Key Points

-

Older people in both hospital and the community are at risk from oro-dental problems.

-

Admission to hospital or a nursing home is an opportunity for both health promotion and screening for undetected pathology.

-

The responsibility of providing oral health care to patients in hospital and nursing homes lies with all health professionals involved in the patients' care.

-

The majority of those surveyed believed dentures to be 'free' to all pensioners on the NHS.

-

A high level of initial training for nurses and health care professionals regarding oral care for the elderly is required, otherwise the care of such elderly individuals might be sub-optimal.

Abstract

Objective The aim of this study was to compare the knowledge and views of nursing staff on both acute elderly care and rehabilitation wards regarding elderly persons' oral care with that of carers in nursing homes.

Subjects One hundred nurses working on acute, sub-acute and rehabilitation wards for elderly people (Group 1) and 75 carers in nursing homes (Group 2) were surveyed.

Design A semi-structured questionnaire.

Results Similar percentages of each group of nurses were registered with a dentist (86% and 88% respectively), although more hospital-based nurses were anxious about dental treatment compared with the nursing home group (40% and 28% respectively). More carers in nursing homes gave regular advice about oral care than the hospital-based nurses (54% and 43% respectively). Eighteen per cent of each group thought that edentulous individuals did not require regular oral care. Eighty-five per cent of hospital-based nurses and 95% of nursing home carers incorrectly thought that dentures were 'free' on the NHS. Although trends were observed between the two groups, no comparisons were statistically significant (Chi-square; level p < 0.05).

Conclusions Deficiencies exist in the knowledge of health care workers both in hospital and in the community setting, although the latter were less knowledgeable but more likely to give advice to older people.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Admission to hospital is not only a time for the active management of the presenting disease, but also an excellent opportunity for both health promotion and screening for undetected pathology. This also applies following admission to a nursing home. In addition, all elderly individuals should have exposure to appropriate education and care pertinent to oral health.

It has been shown that the oro-dental status of patients admitted to acute care of the elderly and rehabilitation wards is poor.1Many edentulous patients are lacking dentures and a large proportion of dentate elderly individuals require periodontal treatment, dental extractions and restorations.2 In a survey of long-term hospitalised elderly patients, Peltola et al.3 discovered that over three-quarters of patients were unable to eat normal food and following a clinical examination, almost half of the patients had their oral health ranked as poor. A study by Andersson et al.4 showed that oral health problems were common on admission to (86%), as well as at discharge from (51%), an elderly rehabilitation unit.

There is also a large oro-dental treatment burden in nursing homes. Studies have shown that between two-thirds and three-quarters of nursing home residents require assistance with oral hygiene measures.5,6 It has also been shown that over 70% of such individuals had not seen a dentist for over five years, and a third of patients have denture-related stomatitis.6 Other studies of institutionalised elderly patients have shown untreated dental caries levels in over 70%,7 and loose dentures and periodontal problems in almost half of the patients studied.8

Older people are less likely to complain about oral or dental conditions unless they are in pain and Wardh et al.9 found that elderly residents were generally not concerned about their oral health. Other barriers to providing oral care have been shown to be time constraints, difficulties with residents, lack of training of health care workers and poor understanding of the necessity for care.10,11

The responsibility of providing oral care to patients in hospital and nursing homes lies with all health professionals involved in the patients' care. Nurses and healthcare assistants are in a perfect position to provide the daily oral care of such patients. Wyche and Kerschbaum12 studied staff members working in hospices in the USA, where 100% of nurses and 88% of volunteers were providing oral care for clients. However, 87% of hospice programmes had no written oral healthcare protocol. In a further study by Hardy et al.,13 nursing aides reported providing preventive oral health services such as mouthrinsing (71%), toothbrushing (63%), and denture cleaning (37%). Patient compliance was reported as the major factor encouraging or discouraging these services.

In a survey of UK hospital patients unable to perform their own oral hygiene, over half were not asked if they required assistance with oral care. Eighty per cent with complete dentures and 60% of those with partial dentures did not have them cleaned at night. Of those with their own teeth and no dentures, 69% did not have their teeth cleaned at night. Nearly three-quarters of those surveyed rated the oral care given whilst in hospital as worse than that which they were able to provide at home.14

Education regarding oral healthcare is often provided during early training for nurses, and regular updates may not occur.15 In a Danish survey, only 17% of nurses felt they had received sufficient training in oral healthcare16 and in another study, the majority of nurses in a nursing home had received no oral care education.17 Separate studies in the USA and in the UK reported gaps in the knowledge of nursing staff in hospitals, but also reported a high level of interest in improving their ability to provide oral care services.18,19 Rak and Warren20 reported there to be a lack of specific dental knowledge in UK nursing staff and misconceptions over a broad range of topics were common, particularly in the recognition of oral cancer lesions21 which may have significant effects on patients' health. This reluctance may be due to oral care assistance being seen as more disagreeable than other nursing activities.22

In our previous study, we highlighted that nurses' knowledge of oral health issues is sometimes sub-optimal, and this may result in patients being given inappropriate advice regarding oral care.23 It was also highlighted that nurses' attitudes towards their own oral care may influence the advice that they give to patients. It was recommended that all staff who care for elderly patients in hospitals on a daily basis should have a core knowledge of oro-dental care. There is, however, a lack of studies comparing the oro-dental attitudes and knowledge of hospital nursing staff caring for elderly patients with the attitudes and knowledge of nursing home staff. In this study we intend to address this issue.

Materials and methods

One hundred and fifteen nurses and healthcare professionals working regularly on elderly care wards (Group 1) were contacted. The nurses were working in three areas: acute admission areas for care of the elderly, a sub-acute unit to which patients are either admitted with less severe illnesses or are transferred during a period of hospitalisation, and thirdly, designated rehabilitation wards. A further 75 carers working in nursing homes (Group 2) were contacted. The four nursing homes involved in the study were chosen because they were the most frequent nursing home discharge destination for elderly people leaving the hospital where the elderly care wards were based. The nursing home carers were either trained registered nurses or individuals who had completed an NVQ appropriate to their role as health care assistants. All staff in the nursing home who were surveyed had been working there at least three months. All carers who were asked to complete the questionnaire did so, resulting in a 100% response rate. Informed consent was sought to take part in the study; night staff were included if they formed part of the daytime rotations. Participation was on a voluntary basis and the anonymity of the respondents' data was assured.

The questionnaire was designed to determine the subjects' own oro-dental care practices and knowledge base regarding oral care of older people. Percentages for the subjects' responses were calculated. Statistical analysis for comparing the subgroups' responses was conducted using a Chi-square test (statistical significance at p < 0.05).

Results

There was an 87% response rate from the hospital staff, with 100 nurses and healthcare professionals completing the questionnaire, and a 100% response rate from the nursing home staff, with 75 participants completing the questionnaire. Of the hospital staff (Group 1), 58 were qualified nurses, 29 were healthcare assistants and the remaining 13 were a variety of 'agency' and student nurses. Forty-four were employed on a subacute ward; the remainder were divided between the rehabilitation unit (32) and acute wards (24). Of the nursing home staff (Group 2), 42% were qualified nurses and the remainder were health care workers.

The respondents were treated according to their designated group (Group 1 or 2) with no further differentiation between their qualifications and/or site of working. All were involved in the day-to-day oral care of elderly patients and their beliefs and opinions were therefore considered to be equally important.

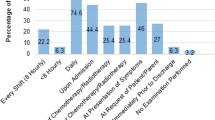

The main results are summarised in Table 1. The majority of the members of staff were registered with a dentist, although 14% of Group 1 and 12% of Group 2 were not. Forty per cent of those questioned in Group 1 reported to be anxious when attending a dentist, whilst only 28% of Group 2 reported a similar anxiety. The percentage of nurses reporting that they give oral care advice to the elderly in their care was similar, with 43% of Group 1 and 54% of Group 2 responding positively to this question.

When asked if it is important for edentulous individuals to attend a dentist regularly, 82% of each group thought it was important. Eighty-three per cent of Group 1 and 91% of Group 2 knew that a patient's dentures should be removed at night. The majority of staff believed that dentures were 'free' to all pensioners on the NHS, with 85% of Group 1 and 95% of Group 2 believing this to be so.

Although there are trends observed between the two groups, no differences were statistically significant (Chi-square; level p < 0.05).

Discussion

The results of this study broadly agree with other previous studies,18,21,22,23,24 in that deficiencies exist in healthcare professionals' knowledge of the appropriate oral care regimens for elderly people. These results further support the theory that deficiencies in knowledge may be associated with their own anxieties about dental attendance.23

Of the healthcare professionals who volunteered to take part in this study, a high proportion were registered with a dentist, with similar results for both groups (Group 1 86%; Group 2 88%). Dental anxiety was admitted by more hospital nurses compared to nursing home nurses (40% and 28% respectively), although this result was not statistically significant. Both these results are, however, lower than the level of dental anxiety in the general public.25

Disappointingly, only 43% of Group 1 nurses and 54% of Group 2 nurses gave oral care advice to the elderly patients in their care. This represents a missed opportunity for the delivery of oral care advice. Previous studies have highlighted a number of barriers to the delivery of oral care advice in these situations. These include time constraints, lack of knowledge and understanding, difficulties with patients, lack of training and disagreeable attitudes towards oral care activities.10,11,13,22

The importance of regular dental attendance is clear, as dental practitioners not only screen patients for dental decay and periodontal disease, but also for a plethora of oral soft tissue infections, tumours and other abnormalities.26 Hence, edentulous individuals should be examined by a dentist on a regular basis. This important point was not realised by 18% of respondents from both groups. The consequences of missing serious soft tissue pathology are obvious.

Although more people are retaining their natural teeth longer, there is still a significant proportion of people who wear dentures.25 The knowledge of denture care was generally good, although 17% of hospital nurses and 9% of nursing home nurses did not know that dentures should be removed at night. Although more nursing home nurses were correct in their views, this result was not statistically significant. This point is extremely important to prevent such conditions as denture stomatitis and acute pseudomembranous candidiasis (thrush). These conditions are both relatively common, with many denture wearers having some form of candidal infection.27,28

The vast majority of those surveyed (85% Group 1; 95% Group 2) believed dentures to be 'free' to all pensioners on the NHS. This is not the case unless the patient is also on income support. Although this result was not statistically significant, more nursing home nurses may believe dentures to be free to pensioners as patients in nursing homes are often seen by dentists from the Community Dental Service on domicillary visits. Treatment provided by the Community Dental Service, especially until recently, has generally been free of charge.

In conclusion, it appears that the attitudes and knowledge about dental matters in nursing staff caring for elderly patients is generally similar, whether the nurses are based in the hospital setting or in nursing homes. Although there were trends towards the Group 2 nurses being less anxious of dental attendance, more likely to provide oral care advice, and more knowledgeable about caring for edentulous patients, none of these results were statistically significant. It could be suggested that this might be because patients staying in nursing homes are often there for many years, and therefore the nursing staff may become more intimately involved with their oral care routines, although more rigid selection criteria for funding of nursing home places by social services makes this less likely.

It is clear from the literature search and results of this study that a higher level of initial training for nurses regarding oral care of the elderly is required.29,30,31,32 This should then be followed up by regular and contemporary updates. Indeed several pilot studies have been conducted with encouraging results. The Certificate in basic oral health promotion from the Royal Society of Health33 is a qualification that healthcare professionals should be encouraged to pursue. The opportunity for educating any healthcare professional in matters of oral health should not be lost, as significant improvements in lifestyle and general health can be achieved, especially in an elderly population.

Conclusion

There were deficiencies in the knowledge of health care workers in the hospital and community settings with respect to oro-dental care. These deficiencies might be related to the staff's own dental attitudes. Education of nurses, both in hospital and in the community, might improve not only their own oro-dental care, but also that of the patients under their care.

References

McNally L, Gosney M A, Field E A, Doherty U . The dental status of elderly in-patients. Age Aging 1998; 27: 47.

Steele J G, Walls A W G, Ayatollahi S M T, Murray J J . Major clinical findings from a dental survey of elderly people in three different English communities. Br Dent J 1996; 180: 17– 23.

Peltola P, Vehkalahti M M, Simoila R . Oral health related well being of the long-term hospitalised elderly. Gerodontology 2005; 22: 17– 23.

Andersson P, Hallberg I R, Renvert S . Comparison of oral health status on admission and at discharge in a group of geriatric rehabilitation patients. Oral Health Prev Dent 2003; 1: 221– 228.

Mersel A, Babayof I, Rosin A . Oral health needs of elderly short-term patients in a geriatric department of a general hospital. Spec Care Dentist 2000; 20: 72– 74.

Frenkel H, Harvey I, Newcombe R G . Oral health care among nursing home residents in Avon. Gerodontology 2000; 17: 33– 38.

Viglid M . Dental caries and the need for treatment among institutionalised elderly. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1989; 17: 102– 105.

Kiyak H A, Grayston M N, Crinean C L . Oral health problems and needs of nursing home residents. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1993; 21: 49– 52.

Wardh I, Berggren U, Andersson L, Sorenson S . Assessments of oral health care in dependent older persons in nursing facilities. Acta Odontol Scand 2002; 60: 330– 336.

Weeks J C, Fiske J . Oral care of people with disability: a qualitative exploration of the views of nursing staff. Gerodontology 1994; 11: 13– 17.

Chalmers J M, Levy S M, Buckwalter K C, Ettinger R L, Kambhu P P . Factors influencing nurses' aides' provision of oral care for nursing facility residents. Spec Care Dentist 1996; 16: 71– 79.

Wyche C J, Kerschbaum W E . Michigan hospice oral healthcare needs survey. J Dent Hyg 1994; 68: 35– 41.

Hardy D L, Darby M L, Leinbach R M, Welliver M R . Self-reporting of oral health services provided by nurses' aides in nursing homes. J Dent Hyg 1995; 69: 75– 82.

Longhurst R H . An evaluation of the oral care given to patients when staying in hospital. Prim Dent Care 1999; 6: 112– 115.

Longhurst R H . A cross-sectional study of the oral healthcare instruction given to nurses during their basic training. Br Dent J 1998; 184: 453– 457.

Viglid M . Knowledge, attitude and behaviour of institutional staff with regard to oral health in nursing homes. Tandlaegebladet 1989; 93: 53– 56.

Chung J P, Mojon P, Budtz-Jorgensen E . Dental care of elderly in nursing homes: perceptions of managers, nurses, and physicians. Spec Care Dentist 2000; 20: 12– 17.

Miller R, Rubinstein L . Oral health care for hospitalised patients: the nurse's role. J Nurs Educ 1987; 26: 362– 366.

Adams R . Qualified nurses lack adequate knowledge related to oral health, resulting in inadequate oral care of patients on medical wards. J Adv Nurs 1996; 24: 552– 556.

Rak O S, Warren K . An assessment of the level of dental and mouthcare knowledge amongst nurses working with elderly patients. Community Dent Health 1990; 7: 295– 301.

Logan H L, Ettinger R, McLeran H, Casko R . Common misconceptions about oral health in the older adult: nursing practices. Spec Care Dentist 1991; 11: 243– 247.

Wardh I, Andersson L, Sorensen S . Staff attitudes to oral health care. A comparative study of registered nurses, nursing home assistants and home care aides. Gerodontology 1997; 14: 28– 32.

Preston A J, Punekar S, Gosney M A . Oral care of elderly patients: nurses' knowledge and views. Postgrad Med J 2000; 76: 89– 91.

Wardh I, Hallberg L R, Berggren U, Andersson L, Sorensen S . Oral health care - a low priority in nursing. In-depth interviews with nursing staff. Scand J Caring Sci 2000; 14: 137– 142.

Nuttall N M et al. Adult dental health survey 1998. London: HMSO, 2001.

Field E A, Morrison T, Darling A E, Parr T A, Zakrzewska J M . Oral mucosal screening as an integral part of routine dental care. Br Dent J 1995; 179: 262– 266.

Marsh P D, Martin M V . Oral fungal infections. In Oral microbiology. 4th ed. pp 160. Oxford: Wright, 1999.

Preston A J, Gosney M A, Noon S, Martin M V . Oral flora of elderly patients following acute medical admission. Gerodontology 1999; 45: 49– 52.

Mynors-Wallis J, Davis D M . An assessment of the oral health knowledge and recall after a dental talk amongst nurses working with elderly patients: a pilot study. Gerodontology 2004; 21: 201– 204.

Paulsson G, Soderfeldt B, Fridlund B, Nederfors T . Recall of an oral health education programme by nursing personnel in special housing facilities for the elderly. Gerodontology 2001; 18: 7– 14.

Isaksson R, Paulsson G, Fridlund B, Nederfors T . Evaluation of an oral health education programme by nursing personnel in special housing facilities for the elderly. Part II: clinical aspects. Spec Care Dentist 2000; 20: 109– 113.

Pyle M A, Massie M, Nelson S . A pilot study on improving oral care in long-term care settings. Part II: procedures and outcomes. J Gerodontol Nurs 1998; 24: 35– 38.

Royal Society of Health. Certificate in basic oral health promotion: syllabus and regulations. London: RSH, 1997.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Preston, A., Kearns, A., Barber, M. et al. The knowledge of healthcare professionals regarding elderly persons' oral care. Br Dent J 201, 293–295 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4813973

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4813973

This article is cited by

-

Oral health ambassador scheme: training needs analysis in the community setting

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

Barriers and facilitators for provision of oral health care in dependent older people: a systematic review

Clinical Oral Investigations (2019)

-

Evidence summary: why is access to dental care for frail elderly people worse than for other groups?

British Dental Journal (2010)

-

Care home staff knowledge of oral care compared to best practice: a West of Scotland pilot study

British Dental Journal (2008)

-

A survey of denture identification marking within the United Kingdom

British Dental Journal (2007)