly half of preschool children are stunted in Dembia district, Northwest Ethiopia: A community based cross-sectional study. Arch. Public Health 74(1), 13 (2016).

Disha, A., Rawat, R., Subandoro, A. & Menon, P. Infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices in Ethiopia and Zambia and their association with child nutrition: Analysis of demographic and health survey data. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 12(2), 5895–5914 (2012).

Roger, S. & Yongyout, K. Analyzing the causes of child stunting in DPRK. UNICEF for every children Democratic People’s Republic of Korea report. Further analysis of 2002 UNICEF nutrition assessment report, pp 1–36 (2003).

Vitolo, M. R., Gama, C. M., Bortolini, G. A., Campagnolo, P. D. & Drachler, M. L. Some risk factors associated with overweight, stunting and wasting among children under 5 years old. J. Pediatr. 84(3), 251–257 (2008).

Kamal, S. Socio-economic determinants of severe and moderate stunting among under-five children of rural Bangladesh. Malays. J. Nutr. 17(1), 105–118 (2011).

Derso, T., Tariku, A., Biks, G. A. & Wassie, M. M. Stunting, wasting and associated factors among children aged 6–24 months in Dabat health and demographic surveillance system site: A community based cross-sectional study in Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 17(1), 96 (2017).

Chirande, L. et al. Determinants of stunting and severe stunting among under-fives in Tanzania: Evidence from the 2010 cross-sectional household survey. BMC Pediatr. 15(1), 165 (2015).

Agedew, E. & Chane. T. Prevalence of stunting among children aged 6–23 months in Kemba Woreda, Southern Ethiopia: A community based cross-sectional study. Adv. Public Health. 2015 (2015).

Agho, K. E., Inder, K. J., Bowe, S. J., Jacobs, J. & Dibley, M. J. Prevalence and risk factors for stunting and severe stunting among under-fives in North Maluku province of Indonesia. BMC Pediatr. 9(1), 64 (2009).

Asfaw, M., Wondaferash, M., Taha, M. & Dube, L. Prevalence of undernutrition and associated factors among children aged between six to fifty nine months in Bule Hora district, South Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 15(1), 41 (2015).

Paudel, R., Pradhan, B., Wagle, R., Pahari, D. & Onta, S. Risk factors for stunting among children: a community based case control study in Nepal. Kathmandu Univ. Med. J. 39(3), 18–24 (2012).

Tariku, A., Biks, G. A., Derso, T., Wassie, M. M. & Abebe, S. M. Stunting and its determinant factors among children aged 6–59 months in Ethiopia. Ital. J. Pediatr. 43(1), 112 (2017).

Ethiopia fDRo. National Nutrition Strategy (2008).

Macro, O. Central Statistical Agency: Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2005 (ORC Macro, Calverton, 2006).

Macro, O. Central Statistical Agency: Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2005 (ORC Macro, Calverton, 2011).

De Onis, M. et al. Comparison of the World Health Organization (WHO) Child Growth Standards and the National Center for Health Statistics/WHO international growth reference: Implications for child health programmes. Public Health Nutr. 9(7), 942–947 (2006).

World Health Organization, Supply WUJW, Programme SM. Progress on sanitation and drinking water: 2015 update and MDG assessment: World Health Organization (2015).

WMGRS Group. Complementary feeding in the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study. Acta Paediatr. 450, 27 (2006).

Bendel, R. B. & Afifi, A. A. Comparison of stopping rules in forward “stepwise” regression. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 72(357), 46–53 (1977).

Chan, J. C. & Grant, A. L. Fast computation of the deviance information criterion for latent variable models. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 100, 847–859 (2016).

Berg, A., Meyer, R. & Yu, J. Deviance information criterion for comparing stochastic volatility models. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 22(1), 107–120 (2004).

Goldstein, H., Browne, W. & Rasbash, J. Partitioning variation in multilevel models. Underst. Stat. Stat. Issues Psychol. Educ. Soc. Sci. 1(4), 223–231 (2002).

Demissie, S. & Worku, A. Magnitude and factors associated with malnutrition in children 6–59 months of age in pastoral community of Dollo Ado district, Somali region, Ethiopia. Sci. J. Public Health 1(4), 175–183 (2013).

Akombi, B. et al. Stunting, wasting and underweight in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14(8), 863 (2017).

Haile, D., Azage, M., Mola, T. & Rainey, R. Exploring spatial variations and factors associated with childhood stunting in Ethiopia: Spatial and multilevel analysis. BMC Pediatr. 16(1), 49 (2016).

Wamani, H., Tylleskär, T., Åstrøm, A. N., Tumwine, J. K. & Peterson, S. Mothers’ education but not fathers’ education, household assets or land ownership is the best predictor of child health inequalities in rural Uganda. Int. J. Equity Health 3(1), 9 (2004).

Tamiru, M., Tolessa, B. E. & Abera, S. Under nutrition and associated factors among under-five age children of Kunama ethnic groups in Tahtay Adiyabo Woreda, Tigray Regional State, Ethiopia: Community based study. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 4(3), 277–288 (2015).

World Health Organization. Progress on sanitation and drinking water: 2014 update (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2014).

Dewey, K. G. & Brown, K. H. Update on technical issues concerning complementary feeding of young children in developing countries and implications for intervention programs. Food Nutr. Bull. 24(1), 5–28 (2003).

Kavosi, E. et al. Prevalence and determinants of under-nutrition among children under six: A cross-sectional survey in Fars province, Iran. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 3(2), 71 (2014).

Teshome, B., Kogi-Makau, W., Getahun, Z. & Taye, G. Magnitude and determinants of stunting in children underfive years of age in food surplus region of Ethiopia: The case of west gojam zone. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 23(2), 98–106 (2009).

Elsmén, E., Pupp, I. H. & Hellström-Westas, L. Preterm male infants need more initial respiratory and circulatory support than female infants. Acta Paediatr. 93(4), 529–533 (2004).

Abeway, S., Gebremichael, B., Murugan, R., Assefa, M. & Adinew, Y. M. Stunting and its determinants among children aged 6–59 months in northern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. J. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 1078480 (2018).

Abuya, B. A., Ciera, J. & Kimani-Murage, E. Effect of mother’s education on child’s nutritional status in the slums of Nairobi. BMC Pediatr. 12(1), 80 (2012).

Assefa, T., Belachew, T., Tegegn, A. & Deribew, A. mothers’health care seeking behavior for childhood illnesses in Derra District, Northshoa Zone, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 18(3), 87–93 (2008).

Akombi, B., Agho, K., Merom, D., Hall, J. & Renzaho, A. Multilevel analysis of factors associated with wasting and underweight among children under-five years in Nigeria. Nutrients 9(1), 44 (2017).

Mamiro, P. S. et al. Feeding practices and factors contributing to wasting, stunting, and iron-deficiency anaemia among 3–23-month old children in Kilosa district, rural Tanzania. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 23, 222–230 (2005).

Lartey, A. Maternal and child nutrition in Sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and interventions. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 67(1), 105–108 (2008).

Rah, J. H. et al. Household sanitation and personal hygiene practices are associated with child stunting in rural India: A cross-sectional analysis of surveys. BMJ Open 5(2), e005180 (2015).

Ikeda, N., Irie, Y. & Shibuya, K. Determinants of reduced child stunting in Cambodia: Analysis of pooled data from three Demographic and Health Surveys. Bull. World Health Organ. 91, 341–349 (2013).

Özaltin, E., Hill, K. & Subramanian, S. Association of maternal stature with offspring mortality, underweight, and stunting in low-to middle-income countries. JAMA 303(15), 1507–1516 (2010).

Murray, C. J. et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380(9859), 2197–2223 (2012).

Dewey, K. G. & Cohen, R. J. Does birth spacing affect maternal or child nutritional status? A systematic literature review. Matern. Child Nutr. 3(3), 151–173 (2007).

Tingay, R. S. et al. Food insecurity and low income in an English inner city. J. Public Health 25(2), 156–159 (2003).

Taruvinga, A., Muchenje, V. & Mushunje, A. Determinants of rural household dietary diversity: The case of Amatole and Nyandeni districts, South Africa. Int. J. Dev. Sustain. 2(4), 2233–2247 (2013).

Doan, D. Does income growth improve diet diversity in China? (2014).

Fenske, N., Burns, J., Hothorn, T. & Rehfuess, E. A. Understanding child stunting in India: A comprehensive analysis of socio-economic, nutritional and environmental determinants using additive quantile regression. PLoS ONE 8(11), e78692 (2013).

Gewa, C. A. & Yandell, N. Undernutrition among Kenyan children: Contribution of child, maternal and household factors. Public Health Nutr. 15(6), 1029–1038 (2012).

Dekker, L. H., Mora-Plazas, M., Marín, C., Baylin, A. & Villamor, E. Stunting associated with poor socioeconomic and maternal nutrition status and respiratory morbidity in Colombian schoolchildren. Food Nutr. Bull. 31(2), 242–250 (2010).

Bloss, E., Wainaina, F. & Bailey, R. C. Prevalence and predictors of under-weight, stunting, and wasting among children aged 5 and under in western Kenya. J. Trop. Pediatr. 50(5), 260–270 (2004).

Gurung, C. & Sapkota, V. Prevalence and predictors of underweight, stunting and wasting in under-five children. J. Nepal Health Res. Council (2010).

Pruss-Ustun, A. Safer Water, Better Health: Costs, Benefits and Sustainability of Interventions to Protect and Promote Health (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2008).

Gebreyesus, S. H., Lunde, T. M., Mariam, D. H., Woldehanna, T. & Lindtjørn, B. Climate change, crop production and child under nutrition in Ethiopia; a longitudinal panel study. Spatial variations in child undernutrition in Ethiopia: Implications for intervention strategies (2014).

Acknowledgements

First of all, we would like to thank the Measure DHS International Program for their willingness to access the data set of the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey and release the dataset with confirmation letter for this research work. We would also like to thank all personnel involved for the accomplishment of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M.; conceived of the study, coordinate data collection. A.M., L.D., A.G. and E.T. performed statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Muche, A., Gezie, L.D., Baraki, A.Ge. et al. Predictors of stunting among children age 6–59 months in Ethiopia using Bayesian multi-level analysis. Sci Rep 11, 3759 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-82755-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-82755-7

This article is cited by

-

Socio-economic, demographic, and contextual predictors of malnutrition among children aged 6–59 months in Nigeria

BMC Nutrition (2024)

-

Mapping stunted children in Ethiopia using two decades of data between 2000 and 2019. A geospatial analysis through the Bayesian approach

Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition (2023)

-

Gender-specific disaggregated analysis of childhood undernutrition in Ethiopia: evidence from 2000–2016 nationwide survey

BMC Public Health (2023)

-

Association between water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and child undernutrition in Ethiopia: a hierarchical approach

BMC Public Health (2022)

-

Determinants of food preparation and hygiene practices among caregivers of children under two in Western Kenya: a formative research study

BMC Public Health (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.