Abstract

We present a retrospective analysis on a cohort of low-grade, node-negative patients showing that human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status significantly affects the survival in this otherwise very good prognostic group. Our results provide support for the use of adjuvant trastuzumab in patients who are typically classified as having very good prognosis, not routinely offered standard chemotherapy, and who as such do not fit current UK prescribing guidelines for trastuzumab.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) amplification has become the prototype biomarker for translation of a laboratory discovery through to development of a highly successful individualised biological therapy agent. Slamon et al (1987) established HER2 as a poor prognostic marker for survival in breast cancer and developed a monoclonal antibody, trastuzumab, targeted to HER2, as a novel therapy for breast cancer patients. More recently, randomised trials in early breast cancer have shown the clinical benefit of trastuzumab after chemotherapy with significant overall survival benefit over chemotherapy alone (Romond et al, 2005; Slamon et al, 2006; Smith et al, 2007). As a result, trastuzumab has been introduced into routine clinical practice in the UK for HER2-positive patients who have completed their standard adjuvant treatment. Current Scottish and National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines parallel the herceptin adjuvant (HERA) trial entry criteria, according to which trastuzumab is offered only to those patients who have already received standard chemotherapy regimes as part of their treatment regime.

However, there remains a small subset of HER2-positive patients who are low grade and node negative and who are currently ineligible for trastuzumab treatment as clinically they have been deemed to have no requirement for standard adjuvant chemotherapy. In our region, approximately 25% of HER2 patients are not offered herceptin as they are deemed to be at ‘low risk’ (personal communication). Our study analyses a retrospective cohort of low-grade and node-negative tumours, traditionally classified by Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI) and Adjuvant! Online as ‘low risk’ to assess whether HER2 positivity affects survival in this otherwise very good prognostic group.

Methods

Patients

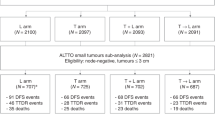

We have a large cohort (n=1351) of breast cancers diagnosed between 1980–2002 with full clinical follow-up (median 6.5 years) and pathological details taken from pathology reports. Tissue specimens from these cancers had been used to create tissue microarray technology (TMA) for research purposes (ethical approval was obtained). The grades of tumours from the cohorts diagnosed in the 1980–90s were reviewed for accuracy by a consultant pathologist (EAM). From this database, we wished to identify a group of patients who would classically be identified as ‘low risk’. We selected all node-negative, grade 1 or 2 cancers (n=362) for further analysis.

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 status assessment

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 status was identified using currently applicable clinical methodology (Bartlett et al, 2003). Dako Herceptest was used to quantify immunohistochemical staining. All 3+ (high-intensity) staining specimens were considered positive. All 2+ (moderate-intensity) staining specimens underwent FISH analysis and those who showed HER2 amplification were also classified as positive by the methods described earlier (Bartlett et al, 2003).

Analysis

SPSS (v15) was used to plot Kaplan–Meier survival curves using breast cancer-specific death as an outcome endpoint (log-rank testing). Cox regression analysis was carried out to evaluate the independence of HER2 in predicting the outcome in conjunction with age, oestrogen receptor (ER), grade, size and endocrine treatment. Cox regression hazard ratios were obtained for studying the effect of HER2 status on breast cancer-specific death in the subcategories split into ER status, age of the patient, and size of tumour.

Results

Patient characteristics

There were 362 node-negative, grade 1 or 2 cancers available for analysis. This group contained 90% ER-positive cases, with 71% having size <20 mm. In all, 80% of the patients were aged over 50 years, 10% received chemotherapy and 91% received endocrine therapy (tamoxifen). Table 1 shows the distribution of clinicopathological variables of the good prognostic group split by HER2 status. Fisher's exact test has been used to compare the variables between the HER2 positive and -negative groups. The HER2-positive patients were more likely to be grade 2, ER negative, and were more likely to have received chemotherapy.

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 status and survival

Sixty-one percent of cases were HER2 positive. In univariate log-rank testing, HER2-positive patients were significantly more likely to relapse on tamoxifen, giving 5-year breast cancer-specific survival rates of 68% compared with 96% for the HER2-negative group (P<0.001, Figure 1). This significance was retained in Cox regression analysis when analysed alongside grade, size, ER status, age and chemotherapy treatment (P<0.001). The overall hazard ratio for HER2 positivity was 5.65 (95% CI 2.4–13.1, P<0.001). This reduction in survival in HER2-positive cases persisted when patients were split into subgroups by ER status, tumour size and age (Table 2).

Discussion

Our results suggest that no HER2-positive patient should be classified as at ‘low risk’. We also suggest that our findings reinforce the importance of having HER2 results available on all patients at multidisciplinary meetings to enable clinicians to make informed decisions on outlook and treatment options.

There have been conflicting reports on the effect of HER2 status in good prognostic groups in the literature. Some have shown similar prognosis in node-negative patients (Paik et al, 1990a; Kallioniemi et al, 1991; Quenel et al, 1995; Press et al, 1997; Andrulis et al, 1998; Harbeck et al, 1999; Schmidt et al, 2005) even with small (1–10 mm) tumours (Joensuu et al, 2003) or ones with lower grade (Paik et al, 1990b). Other papers have not confirmed this (Richner et al, 1990; Rosen et al, 1995; Ko et al, 2007), although care must be undertaken when interpreting earlier studies, which may not have used the currently accepted methods of HER2 testing or are underpowered.

Two large studies, conducted recently, add substantial weight to our findings. In a study of over 2000 node-negative patients (Chia et al, 2008), HER2 status was shown to be an independent prognostic factor for disease-free survival in ER-negative patients. Rakkhit et al (2009) have shown HER2 to be a significant predictor of disease-free survival in a group of almost 1000 node-negative tumours <1 cm in size.

Our results are in keeping with those from the HERA trial, which suggested that patients with the best prognosis tumours (node negative and size 1–2 cm) had benefit from herceptin, similar to the overall cohort (Untch et al, 2008). The 29% of patients in the BCIRG 006 trial who were node negative (Slamon et al, 2006) also derived benefits similar to those derived by the whole cohort using trastuzamab, although they were included only if they had another high-risk feature (grade, ER negative over 2 cm).

The persistence of a reduction in survival in our HER2positive or ER-positive subgroup despite endocrine therapy is in keeping with the recent trans-ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) and BIG1–98 analysis based on HER2 status (Ranganathan et al, 2007) (Rasmussen et al, 2008) and suggests that we cannot rely solely on adjuvant endocrine therapy (tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitor) in these largely ER-positive patients.

Although this study suggests important findings with respect to HER2 status in good prognosis tumours, we accept the study's limitations with respect to the small number of HER2-positive patients in the cohort. Even within this restricted cohort, HER2-positive patients were less likely to be grade 1 and more likely to be ER negative. In addition, sub-analysis was not performed on tumours <10 mm in size because of the small number of tumours falling into the subgroup.

In conclusion, these results, in the context of other recently reported retrospective studies and adjuvant trials, provide support for the rationale of using adjuvant trastuzumab in this subgroup of patients, who are typically classified as having very good prognosis. These patients may not be routinely offered standard chemotherapy, and as such do not fit the current prescribing guidelines for trastuzumab. A clinical trial to assess the benefit of adjuvant trastuzumab within this group of HER2 patients would resolve this. Whether trastuzumab would be effective alone in these patients (without the potential side effects of standard chemotherapy regimes) deserves investigation. The combination of hormonal therapy and trastuzumab may be particularly beneficial in ER-positive patients, because trastuzumab may overcome the crosstalk between the HER and ER receptors, which is likely responsible for the reduced efficacy of hormonal therapy in this group.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Andrulis IL, Bull SB, Blackstein ME, Sutherland D, Mak C, Sidlofsky S, Pritzker KPH, Hartwick RW, Hanna W, Lickley L, Wilkinson R, Qizilbash A, Ambus U, Lipa M, Weizel H, Katz A, Baida M, Mariz S, Stoik G, Dacamara P, Strongitharm D, Geddie W, McCready D (1998) neu/erbB-2 amplification identifies a poor-prognosis group of women with node-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1340–1349

Bartlett J, Mallon E, Cooke T (2003) The clinical evaluation of HER-2 status: which test to use? J Pathol 199: 411–417

Chia S, Norris B, Speers C, Cheang M, Gilks B, Gown AM, Huntsman D, Olivotto IA, Nielsen TO, Gelmon K (2008) Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 overexpression as a prognostic factor in a large tissue microarray series of node-negative breast cancers. J Clin Oncol 26: 5697–5704

Harbeck N, Ross JS, Yurdseven S, Dettmar P, Polcher M, Kuhn W, Ulm K, Graeff H, Schmitt M (1999) HER-2/neu gene amplification by fluorescence in situ hybridization allows risk-group assessment in node-negative breast cancer. Int J Oncol 14: 663–671

Joensuu H, Isola J, Lundin M, Salminen T, Holli K, Kataja V, Pylkkanen L, Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T, Von Smitten K, Lundin J (2003) Amplification of erbB2 and erbB2 expression are superior to estrogen receptor status as risk factors for distant recurrence in pT1N0M0 breast cancer: a nationwide population-based study. Clin Cancer Res 9 (3): 923–930

Kallioniemi O-P, Holli K, Visakorpi T, Koivula T, Helin HH, Isola JJ (1991) Association of c-erbB-2 protein over-expression with high rate of cell proliferation, increased risk of visceral metastasis and poor long-term survival in breast cancer. Int J Cancer 49 (Suppl 5): 650–655

Ko S-S, Na Y-S, Yoon C-S, Park J-Y, Kim H-S, Hur M-H, Lee H-K, Chun Y-K, Kang S-S, Park B-W, Lee J-H (2007) The significance of c-erbB-2 overexpression and p53 expression in patients with axillary lymph node-negative breast cancer: a tissue microarray study. Int J Surg Pathol 15 (Suppl 2): 98–109

Paik S, Hazan R, Fisher ER, Sass RE, Fisher B, Redmond C, Schlessinger J, Lippman ME, King CR (1990a) Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project: prognostic significance of erbB-2 protein overexpression in primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 8: 103–112

Paik S, Hazan R, Fisher ER, Sass RE, Fisher B, Redmond C, Schlessinger J, Lippman ME, King CR (1990b) Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project: prognostic significance of erbB-2 protein overexpression in primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 8: 103–112

Press MF, Bernstein L, Thomas PA, Meisner LF, Zhou J-Y, Ma Y, Hung G, Robinson RA, Harris C, El Naggar A, Slamon DJ, Phillips RN, Ross JS, Wolman SR, Flom KJ (1997) HER-2/neu gene amplification characterized by fluorescence in situ hybridization: poor prognosis in node-negative breast carcinomas. J Clin Oncol 15 (Suppl 8): 2894–2904

Quenel N, Wafflart J, Bonichon F, de MI, Trojani M, Durand M, Avril A, Coindre J-M (1995) The prognostic value of c-erbB2 in primary breast carcinomas: a study on 942 cases. Breast Cancer Res Treat 35 (Suppl 3): 283–291

Rakkhit R, Broglio K, Peintinger F, Cardoso F, Hanrahan EO, Gonzalez-Angulo AM (2009) Significant increased recurrence rates among breast cancer patients with HER2-positive, T1a,bN0M0 tumors (abstract). Cancer Res 69 (Suppl): 701

Ranganathan A, Moore Z, O’Shaughnessy JA (2007) Retrospective quantitative analysis of the estrogen and progesterone receptors and analysis of HER2 status among patients with breast cancer in the arimidex, tamoxifen alone or in combination adjuvant phase III trial. Clin Breast Cancer 7 (Suppl 6): 451–454

Rasmussen BB, Regan MM, Lykkesfeldt AE, Dell’Orto P, Del Curto B, Henriksen KL, Mastropasqua MG, Price KN, Mery E, Lacroix-Triki M, Braye S, Altermatt HJ, Gelber RD, Castiglione-Gertsch M, Goldhirsch A, Gusterson BA, Thurlimann B, Coates AS, Viale G (2008) Adjuvant letrozole versus tamoxifen according to centrally-assessed ERBB2 status for postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive early breast cancer: supplementary results from the BIG 1-98 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 9 (Suppl 1): 23–28

Richner J, Gerber HA, Locher GW, Goldhirsch A, Gelber RD, Gullick WJ, Berger MS, Groner B, Hynes NE (1990) c-erbB-2 protein expression in node negative breast cancer. Annals Oncol 1 (Suppl 4): 263–268

Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J, Suman VJ, Geyer Jr CE, Davidson NE, Tan-Chiu E, Martino S, Paik S, Kaufman PA, Swain SM, Pisansky TM, Fehrenbacher L, Kutteh LA, Vogel VG, Visscher DW, Yothers G, Jenkins RB, Brown AM, Dakhil SR, Mamounas EP, Lingle WL, Klein PM, Ingle JN, Wolmark N (2005) Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 353: 1673–1684

Rosen PP, Lesser ML, Arroyo CD, Cranor M, Borgen P, Norton L (1995) Immunohistochemical detection of HER2/neu in patients with axillary lymph node negative breast carcinoma: A study of epidemiologic risk factors, histologic features, and prognosis. Cancer 75 (Suppl 6): 1320–1326

Schmidt M, Lewark B, Kohlschmidt N, Glawatz C, Steiner E, Tanner B, Pilch H, Weikel W, Kolbl H, Lehr HA (2005) Long-term prognostic significance of HER-2/neu in untreated node-negative breast cancer depends on the method of testing. Breast Cancer Res 7 (2): R256–R266

Slamon D, Eiermann W, Robert N, Pienkowski T, Martin M, Pawlicki M, Chan A, Smylie M, Liu M, Falkson C, Pinter T, Fornander T, Shiftan T, Valero V, Mackey J, Tabah-Fisch I, Buyse M, Lindsay M, Riva A, Bee V, Pegram M, Press M, Crown J (2006) BCIRG 006 2nd interim analysis phase III randomized trial comparing doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by docetaxel (AC-T) with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by docetaxel and trastuzumab (AC-TH) with docetaxel,carboplatin and trastuzumab (TCH) in HER2 positive early breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 100: 52

Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire WL (1987) Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science 235: 177–182

Smith I, Procter M, Gelber RD, Guillaume S, Feyereislova A, Dowsett M, Goldhirsch A, Untch M, Mariani G, Baselga J, Kaufmann M, Cameron D, Bell R, Bergh J, Coleman R, Wardley A, Harbeck N, Lopez RI, Mallmann P, Gelmon K, Wilcken N, Wist E, Sanchez RP, Piccart-Gebhart MJ (2007) 2-year follow-up of trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 369: 29–36

Untch M, Gelber RD, Jackisch C, Procter M, Baselga J, Bell R, Cameron D, Bari M, Smith I, Leyland-Jones B, de Azambuja E, Wermuth P, Khasanov R, Feng-Yi F, Constantin C, Mayordomo JI, Su C-H, Yu S-Y, Lluch A, Senkus-Konefka E, Price C, Haslbauer F, Sahui ST, Srimuninnimit V, Colleoni M, Coates AS, Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Goldhirsch A (2008) Estimating the magnitude of trastuzumab effects within patient subgroups in the HERA trial. Annals Oncol 19 (Suppl 6): 1090–1096

Acknowledgements

Unfortunately, during the preparation of this manuscript, our colleague and friend Professor Timothy Cooke passed away suddenly. We wish to acknowledge his support through the development and execution of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Tovey, S., Brown, S., Doughty, J. et al. Poor survival outcomes in HER2-positive breast cancer patients with low-grade, node-negative tumours. Br J Cancer 100, 680–683 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604940

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604940

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The dynamics of HER2-low expression during breast cancer progression

Breast Cancer Research and Treatment (2023)

-

Methods for Estimating Long-Term Outcomes for Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in HER2-Positive Unresectable or Metastatic Breast Cancer After Two or More Anti-HER2 Therapies

Targeted Oncology (2022)

-

Pertuzumab, trastuzumab and taxane-based treatment for visceral organ metastatic, trastuzumab-naïve breast cancer: real-life practice outcomes

Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology (2019)

-

Trastuzumab without chemotherapy in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer: subgroup results from a large observational study

BMC Cancer (2018)

-

Correlation of Gli1 and HER2 expression in gastric cancer: Identification of novel target

Scientific Reports (2018)