Key Points

-

Explores the policy context for the greater use of skill mix in dentistry.

-

Introduces a new workforce planning model based on four components: productivity, level of service, epidemiology and population demographics.

-

Discusses the different risks and opportunities pursuant to the debate on the greater use of substitution and supplementation in general dental practice.

Abstract

Workforce planning is essential if the future capacity of a state funded system and the supply of clinicians is to match the future need for care. Important aspects of this process are exploring the influences on productivity and the level of service that is necessary for a state funded system. Labour substitution has a direct impact upon the productivity of the workforce, yet the use of skill mix in dentistry is an area where the dental profession has lagged behind their medical colleagues. This brief paper explores the policy context for labour substitution, highlighting key barriers to its integration, potential drivers for change and future areas for research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Workforce planning is about 'ensuring the right number of people with the right skills are in the right place at the right time to provide the right services to the right people'.1 Despite recommendations from the World Health Organisation (WHO) to adopt a systems approach when considering healthcare provision,2 there is a dearth of literature on the complexity of factors that influence workforce planning in dentistry.

This is essential in any state funded system like the National Health Service (NHS), which both trains and employs future clinicians.

The two most common models of workforce planning used across the healthcare sector are the 'stock and flow'3 [1] and the demographic approach [2].4 The former balances future losses from a system (Ll) against recruitment and retention (Ln), while the latter simply 'grosses up' current provision based on changes to population demographics (Pt+n).

Such approaches ignore the impact of changing health and confuse demand with population need. On the supply side, they also assume that there will be no changes to working practice in respect of service levels and service delivery, developments in medical technology are negligible and that changes in evidence to suggest treatments are not effective or are not relevant.4

Birch introduced a needs based population approach in 2007 [3].4 Here, future labour requirements are seen as a function of productivity (N / Q), level of service to deliver health (Q / H), the epidemiology of the common diseases (H / P) and population demographics (P).

More simply, future labour requirements are equivalent to the product of productivity, represented by the first term and the need for services, represented by the remaining terms. Both are heavily influenced by the prevailing policy context and the professional culture within which the service is delivered.

Productivity

Across the whole of the workforce in NHS dentistry, the main risks for productivity include: an increasing feminisation of the workforce leading to a reduction in workforce participation;5,6 changes in attitudes to professional practice among young graduates to match personal values leading to reduced participation;7,8,9 uncertainty over the impact of ethnicisation;10,11,12 loss to private practice and the absence of levers to ensure retainment;13 and a limited capital infrastructure; and migration.14

The use of skill mix for labour substitution directly impacts upon the productivity of the workforce, yet it is an area where the dental profession has lagged behind their medical colleagues.15 Nurses or auxiliary staff can either supplement or substitute the services provided by doctors, depending on their skill base and legislated scope of practice.16 Unlike medicine, the General Dental Council (GDC) is the professional regulatory body for both general dental practitioners (GDPs) and dental care professionals (DCPs) in the United Kingdom. This means there is limited autonomy for DCPs and a lack of professional independence.17,18 Working practices are also strictly defined, despite DCPs being technically able to undertake much of the day-to-day operative procedures. In addition, although DCPs are required to have their own professional indemnity,19,20 GDPs are vicariously liable for acts and omissions of their staff as employers under the NHS contract.

Studies in medicine have also suggested that the quality of services provided by labour substitution does not deteriorate,21,22 however, improvements in productivity are only possible when the referring clinician refrains from undertaking the delegated tasks, otherwise supplementation occurs.23,24 This requires good leadership and team management25 and creates challenges for the coordination of care, training, regulation and the management of change. The use of skill mix also increases transaction costs, with time being lost in the referral process. Such transaction costs need to be less than the costs saved through substitution. Knowledge of their scope of practice, perceptions about patient acceptance and the need for adequate management and supervision have all been identified as barriers to labour substitution in dentistry.26,27,28,29,30,31

Although hygienists appear to be a well accepted member of the dental team,26,27 financial considerations appear to play a significant part in the decision to use a therapist.26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36 A critical difference between medicine and dentistry is that GDPs run their practices as businesses to offset the cost of the capital risk of the premises and the equipment that they own, while ensuring liquidity to cover their overheads.37 This means that the use of labour substitution must be profitable and is sensitive to the remuneration system.38,39 Of the few studies that have examined therapists' profitability, patient charges generated did not cover the cost associated with their use.40 The move to dual qualification may offset this as many therapists are currently being employed as hygienists, but this means that they are not being utilised across the full range of their skills.41

In medicine, transaction costs can be offset by economies of scale, which enable a broader range of services to be made available.42 However, historically the size of dental practices has been limited to a small number of surgeries, with approximately a third being single-handed.43 This means that a sound business case is required to encourage investment in the greater use of skill mix. Given the lack of a capital infrastructure, it also means that the NHS has a limited number of levers to affect change other than through financial incentives.

Larger team sizes have been shown to impact upon the continuity of care and reduce patient satisfaction in medicine,44,45,46 although the social acceptability of dental therapists appears on balance to be positive.47,48,49 Unlike hygienists, the awareness of dental therapists as a professional group is not widespread.47 Despite this, it does appear that adults are willing to receive treatment under the NHS and there is evidence of increased patient satisfaction.48 However, some patients expect to pay less for treatment and are reticent about their use with young children or when anxious.47,49

To implement labour substitution, clinicians must be adequately trained and the availability and cost of appropriate training programmes are potential barriers.

Since the influential Nuffield Report into the Education and Training of Dental Auxiliaries was published in 1993 in the UK,50 the number of training places for dually-qualified hygiene-therapists across the UK has increased significantly.51 However, the supply of DCPs into the workforce market by the 17 schools in the United Kingdom is limited to approximately 300 a year and appears to reflect the low level of demand from general practice. In addition, many who graduate will either not be fully employed or will need to work in a large number of different practices to ensure full time employment.

Management of change is also a potential problem, as professionals seek to protect their clinical roles and maintain traditional boundaries.52 Managing a transition to labour substitution takes time and good human resource skills.53,54 As highlighted by Watt et al., the most important factors influencing change in dentistry include:55 potential financial risks associated with a new practice, progressive practice environment, supportive organisational structure, supportive professional networks and opportunity for training.

Need for services

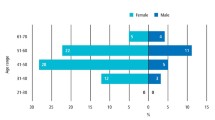

The other principal component in Birch's model is the need for services. This requires consideration of the changing epidemiology of the common diseases and population demographics, along with the need to carefully define the level of service required to deliver health. As highlighted by Figure 1, sequential Adult Dental Health Surveys have found that older cohorts experience greater dental needs.56 However, the consequence of this is uncertain, given the heterogeneity of the studies that have examined the survival rates for restorations57 and the limited evidence base for predicting future sequelae for heavily restored teeth. However, they may require remedial operative dentistry of increasing complexity, while the health of the remaining population steadily improves. Results from the latest survey suggest that the mean number of decayed or unsound teeth has now dropped to unity.

The role of labour substitution with respect to the ageing cohort is uncertain. It is possible that they will require increasingly advanced techniques that are potentially beyond a therapist's scope of practice, yet equally, they may require more periodontal management by hygienists and hygiene-therapists. As this group continue to age, there may be less demand as a result of increasing senility, yet an increasing need for prevention to reduce the risk of disease that becomes more common with age, like root caries. However, the potential for the greater use of DCPs for the remaining population would appear to remain important in order to deliver prevention.

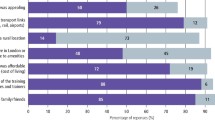

Determining the level of service required is a critical question. In the review of NHS dentistry, Steele argues that the NHS should prevent oral disease and the damage it causes, minimise the impact of oral disease when it occurs and maintain and restore patients' quality of life when this is affected.58 However, from the perspective of workforce planning, important questions remain about who the service should be delivered to and by whom. Evidence is also required to determine the efficacy of current provision. Approximately 95% of the costs for NHS dentistry are spent on routine care provided by GDPs, yet a large proportion of patients who regularly attend are asymptomatic and do not require treatment.59 Despite this, their care is delivered by the most expensive resource, the dentist. Although the principle of the NHS in the UK is that care should be available to all,60 approximately half of the population do not attend the dentist37 and this group tends to be those who are the most disadvantaged.59 If unchallenged this situation where those with lowest needs consume the majority of resources is likely to deteriorate further, given the evidence from the Adult Dental Health Surveys.

In addition, the definition of what constitutes need is important to determine. While health is defined as 'a state of complete physical, psychological, and social wellbeing and not simply the absence of disease or infirmity',61 there is an analytical difference between 'actual need', 'felt needs' described as 'wants' and expressed needs described as 'demands'.62 The latter two are predicated on good health literacy63 and so can be heavily influenced by patients' values and 'supplier induced demand'.64,65 Exchange theory describes the trade-off between the cost of an item and the value an individual places upon it.66,67 If patients do not value their need, they will be reluctant to seek out help or pay for it. In addition, given that dentistry is a business, there may be a vested interest in maintaining a 'fixed level' of demand to ensure profitability.64 A service that does not account for and address these issues, will not ameliorate the inverse care law.65

Finally, the impact of remuneration on dental services has received relatively little attention from a health economic perspective.68 These are heavily influenced by the prevailing political and professional culture69 and the type of remuneration system influences both the supply of services and the demands that patients place on GDPs.70 They are also important for the delivery of the productivity component of the Quality Innovation Productivity and Prevention agenda of the Department of Health.71

Per capita payments tend to secure effectiveness at the cost of patient-selection and under-treatment, while fee-for-item payments secure quality but often suffer from cost containment.69 Fixed salary remuneration removes the link between income and production, leading to high costs per patient.69 Financial incentives in any new contract within the NHS could have a significant impact on the use of skill mix. Equally the use of DCPs, rather than GDPs, has the potential to reduce the educational costs for service provision.

Future avenues for research

It is clear from the above that in addition to determining the efficacy of substituting GDPs for DCPs, there are a number of other important factors that need to be accounted for when exploring methods of employing skill mix to improve productivity (Table 1).

Rodriguez-Garcia proposed five criteria to evaluate the outcomes in health policy (Table 2).72 From a sociological perspective, practice and professional culture are key influences on behaviour, as are remuneration and incentives from an economic perspective.38,73,74 As highlighted above, few studies examining the cost-effectiveness of dental therapists in practice in the UK have been undertaken.75,76 Galloway et al.'s systematic review of DCP practice75 found that DCPs were as good as GDPs in their ability to screen, diagnose for disease and in their technical competence, while being marginally superior in oral health promotion. However, the quality of the 125 included studies was poor and many were dated. In the most recent literature review, Williams et al. concluded that there was 'an overwhelming need for well-designed interventions with robust evaluation to examine cost-effectiveness of skill mix'.76

It would also be an important aim of future research to explore the attitudes of GDPs towards employing skill mix across different remuneration systems. Equally, it would be important to determine the barriers that are perceived by GDPs to their use in existing contractual arrangements and explore the influence of both practice culture at a local level and professional culture at a broader national level, including the regulatory and legislative framework. This should include an examination of leadership styles, team management, referral processes and other sociological factors that have been outlined above.

However, the tension between the time taken to undertake research of the highest quality and the timescales that are required by policy makers, means that the prioritisation of these research needs is essential. In addition, there is a need for policy makers to ask the big questions, as ultimately, the productivity and the level of service delivered by the NHS are both bound to and influenced by such decisions at the highest level; what is the NHS prepared to pay for?

References

Birch S . Health human resource planning for the new millennium: inputs in the production of health, illness and recovery in populations. Can J Nurs Res 2002; 33: 109–114.

World Health Organisation. Everybody's business. Strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes. WHO's framework for action. Geneva: WHO, 2007.

Masnick K, McDonnell G . A model linking clinical workforce skill mix planning to health and health care dynamics. Hum Resour Health 2010; 8: 11.

Birch S, Kephart G, Tomblin-Murphy G, O'Brien-Pallas, Alder R, MacKenzie A . Human resources planning and the production of health: a needs-based analytical framework. Canadian Public Policy 2007; 23: S1–S16.

Gallagher J E, Patel R, Wilson N H F . The emerging dental workforce: long-term career expectations and influences. A quantitative study of final year dental students' views on their long-term career from one London Dental School. BMC Oral Health 2009; 9: 35.

Stewart F M J, Drummond J R, Carson L, Theaker E D . Senior dental students' career intentions, work-life balance and retirement plans. Br Dent J 2007; 203: 257–263.

Gallagher J E, Clarke W, Eaton K A, Wilson N H . Dentistry - a professional contained career in healthcare. A qualitative study of vocational dental practitioners' professional expectations. BMC Oral Health 2007; 16: 7–16.

Gallagher J E, Clarke W, Eaton K A, Wilson N H . A question of value: a qualitative study of vocational dental practitioners' views on oral healthcare systems and their future careers. Prim Dent Care 2009; 16: 29–37.

Davies L, Thomas D R, Sandham S J, Treasure E T, Chestnutt I G . Factors influencing the career aspirations and preferred modes of working in recent dental graduates in Wales. Prim Dental Care 2008; 15: 157–163.

Newton J T, Gibbons D E . The ethnicity of dental practitioners in the United Kingdom. Int Dent J 2001; 51: 49–51.

Bedi R, Gilthorpe M S . Ethnic and gender variations in university applicants to United Kingdom medical and dental schools. Br Dent J 2000; 189: 212–215.

Lightbody P, Nicholson S, Siann G, Walsh D . A respectable job: factors which influence young Asians' choice of career. Br J Guid Counsel 1997; 25: 67–79.

Harris R, Burnside G, Ashcroft A, Grieveson B . Job satisfaction of dental practitioners before and after a change in incentives and governance: a longitudinal study. Br Dent J 2009; 207: E4.

European Ministers of Education. The Bologna Declaration on the European space for higher education: an explanation. Bologna, European Union, 1999.

Gallagher J E, Wilson N H F . The future dental workforce? Br Dent J 2009; 206: 195–200.

Laurant M, Reeves D, Hermens R, Braspenning J, Grol R, Sibbald B . Substitution of doctors by nurses in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; (2): CD001271.

Ward P . The changing skill mix – experiences on the introduction of the dental therapist into general dental practice. Br Dent J 2006; 200: 193–197.

Meads G, Ashcroft J . The case for interprofessional collaboration. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2005. See also other publications of the UK Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE) at www.caipe.org.uk.

British Dental Association. Advice sheet D5. Working with dental therapists in general dental practice. London: BDA, 2007.

British Dental Association. Advice sheet D3. Employment of dental hygienists. London: BDA, 2007.

Sibbald B, Shen J, McBride A . Changing the skill-mix of the health care workforce. J Health Serv Res Policy 2004; 9(Suppl 1): 28–38.

Laurant M, Harmsen J, Wolersheims, Grol R, Faber M, Sibbald B . The impact of nonphysician clinicans: do they improve the quality and cost-effectiveness of health care services? Med Care Res Rev 2009; 66: 36S–89S.

Richardson M S C . Identifying, evaluating and implementing cost-effective skill mix. J Nurs Manag 1999; 7: 265–270.

Laurant M, Hermens R, Braspenning J, Grol R, Sibbald B . Nurse practitioners do not reduce the workload of GPs. Br Med J 2004; 328: 927–930.

Bower P, Sibbald B . The health care team. Chapter 1.3. In Jones R, Britten N, Culpepper L et al. (eds) Oxford textbook of primary medical care. Volume 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Gallagher J L, Wright D A . General dental practitioners' knowledge of and attitudes towards the employment of dental therapists in general practice. Br Dent J 2002; 193: 37–41.

Hay I S, Batchelor P A . The future role of dental therapists in the UK: a survey of District Dental Officers and General Practitioners in England and Wales. Br Dent J 1993; 175: 61–66.

Ireland R S . Dental therapists: their future role in the dental team. Dent Update 1997; 24: 269.

Ross M K, Ibbetson R J, Turner S . The acceptability of dually-qualified dental hygienist-therapists to general dental practitioners in South-East Scotland. Br Dent J 2007; 202: E8.

Douglass C W, Lipscomb J . Expanded function dental auxiliaries: potential for the supply of dental services in a national dental program. J Dent Educ 1979; 43: 556–567.

Ward P . The changing skill mix – experiences on the introduction of the dental therapist into general dental practice. Br Dent J 2006; 200: 193–197.

Newton J T, Gibbons D E . Vacant posts reported in dental practice: implications for human resource planning. Br Dent J 2002; 192: 37–39.

Harris R V, Haycox A . The role of team dentistry in improving access to dental care in the UK. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 353–356.

Holt R D, Murray J J . An evaluation of the role of New Cross auxiliaries and of their clinical contribution to the community dental services. Part 2 - Analysis of day books. Br Dent J 1980; 149: 259–263.

Jones D E, Gibbons D E, Doughty J F . The worth of a therapist. Br Dent J 1981; 151: 127–128.

Jones G, Evans C, Hunter L . A survey of the workload of dental therapists/hygienist-therapists employed in primary care settings. Br Dent J 2007; 204: E5.

House of Commons Health Select Committee. House of Commons Health Committee: Dental Services – Fifth Report of Session 2007–2008.

McDonald R, Cheraghi-Sohi S, Tickle M et al. The impact of incentives on the behaviour and performance of primary care professionals. SDO Project 08/1618/158. Available at: http://www.sdo.nihr.ac.uk/files/project/158-exec-summary.pdf. Accessed 11 November 2010.

Brocklehurst P R, Tickle M . Is skill mix profitable in the NHS dental contract? Br Dent J 2011; 210: 303–308.

Harris R, Burnside G . The role of dental therapists working in four PDS pilots: type of patients seen, work undertaken and cost-effectiveness within the context of the dental practice. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 491–496.

Godson J H, Williams S A, Csikar J I, Bradley S, Rowbotham J S . Dental therapy in the United Kingdom: part 2. A survey of reported working practices. Br Dent J 2009; 207: 417–423.

Adams A, Lugsden E, Chase J, Arber S, Bond S . Skill-mix changes and work intensification in nursing. Work, Employment and Society 2000; 14: 541–555.

Burke F J T, Wilson N H F, Christensen G J, Cheung S W, Brunton P A . Contemporary dental practice in the UK: demographic data and practising arrangements. Br Dent J 2005; 198: 39–43.

Baker R . Characteristics of practices, general practitioners and patients related to levels of patients' satisfaction with consultations. Br J Gen Pract 1996; 46: 601–605.

Wensing M, Vedsted P, Kersnik J et al. Patient satisfaction with availability of general practice: an international comparison. Int J Qual Health Care 2002; 14: 111–118.

Thomas L, Cullen N, McColl E, Rousseau N, Soutter J, Steen N . Guidelines in professions allied to medicine (Cochrane Review). In The Cochrane Library, Issue 3. Oxford: Update Software, 2002.

Dyer T A, Humphris G, Robinson P G . Public awareness and social acceptability of dental therapists. Br Dent J 2010; 208: E2.

Sun N, Burnside G, Harris R V . Patient satisfaction with care by dental therapists. Br Dent J 2010; 208: E9.

Dyer T A, Robinson P G . Exploring the social acceptability of skill-mix in dentistry. Int Dent J 2008; 58: 173–180.

The Nuffield Institute. The education and training of personnel auxiliary to dentistry. London: The Nuffield Institute, 1993.

Rowbotham J S, Godson J H, Williams S A, Csikar J I, Bradley S . Dental therapy in the United Kingdom: part 1. Developments in therapists' training and role. Br Dent J 2009; 207: 355–359.

Wilson A, Pearson D, Hassey A . Barriers to developing the nurse practitioner role in primary care – the GP perspective. Fam Pract 2002; 19: 641–646.

Doyal L, Cameron A . Reshaping the NHS workforce. Br Med J 2000; 320: 1023–1024.

Harris C, McBride A, Marchington M . Developing the concept of the 'Good' Employer in the NHS. Manchester: Health Organizations Research Centre, UMIST, 2002.

Watt R, McClone P, Evans D et al. The facilitating factors and barriers influencing change in dental practice in a sample of English general dental practitioners. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 485–489.

Office for National Statistics. Adult Dental Health Survey 1998. Available at http://www.statistics.gov.uk/pdfdir/dh0999.pdf (Accessed 14 April 2010).

Downer M C, Azli N A, Bedi R, Moles D R, Setchell D J . How long do routine dental restorations last? A systematic review. Br Dent J 1999; 187: 432–439.

Steele J . NHS dental services in England. London: Department of Health, 2009.

Milsom K M, Jones C, Kearney-Mitchell P, Tickle M . A comparative needs assessment of the dental health of adults attending dental access centres and general dental practices in Halton & St Helens and Warrington PCTs 2007. Br Dent J 2009; 206: 257–261.

Matlin A, Walmsley D . Some are more equal than others. Br Dent J 2010; 209: 261.

World Health Organization. Report of the working group on the concepts and principles of health promotion. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 1984.

Wright, J, Williams, R, Wilkinson J R . Health needs assessment - development and importance of health needs assessment. BMJ 1998; 316: 1310–1313.

Nutbeam D . Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st Century. Health Promotion International 2000; 15: 259–267.

Birch S . The identification of supplier-inducement in a fixed price system of health care provision: the case of dentistry in the United Kingdom. J Health Econ 1988; 7: 129–150.

Dixon A, Le Grand J . Is greater patient choice consistent with equity? The case of the English NHS. J Health Serv Res Policy 2006; 11: 162–166.

Kotler P, Armstrong G . Principles of marketing. London: Prentice Hall; 2005.

Bagozzi R P . Marketing as exchange: a theory of transactions in the marketplace. Am Behav Sci 1978; 21: 535–556.

Grytten J, Holst D, Skau I . Incentives and remuneration systems in dental services. Int J Health Care Finance Econ 2009; 9: 259–278.

Grytten J . Models for financing dental services. A review. Community Dent Health 2005; 22: 75–85.

Wright D, Batchelor P A . General dental practitioners' beliefs on the perceived effects of and their preferences for remuneration mechanisms. Br Dent J 2001; 192: 46–49.

Department of Health. The NHS Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention Challenge: an introduction for clinicians. London: Stationery Office, 2010.

Rodriguez-Garcia R . Health policy analysis in a nutshell. p 16. Washington, DC: The George Washington University Center for Global Health, 2000.

Watt R, McClone P, Evans D et al. The facilitating factors and barriers influencing change in dental practice in a sample of English general dental practitioners. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 485–489.

Gosden T, Forland F, Kristiansen I et al. Capitation, salary, fee-for-service and mixed systems of payment: effects on the behaviour of primary care physicians. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000; (3): CD002215.

Galloway J, Gorham J, Lambert M et al. The professionals complementary to dentistry: systematic review and synthesis. London: University College London, Eastman Dental Hospital, Dental Team Studies Unit, 2003.

Williams D M, Medina J, Wright D, Jones K, Gallagher J . A review of effective methods of delivery of care: skill-mix and service transfer to primary care settings. Prim Dent Care 2010; 17: 53–60.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brocklehurst, P., Tickle, M. The policy context for skill mix in the National Health Service in the United Kingdom. Br Dent J 211, 265–269 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.765

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.765

This article is cited by

-

Time to complete contemporary dental procedures – estimates from a cross-sectional survey of the dental team

BMC Oral Health (2023)

-

Shining a light on dental nurses and skill mix

BDJ Team (2023)

-

What are the possible barriers and benefits to the use of dental therapists within the UK Military Dental Service?

BDJ Team (2022)

-

What are the possible barriers and benefits to the use of dental therapists within the UK Military Dental Service?

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

Leadership in dentistry

British Dental Journal (2020)