Abstract

Background:

Response to EGFR-targeted therapies in colorectal cancer patients has been convincingly associated with Kirsten-Ras (K-Ras) mutation status. Current mandatory mutation testing for patient selection is limited to the K-Ras ‘hotspot’ codons 12 and 13.

Methods:

Colorectal tumours (n=106) were screened for additional K-Ras mutations, phenotypes compared in transformation and Ras GTPase activating assays and gene and pathway changes induced by individual K-Ras mutants identified by microarray analysis. Taqman-based gene copy number and FISH analyses were used to investigate K-Ras gene amplification.

Results:

Four additional K-Ras mutations (Leu19Phe (1 out of 106 tumours), Lys117Asn (1 out of 106), Ala146Thr (7 out of 106) and Arg164Gln (1 out of 106)) were identified. Lys117Asn and Ala146Thr had phenotypes similar to the hotspot mutations, whereas Leu19Phe had an attenuated phenotype and the Arg164Gln mutation was phenotypically equivalent to wt K-Ras. We additionally identified a new K-Ras gene amplification event, present in approximately 2% of tumours.

Conclusions:

The identification of mutations outwith previously described hotspot codons increases the K-Ras mutation burden in colorectal tumours by one-third. Future mutation screening to facilitate optimal patient selection for treatment with EGFR-targeted therapies should therefore be extended to codon 146, and in addition should consider the unique molecular signatures associated with individual K-Ras mutations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Colorectal cancer accounts for approximately 15% of all cancers diagnosed annually in the United Kingdom, and is a major cause of death due to cancer, second only to lung and breast cancer (http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/incidence).

The majority of colorectal tumours arise from adenomatous polyps (adenomas), benign precursor lesions that develop from normal colonic mucosa. However, fewer than 10% of colorectal adenomas develop into invasive cancers and a number of molecular mechanisms including epigenetic events, DNA mismatch-repair defects, chromosomal rearrangements and mutations in key oncogenes and tumour suppressor genes have been suggested to regulate progression from adenoma to adenocarcinoma (de la Chapelle, 2004).

A genetic model for colorectal cancer highlighted key genes, including the tumour suppressor genes adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) and p53 and the oncogene Kirsten-Ras (K-Ras), the progressive acquisition of mutations in which was proposed to regulate the adenoma-carcinoma transition (Vogelstein et al, 1988). We subsequently refined this model (Smith et al, 2002), highlighting a significant increase in K-Ras mutation frequency in Dukes' C tumours, suggesting that K-Ras mutation status may be an important determinant of tumour progression. We additionally used comparative genomic hybridisation (CGH) analysis to identify common chromosomal aberrations in colorectal tumours, and highlighted an amplification of the region of chromosome 12p where the K-Ras gene is localised (Leslie et al, 2003). We and others have shown that K-Ras mutations are associated with significantly reduced survival in colorectal cancer patients (Andreyev et al, 2001; Conlin et al, 2005), although previous data is not entirely consistent (Etienne-Grimaldi et al, 2008; Winder et al, 2009). K-Ras mutation status has recently been convincingly associated with response to the new generation EGFR antagonists cetuximab (Erbitux) and panitumumab (Vectibix), where response is preferentially observed in wt K-Ras tumours (Lievre et al, 2006; Benvenuti et al, 2007; Khambata-Ford et al, 2007; Freeman et al, 2008; Karapetis et al, 2008; Ramos et al, 2008; Loupakis et al, 2009; Van Cutsem et al, 2009). K-Ras mutation testing is therefore increasingly recommended to facilitate selection of the most appropriate patients for treatment with EGFR antagonists (McNeill, 2008; van Krieken and Tol, 2009).

K-Ras is a member of the highly homologous family of small p21Ras G proteins (H-Ras, N-Ras and K-Ras) which transduce signals across the plasma membrane, principally by activation of the RAS–RAF–MEK–ERK–MAPK signalling cascade (Figure 1; (Barbacid, 1990)). Ras genes are the most frequently mutated oncogenes in human cancer, where tumour-specific mutations lead to the permanent activation of Ras signalling cascades, influencing proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis (Bos, 1989). Previous analyses of K-Ras mutations in human tumours have consistently focussed on single-point mutations in codons 12, 13 and 61, where mutation has been shown to result in reduced Ras GAP GTPase activity, locking the protein in the active Ras-GTP conformation (Ellis and Clark, 2000), although additional mutations at codons 19, 22 and 146 have been described in single colorectal tumour case reports (Orita et al, 1991; Miyakura et al, 2002; Akagi et al, 2007).

The Ras cycle. Ras proteins are key components of signal transduction pathways leading from cell-surface receptors to the control of cell proliferation, differentiation or death. Active Ras, where tumour-specific mutations lock Ras in the GTP-bound conformation, stimulates the RAS–RAF–MEK–ERK–MAP kinase signalling pathway.

Ras proteins regulate signal transduction by activating a number of downstream effector proteins, including the cytoplasmic serine/threonine protein kinase B-Raf (Figure 1). B-Raf mutations have also been identified in human cancers, including melanoma and thyroid, ovarian and colorectal tumours, although mutation frequency estimates in colorectal tumours vary from 1 to 20%, and have been particularly associated with tumours deficient in mismatch-repair activity (Wellbrock et al, 2004). The most common B-Raf mutation is a T to A transversion, resulting in a valine to glutamic acid substitution (V600E), present in approximately 90% of B-Raf mutant tumours (Davies et al, 2002), which results in a 500-fold increase in in vitro kinase activity and the induction of cell proliferation and transformation (Wan et al, 2004). Although K-Ras and B-Raf mutations are found in the same tumour types, they are thought to be mutually exclusive (Wellbrock et al, 2004), providing distinct but related mechanisms for the activation of K-Ras signalling pathways. B-Raf mutation status has also recently been associated with response to cetuximab and panitumumab where, like K-Ras, clinical response is limited to wt B-Raf tumours (Di Nicolantonio et al, 2008).

As K-Ras mutations in colorectal tumours are clearly important biomarkers of tumour progression and patient survival and also influence response to new generation EGFR antagonists, we have used a variety of experimental approaches to further investigate inter-individual differences in K-Ras mutation burden.

Materials and methods

Study participants

Patients (age range 45–80 years, median age 67 years, 64 males and 42 females) undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer at Ninewells Hospital, Dundee or Perth Royal Infirmary were invited to participate in the study. All patients were Caucasian, had pre-operative pathological confirmation of diagnosis (ICD-9 classification 153.0–153.9, 154.0–154.1) and had no history of previous cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, ulcerative colitis or diverticular disease. Patient details have been described previously (Smith et al, 2002). The study was approved by the Tayside Committee on Medical Research Ethics and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

DNA preparation

Primary colorectal tumour resection specimens were brought fresh from theatre to pathology and tumours selected by an experienced pathologist and stored in liquid nitrogen before analysis. Genomic DNA for mutation analysis was extracted using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Southampton, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All study participants provided a 10 ml venous blood sample, which was stored in EDTA blood containers at −20°C. Genomic DNA was extracted from 200 μl of whole blood, using a QIAamp 96 spin blood kit (Qiagen, Crawley, West Sussex, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

K-Ras and B-Raf mutation detection

Methods for K-Ras and B-Raf mutation detection and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of mutation frequencies are given in Appendix A.

Cell culture and transfection

The mouse embryonic fibroblast cell line NIH3T3 was obtained from Cancer Research UK cell services. NIH3T3 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% calf serum unless otherwise stated, at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Mammalian expression plasmids

The pEF.6 plink and pEFHA wt K-Ras plasmids were kind gifts from Professor Richard Marais (Institute of Cancer Research, London, UK). Site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) was carried out on the pEFHA wt K-Ras plasmid using the QuikChange II SDM kit (Agilent, South Queensferry, Edinburgh, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions to generate the following K-Ras mutations: G12V, G12D, G13D, Q61H, L19F, K117N, A146T and R164Q, using the oligonucleotide primers described in Table 1.

K-Ras foci formation assays

NIH3T3 cells were seeded at 2.5 × 105 cells in 35 mm culture dishes and allowed to adhere overnight before transfection with 250 ng of either pEF.6, pEFHA (wt K-Ras) or plasmids containing one of the following K-Ras mutants: G12V, G12D, G13D, Q61H, L19F, K117N, A146T or R164Q. After 24 h, cells were trypsinised and split (1 : 3) between two 10 cm3 plates and grown in DMEM containing 5% calf serum for 21 days, then fixed with methanol and stained with 0.5% (w/v) crystal violet. Foci greater then 5 mm were counted manually. All transfections were repeated three times and average foci counts and standard deviations calculated.

Ras GTPase activating assays

Ras activity was determined using a Ras activation assay kit (Millipore, Watford, Hertfordshire, UK). Briefly, cells were harvested 48 h after transfection in an Mg-containing lysis buffer (MLB). 500 μg of cell lysate from each sample was incubated with 10 μg of Raf-1 RBD agarose at 4°C for 30 min with gentle rocking. After washing three times with MLB, the agarose beads were re-suspended in 40 μl of NuPage LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen), and 20 μl of each sample separated on SDS-PAGE. A total of 30 μg of whole-cell lysate was additionally separated by SDS–PAGE for the analysis of total K-Ras expression.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed 48 h after transfection with MKK lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM sodium β-glycerophosphate, 5 mM sodium fluoride and protease inhibitors). Cell lysates were centrifuged at 13 000 r.p.m. for 15 min at 4°C and the soluble fraction transferred to a fresh 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube. Protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire, UK). For western blot analysis, 30 μg of each cell lysate was separated using the NuPage electrophoresis system (12% pre-cast polyacrylamide gels, Invitrogen) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Whatman, Maidstone, Kent, UK). Membranes were probed with anti-K-Ras (Merck, Nottingham, UK) and anti-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany) antibodies overnight at 4°C. Secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies (anti-mouse, Dako or anti-goat, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were applied for 1 h at room temperature before developing the membranes using enhanced chemiluminescence.

RNA transcription profiling analysis

NIH3T3 cells were plated at 2.5 × 105 cells per well in a 6-well plate and, following overnight attachment, transfected with 250 ng of pEF, wt K-Ras or one of the K-Ras mutants: G12V, G12D, G12C, G13D, Q61H, L19F, K117N, A146T and R164Q. After 48 h, cells were harvested in 1 ml of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and total RNA extracted according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was further purified using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen), eluted in a final volume of 50 μl RNAse-free dH20 and RNA quality and concentration assessed with a Bioanalyzer 2100 using the RNA 6000 Nano LabChip Kit (Agilent). RNA labelling and microarray hybridisation was carried out in collaboration with CXR Biosciences, Dundee, UK. Briefly 1 μg of total RNA sample was amplified to generate complementary RNA (cRNA) and labelled with cyanine 3-CTP (Cys3) using the QuickAmp labelling kit, one-colour (Agilent). Labelled cRNA was hybridised to Agilent 4 × 44K Whole Mouse Genome Oligo Microarray slides, which were scanned on an Agilent Microarray Scanner and images processed using Agilent Feature Extraction Software v9.1.

Microarray data was analysed using the open-source software Bioconducter 2.2. Lists of differentially expressed genes were generated comparing each of the K-Ras mutants with empty vector control using probes that exhibited an adjusted p value (false discovery rate (FDR)) ⩾0.05. Hierarchical clustering analysis was carried out using ‘Cluster’ (open source clustering software) and clusters visualised using Java TreeView.

K-Ras gene copy number assay

A new Taqman gene expression assay to evaluate K-Ras gene copy number was designed, in which K-Ras copy number was compared with the endogenous control gene RNAse P (copy number 2). K-Ras was amplified from genomic DNA extracted from normal and tumour tissues (n=96 normal/tumour pairs) from our colorectal patient series (Smith et al, 2002) with the oligonucleotide primers 5′-TTTAATACTTTTTATGTATTTCAGGGTGTTG-3′ (300 nM) and 5′-TTACCATCTTTGCTCATCTTTTCTTTAT-3′ (300 nM) and Taqman probe 5′-FAM-TGATGCCTTCTATACATTAGTTCGAGAAATTCGAAAA-TAMRA-3′ (100 nM), and expression compared with RNAse P by the comparative Ct method, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK).

Fluorescent in-situ hybridisation (FISH) analysis

Sections (4 μ M) of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumour tissue were provided by Tayside Tissue Bank on positively charged slides, which had been baked overnight at 56°C. Sections were deparaffinised using an automated protocol on a Vysis VP2000 processor, placed into a coplin-containing pre-warmed pre-treatment solution (Vysis, Maidenhead, Kent, UK) and incubated at 80°C for 30 min. Slides were then washed at room temperature in water for 1 min, before two 5 min washes in 2 × SSC before digestion with protease buffer at 37°C for 65 min. Following digestion, slides were washed three times in 2 × SSC for 2 min, before sequential washes in 70, 85 and 100% ethanol for 2 min each at room temperature and dried on a 37°C block. Meanwhile, 1 μl chromosome 12p BAC RP11-707G18 (Red) (BlueGnome), 1 μl chromosome 12q BAC RP11-89H19 (Green) (BlueGnome) and 9 μl LSI–WCP hybridisation buffer (Vysis) was mixed together for each slide and pipetted onto a 22 × 22 mm coverslip which was placed onto a region of the slide containing tumour tissue and placed onto a heat block at 75°C for 5 min to co-denature the probes and tumour tissue. Rubber cement was then applied to seal the coverslips and slides placed into a humidified hybridisation chamber in a 37°C incubator overnight. The next morning, coverslips were removed and slides placed into 0.4 × SSC at 72°C for 90 s and transferred to 2 × SSC containing 0.005% Tween for 30 s before being left to dry in the dark. In all, 20 μl of DAPI stain was then applied to coverslips, which were then gently applied to each slide and, after removing air bubbles, sealed with clear nail varnish. Slides were analysed on an epifluorescence microscope (Olympus BX60), where probe signals from 20 different cells in three different regions of the tumour tissue were counted and the average number of probe signals and s.d. calculated.

Results

Identification of new K-Ras mutations

We have previously described K-Ras mutations at codons 12, 13 and 61 in a series of 106 unselected colorectal tumours (Smith et al, 2002). Our K-Ras mutation analysis was performed by direct sequencing of K-Ras exon 1 (codons 12 and 13) and exon 2 (codon 61), and would therefore have detected any additional mutations in these exons. Codon 12 mutations were detected in 23 tumours (21.7%) and codon 13 mutations in 6 tumours (5.7%), whereas no codon 61 mutations were detected. Mutations at codon 19 (G57T, Leu19Phe) and in B-Raf (V600E) were found in single tumours (Table 2).

To identify additional K-Ras mutations, and to establish the relative frequencies of individual K-Ras mutations in human colorectal tumours, we used WAVE analysis followed by direct sequencing to screen the same tumour series for mutations in K-Ras exon 3 and exon 4B, the most common exon 4 splice variant. Four additional sequence changes were identified – an A to C change (Lys to Asn substitution) at codon 117, a G to A change (Ala to Thr substitution) at codon 146, a G to A change (Arg to Gln substitution) at codon 164 and a ‘silent’ C to T nucleotide substitution, which did not alter the aspartic acid residue at codon 173 (Table 2). Together, these K-Ras mutations and the B-Raf V600E mutation increase overall Ras pathway mutation frequency from 27.4 to 37.8%. The predicted localisation of each mutation in the functional domains of the K-Ras protein is illustrated in Figure 2.

Location of novel and hotspot Kirsten-Ras (K-Ras) mutations. The location of new (red) and hotspot (blue) K-Ras mutations are illustrated on a representation of the K-Ras protein sequence, together with the position of the novel K-Ras single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) (black). Putative GTP and effector binding sites and GAP and GEF interaction domains are highlighted.

To determine whether our reported sequence changes represented tumour-specific mutations or single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), genomic DNA from blood and tumour tissue was compared. Sequence changes at codons 19, 117, 146 and 164 were only detected in tumour DNA, whereas the codon 173 sequence change was detected in both blood and tumour DNA, and therefore represented a SNP (Table 2).

To determine the frequencies of the codon 117, 146 and 164 K-Ras mutations and the codon 173 SNP, PCR–RFLP assays were designed to permit rapid screening of blood and tumour DNA (Appendix A). Like the codon 19 mutation, the codon 117 and codon 164 mutations were found in single tumours, whereas the codon 146 mutation was found in 7 out of 106 (6.5%) of tumours. No tumours with codon 19, 117, 146 or 146 mutations had additional K-Ras mutations in codons 12, 13 or 61. The codon 173 SNP was found in 39 individuals, predicting an allele frequency of 18.2%. As this SNP did not lead to an amino acid substitution in the K-Ras protein, it was not analysed further.

Comparison of phenotypes associated with hotspot and new K-Ras mutations

Focus formation assays

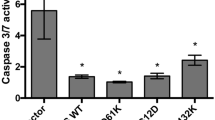

Phenotypes associated with the various K-Ras mutations have previously not been systematically evaluated. To compare the transformation potential of the K-Ras mutants, therefore, NIH3T3 cells were transiently transfected with plasmids expressing wt K-Ras and the K-Ras mutations G12V, G12D, G13D, Q61H, L19F, K117N, A146T and R164Q. Equivalence of plasmid loading was assessed spectrophotometrically and by western blotting for K-Ras (data not shown). Cells were stained with crystal violet and foci counted 21 days after transfection, as described in Materials and Methods (Figure 3). No foci were observed in untransfected cells or in cells transfected with wt K-Ras, whereas abundant foci were seen with each hotspot K-Ras mutation (Figure 3A). Codon 12 mutations had slightly greater transforming potential than codon 13 mutations and consistently greater transforming potential than the codon 61 Q61H mutation (Figure 3C). After transfection of additional K-Ras mutations, significant focus formation was observed for codon 117 and 146 mutations (Figure 3B). In contrast, the codon 164 mutation was phenotypically equivalent to wt K-ras with no evidence of foci formation and the codon 19 mutation generated low but consistent numbers of isolated foci (Figure 3C).

Focus formation assays. NIH3T3 cells were transfected with pEF.6 or plasmids containing wt or mutant K-Ras and foci visualised after crystal violet staining. (A) Cells transfected with empty vector or wt K-Ras were compared with previously described hotspot mutations. (B) The transforming potential of L19F, K117N, A146T and R164Q mutations were compared with the hotspot mutation G12V and wt K-Ras. All experiments were performed in duplicate and each set of transfections was repeated three times. (C) The combined results of all transfections, wherein total foci counts are presented ± SD are illustrated.

Ras activating assays

To assess which K-Ras mutations were in the active GTP-bound conformation, a Raf-1 binding assay was carried out as described in Materials and Methods. Raf-1 selectively binds GTP-bound Ras (rather than the inactive GDP-bound form) which, following immunoprecipitation, can be visualised by western blotting. Figure 4 illustrates the results of our analysis where, consistent with our focus formation experiments, the K-Ras G12V and L19F, K117N and A146T mutations are clearly in the active GTP-bound conformation. In contrast, the R164Q mutation, like wt K-Ras, was not GTP-bound.

Ras GTPase activating assays. Ras GTPase activating assays were carried out for each of the novel Kirsten-Ras (K-Ras) mutations and western blotting used to assess the expression of (A) active GTP-bound K-Ras (B) total K-Ras and (C) β-actin (loading control). The K-Ras G12V construct was included as a positive control for K-Ras protein in the active GTP-bound conformation.

RNA transcription-profiling experiments

To further compare and contrast the phenotypes associated with each of the K-Ras mutants, transcription-profiling experiments were carried out as described in Materials and Methods. Hierarchical clustering analysis revealed the presence of two major gene clusters, ‘cluster 1’ containing the G12V, G12C and G12D mutants and ‘cluster 2’ containing G13D, A146T, K117N, R164Q and L19F (Figure 5). It is interesting to note that the codon 12 mutants were most similar to wt K-Ras, whereas the K117N and A146T mutants clustered with the activating codon 13 and codon 61 hotspot mutants. The L19F and R164Q mutants formed a subcluster within cluster 2 suggesting, consistent with our foci formation data, that these mutants are phenotypically distinct from the G13D, A146T and K117N mutants. The presence of L19F in cluster 2 is consistent with our Ras GTPase assay data whereas, in contrast, our experimental data for R164Q predicted a ‘wt’ Ras phenotype. The presence of R164Q in cluster 2, rather than in cluster 1 with wt K-Ras was therefore initially surprising, but suggests that the R164Q mutation also has an ‘activating’ phenotype, albeit attenuated relative to the other mutations studied.

Hierarchical clustering analysis. RNA transcription profiling analysis was carried out as described in Materials and Methods. Lists of differentially expressed genes were generated comparing each of the Kirsten-Ras (K-Ras) mutants with empty vector control using probes that exhibited an adjusted P-value (false discovery rate (FDR)) ⩾0.05. Following hierarchical clustering analysis, gene clusters were represented on a heat map, where upregulated genes are highlighted in green and downregulated genes highlighted in red.

To further investigate the phenotypes associated with each of the K-Ras mutants, the expression of a diverse selection of genes associated a variety of cellular processes including signal transduction, cytoskeleton remodelling and cell adhesion was compared. Although further analysis of this complex dataset, including composite analysis of biological pathways and processes is ongoing and will be discussed in more detail in a future manuscript, representative examples of genes showing differential expression following the introduction of each K-Ras mutant are summarised in Table 3.

Consistent with our hierarchical clustering analysis, introduction of the R164Q mutation led to relatively few changes in gene expression or showed reduced pathway activation compared with the other mutants studied. However, there were examples of genes that were induced by all of the mutants studied, including the protein tyrosine phosphatase Ptpre and the Rho GTPase activating protein Arhgap6, and multiple examples of genes induced or repressed by all of the mutants with the exception of R164Q. These included the MAPK phosphatases DUSP4 and DUSP6, Ereg, Hbegf and Btc, all involved in EGFR binding, the Rho guanine-exchange factor NGEF, cell adhesion molecule Ceacam 1 and plasminogen activator inhibitor Serpinb2. Consistently, the novel A146T and K117N mutants (and, to a lesser extent, the L19F mutant) clustered with and influenced gene expression similarly to the previously described activating G13D and Q61H ‘hotspot’ mutations.

Of particular interest were genes, for example, Vegfa, Pak3, Pim1 and EII2 which were differentially expressed by cluster 1 but not cluster 2 mutants, genes, for example, Spry4, Igf1R, Creb1 and Tcf4 which were differentially expressed by cluster 2 mutants, and additional genes, for example, Jun, E2F2, Mmp3 and Glut-1 which were differentially regulated by each mutant studied.

K-Ras gene amplification

To investigate whether altered K-Ras activity could additionally result from gene amplification, a K-Ras gene copy number assay was designed and carried out as described in Materials and Methods and K-Ras copy number compared in normal and tumour tissues. In total, 2 of the 96 tumour pairs analysed (2.1%) showed tumour-specific copy number increases (Figure 6), one (study code 1264, wt K-Ras) with 4 tumour copies of K-Ras and the other (study code 1233, wt K-Ras) with 27 copies of the K-Ras gene. Assay reproducibility and linearity was demonstrated from the analysis of standard curves generated by serial dilutions of a wide concentration range of input genomic DNA (data not shown).

Kirsten-Ras (K-Ras) gene copy number assay. A novel K-Ras gene copy number assay was designed as described in Materials and Methods and used to screen genomic DNA samples extracted from 96 paired normal (N) and colorectal tumour (T) tissues. Representative results from six normal/tumour pairs are illustrated, highlighting increased copy number in samples 1233 and 1264.

K-Ras gene amplification was confirmed by FISH analysis as described in Materials and Methods (Figure 7). Figures 7A and B illustrate chromosome metaphase spreads confirming FISH probe specificities for chromosomes 12p and 12q, respectively, whereas Figures 7C and D show representative colorectal tumour FISH analysis. Figure 7C illustrates a tumour sample (study code 1271) in which the K-Ras gene is not amplified (red fluorescence=green fluorescence), whereas Figure 7D illustrates a colorectal tumour (study code 1264) with K-Ras gene amplification (red fluorescence>green fluorescence). Signals from the red 12p12.1 probe in tumour 1264 appear as a cluster of bright dots forming a line which is suggestive of a homogeneously staining region (HSR), a chromosomal region which is amplified either on the original chromosome or on another chromosome, as opposed to double minutes where the amplified gene is located in extra-chromosomal circular DNA molecules.

FISH analysis. Chromosome metaphase spreads were hybridised with FISH probes for (A) chromosome 12p (red) and (B) chromosome 12q (green) to confirm probe specificity and FISH analysis performed as described in Materials and Methods. Representative colorectal tumour sections (C) without and (D) with a K-Ras gene amplification are illustrated.

Discussion

Recent clinical data has shown a compelling association between K-Ras and B-Raf mutation status and response to EGFR blockade by cetuximab and panitumumab in the treatment of metastatic colorectal tumours (Benvenuti et al, 2007; Khambata-Ford et al, 2007; Freeman et al, 2008; Karapetis et al, 2008; Ramos et al, 2008). K-Ras mutations in colorectal tumours have been extensively documented, where recent meta analysis of more than 3000 tumours estimates an average K-Ras mutation frequency of 34.8% (Andreyev et al, 2001). This and the majority of previous analyses were, however, limited to codons 12 and 13, whereas only a minority of studies have additionally analysed codon 61. Although additional K-Ras mutations have been reported outwith these ‘hotspot’ codons, to our knowledge, there has been no systematic analysis of K-Ras mutation frequency in human colorectal tumours. Our use of ‘WAVE’ denaturing HPLC (dHPLC) analysis (Kuklin et al, 1997) allowed us to carry out a rapid, systematic analysis of the entire K-Ras coding sequence to identify colorectal tumours with sequence changes, the nature which were subsequently confirmed by conventional dideoxy sequencing.

Our data clearly demonstrates that K-Ras mutations in human colorectal tumours are likely to be significantly underestimated if only hotspot codons are analysed. Indeed, current mutation screening tests based on the hotspot codons 12 and 13 are likely to result in the mis-classification of up to one-third of patients. Although mutations at codons 19, 117 and 164 are relatively rare events, our data suggests that each K-Ras mutation may differentially influence treatment response. We would therefore recommend the adoption of comprehensive K-Ras mutation profiling, or at least the routine inclusion of the codon 146 mutation, for patient selection for cetuximab and related therapies.

Current data from the COSMIC database, which summarises literature data and the ongoing Sanger cancer-genome project describes 29 K-Ras colorectal tumour mutations outwith codons 12, 13 and 61, and more than 11 800 mutations at these hotspot codons (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/genetics/CGP/), but does not describe associated phenotypes. Consistent with our own data, codon 146 was the most frequently mutated of the mutations described. K-Ras codon 146 mutations have been described in a human colorectal tumour cell line (Higashi et al, 1990), in mice with thymic lymphomas (Sloan et al, 1990) and in a single human colorectal tumour case report (Orita et al, 1991). In more detailed molecular profiling studies, codon 146 mutations were described in 4% of two independent colorectal tumour series from Hong Kong and the United States of America (Edkins et al, 2006) and in chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia (Gelsi-Boyer et al, 2008; Tyner et al, 2009). Consistent with our own data, Tyner et al (2009) reported an oncogenic phenotype associated with the K-Ras 146 mutation in leukaemia and Loupakis et al (2009) have recently reported that a patient with metastatic colorectal cancer with a K-Ras 146 mutation was resistant to cetuximab.

There is only a single report of K-Ras codon 19 mutations in human colorectal tumours (Akagi et al, 2007), in which in vitro elevation of active Ras-GTP levels, anchorage-independent growth and increased tumourigenicity in nude mice was demonstrated. A codon 19 mutation has additionally been described in H-Ras in a human pituitary carcinoma metastases (Pei et al, 1994). There are two recent reports of codon 117 mutations – the first in K-Ras in human colorectal tumours (Wojcik et al, 2008) and the second in H-Ras, associated with activation of the RAS–MAPK pathway and the mental retardation Costello syndrome (Denayer et al, 2008). It is interesting to note that Costello syndrome has been associated with increased cancer predisposition (Gripp, 2005). There are no reports of K-Ras 164 mutations, and mutations at this codon were not identified by Sanger cancer genome project investigators.

Recent clinical data convincingly associates response to anti-EGFR therapies with K-Ras mutation status in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer where, logically, response is preferentially observed in K-Ras wt tumours (Lievre et al, 2006; Benvenuti et al, 2007; Khambata-Ford et al, 2007; Freeman et al, 2008; Karapetis et al, 2008; Ramos et al, 2008; Loupakis et al, 2009; Van Cutsem et al, 2009) which retain the ability to respond to EGFR blockade. Our description of K-Ras gene amplification in a subset of wt tumours is of particular interest in this regard as increased K-Ras gene copy number may lead to a more active ‘mutation’-like phenotype. Experiments to investigate this possibility are currently underway in our laboratory.

It is interesting to note that our transcription profiling analysis revealed some similarities but many marked differences in gene expression following the introduction of the individual K-Ras mutants. We found that the codon 117 and the common codon 146 mutations cluster with the previously described activating mutations at codons 13 and 61, highlighting differences in individual mutation phenotypes. Our analysis of K-Ras induced gene expression identified a number of genes previously associated with K-Ras signalling, for example the MAPK dual specificity phosphatases DUSP4 and DUSP6. DUSPs are key regulators of the balance between kinase pathway activation and inactivation, and have previously been reported to be upregulated in an adaptive response, creating a negative feedback loop following MAPK pathway activation (Keyse, 2008). Consistent with our own data, DUSP4 expression has previously been shown to be increased in pancreatic tumours with K-Ras mutations (Yip-Schneider et al, 2001) and DUSP6 expression increased in a variety of tumour types with mutations in Ras or Raf pathway genes (Croonquist et al, 2003; Warmka et al, 2004; Bloethner et al, 2005). Of particular interest, however, was our observation that certain signalling cascades, including those mediated by Igf1 and Vegf, were differentially activated by cluster 1 and cluster 2 K-Ras mutants, suggesting that not only the presence but the specific molecular characteristics of individual K-Ras mutations may be important determinants of both tumour progression and treatment response. For example, recent data suggests that glucose deprivation can promote the acquisition of K-Ras mutations in human tumours and reports upregulation of the glucose transporter GLUT-1 in K-Ras mutant tumours (Yun et al, 2009). Our data confirms this hypothesis, but shows GLUT-1 induction restricted to the codon 12, 13, 61 and 117 mutations, with no change in GLUT-1 expression associated with the introduction of codon 19, 146 or 164 mutations, again reflecting phenotypic heterogeneity.

Current clinical data is sufficiently compelling that K-Ras mutation testing to facilitate the selection of patients most likely to benefit from anti-EGFR therapy is increasingly recommended in clinical practise (McNeill, 2008; van Krieken and Tol, 2009), and has resulted in a recent formal recommendation from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network that patients with K-Ras tumour mutations should not be treated with cetuximab or panitumumab (McNeill, 2008). There is increasing interest in the identification of prognostic molecular markers, which may be used to select the most appropriate patients for adjuvant chemotherapy or to identify colorectal cancer patients at increased risk of disease progression. Although the clinical implications of non-hotspot K-Ras mutations requires further validation both as prognostic markers and therapeutic targets, our data suggests that future analysis of K-Ras mutations and quantitation of mutation burden in colorectal tumours should not be limited to previously described mutation hotspots and should additionally consider the unique molecular signatures associated with individual K-Ras mutations.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Akagi K, Uchibori R, Yamaguchi K, Kurosawa K, Tanaka Y, Kozu T (2007) Characterization of a novel oncogenic K-ras mutation in colon cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 352: 728–732

Andreyev HJ, Norman AR, Cunningham D, Oates J, Dix BR, Iacopetta BJ, Young J, Walsh T, Ward R, Hawkins N, Beranek M, Jandik P, Benamouzig R, Jullian E, Laurent-Puig P, Olschwang S, Muller O, Hoffmann I, Rabes HM, Zietz C, Troungos C, Valavanis C, Yuen ST, Ho JW, Croke CT, O'Donoghue DP, Giaretti W, Rapallo A, Russo A, Bazan V, Tanaka M, Omura K, Azuma T, Ohkusa T, Fujimori T, Ono Y, Pauly M, Faber C, Glaesener R, de Goeij AF, Arends JW, Andersen SN, Lovig T, Breivik J, Gaudernack G, Clausen OP, De Angelis PD, Meling GI, Rognum TO, Smith R, Goh HS, Font A, Rosell R, Sun XF, Zhang H, Benhattar J, Losi L, Lee JQ, Wang ST, Clarke PA, Bell S, Quirke P, Bubb VJ, Piris J, Cruickshank NR, Morton D, Fox JC, Al-Mulla F, Lees N, Hall CN, Snary D, Wilkinson K, Dillon D, Costa J, Pricolo VE, Finkelstein SD, Thebo JS, Senagore AJ, Halter SA, Wadler S, Malik S, Krtolica K, Urosevic N (2001) Kirsten ras mutations in patients with colorectal cancer: the ‘RASCAL II’ study. Br J Cancer 85: 692–696

Barbacid M (1990) Ras oncogenes: their role in neoplasia. Eur J Clin Invest 20: 225–235

Benvenuti S, Sartore-Bianchi A, Di Nicolantonio F, Zanon C, Moroni M, Veronese S, Siena S, Bardelli A (2007) Oncogenic activation of the RAS/RAF signaling pathway impairs the response of metastatic colorectal cancers to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody therapies. Cancer Res 67: 2643–2648

Bloethner S, Chen B, Hemminki K, Muller-Berghaus J, Ugurel S, Schadendorf D, Kumar R (2005) Effect of common B-RAF and N-RAS mutations on global gene expression in melanoma cell lines. Carcinogenesis 26: 1224–1232

Bos JL (1989) ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res 49: 4682–4689

Conlin A, Smith G, Carey FA, Wolf CR, Steele RJ (2005) The prognostic significance of K-ras, p53, and APC mutations in colorectal carcinoma. Gut 54: 1283–1286

Croonquist PA, Linden MA, Zhao F, Van Ness BG (2003) Gene profiling of a myeloma cell line reveals similarities and unique signatures among IL-6 response, N-ras-activating mutations, and coculture with bone marrow stromal cells. Blood 102: 2581–2592

Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, Teague J, Woffendin H, Garnett MJ, Bottomley W, Davis N, Dicks E, Ewing R, Floyd Y, Gray K, Hall S, Hawes R, Hughes J, Kosmidou V, Menzies A, Mould C, Parker A, Stevens C, Watt S, Hooper S, Wilson R, Jayatilake H, Gusterson BA, Cooper C, Shipley J, Hargrave D, Pritchard-Jones K, Maitland N, Chenevix-Trench G, Riggins GJ, Bigner DD, Palmieri G, Cossu A, Flanagan A, Nicholson A, Ho JW, Leung SY, Yuen ST, Weber BL, Seigler HF, Darrow TL, Paterson H, Marais R, Marshall CJ, Wooster R, Stratton MR, Futreal PA (2002) Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 417: 949–954

de la Chapelle A (2004) Genetic predisposition to colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 4: 769–780

Denayer E, Parret A, Chmara M, Schubbert S, Vogels A, Devriendt K, Frijns JP, Rybin V, de Ravel TJ, Shannon K, Cools J, Scheffzek K, Legius E (2008) Mutation analysis in Costello syndrome: functional and structural characterization of the HRAS p.Lys117Arg mutation. Hum Mutat 29: 232–239

Di Nicolantonio F, Martini M, Molinari F, Sartore-Bianchi A, Arena S, Saletti P, De Dosso S, Mazzucchelli L, Frattini M, Siena S, Bardelli A (2008) Wild-type BRAF is required for response to panitumumab or cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 26: 5705–5712

Edkins S, O'Meara S, Parker A, Stevens C, Reis M, Jones S, Greenman C, Davies H, Dalgliesh G, Forbes S, Hunter C, Smith R, Stephens P, Goldstraw P, Nicholson A, Chan TL, Velculescu VE, Yuen ST, Leung SY, Stratton MR, Futreal PA (2006) Recurrent KRAS codon 146 mutations in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Biol Ther 5: 928–932

Ellis CA, Clark G (2000) The importance of being K-Ras. Cell Signal 12: 425–434

Etienne-Grimaldi MC, Formento JL, Francoual M, Francois E, Formento P, Renee N, Laurent-Puig P, Chazal M, Benchimol D, Delpero JR, Letoublon C, Pezet D, Seitz JF, Milano G (2008) K-Ras mutations and treatment outcome in colorectal cancer patients receiving exclusive fluoropyrimidine therapy. Clin Cancer Res 14: 4830–4835

Freeman DJ, Juan T, Reiner M, Hecht JR, Meropol NJ, Berlin J, Mitchell E, Sarosi I, Radinsky R, Amado RG (2008) Association of K-ras mutational status and clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer receiving panitumumab alone. Clin Colorectal Cancer 7: 184–190

Gelsi-Boyer V, Trouplin V, Adelaide J, Aceto N, Remy V, Pinson S, Houdayer C, Arnoulet C, Sainty D, Bentires-Alj M, Olschwang S, Vey N, Mozziconacci MJ, Birnbaum D, Chaffanet M (2008) Genome profiling of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: frequent alterations of RAS and RUNX1 genes. BMC Cancer 8: 299

Gripp KW (2005) Tumor predisposition in Costello syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 137C: 72–77

Higashi T, Sasai H, Suzuki F, Miyoshi J, Ohuchi T, Takai S, Mori T, Kakunaga T (1990) Hamster cell line suitable for transfection assay of transforming genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 2409–2413

Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ, O'Callaghan CJ, Tu D, Tebbutt NC, Simes RJ, Chalchal H, Shapiro JD, Robitaille S, Price TJ, Shepherd L, Au HJ, Langer C, Moore MJ, Zalcberg JR (2008) K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 359: 1757–1765

Keyse SM (2008) Dual-specificity MAP kinase phosphatases (MKPs) and cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev 27: 253–261

Khambata-Ford S, Garrett CR, Meropol NJ, Basik M, Harbison CT, Wu S, Wong TW, Huang X, Takimoto CH, Godwin AK, Tan BR, Krishnamurthi SS, Burris III HA, Poplin EA, Hidalgo M, Baselga J, Clark EA, Mauro DJ (2007) Expression of epiregulin and amphiregulin and K-ras mutation status predict disease control in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with cetuximab. J Clin Oncol 25: 3230–3237

Kuklin A, Munson K, Gjerde D, Haefele R, Taylor P (1997) Detection of single-nucleotide polymorphisms with the WAVE DNA fragment analysis system. Genet Test 1: 201–206

Leslie A, Pratt NR, Gillespie K, Sales M, Kernohan NM, Smith G, Wolf CR, Carey FA, Steele RJ (2003) Mutations of APC, K-ras, and p53 are associated with specific chromosomal aberrations in colorectal adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res 63: 4656–4661

Lievre A, Bachet JB, Le Corre D, Boige V, Landi B, Emile JF, Cote JF, Tomasic G, Penna C, Ducreux M, Rougier P, Penault-Llorca F, Laurent-Puig P (2006) KRAS mutation status is predictive of response to cetuximab therapy in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 66: 3992–3995

Loupakis F, Ruzzo A, Cremolini C, Vincenzi B, Salvatore L, Santini D, Masi G, Stasi I, Canestrari E, Rulli E, Floriani I, Bencardino K, Galluccio N, Catalano V, Tonini G, Magnani M, Fontanini G, Basolo F, Falcone A, Graziano F (2009) KRAS codon 61, 146 and BRAF mutations predict resistance to cetuximab plus irinotecan in KRAS codon 12 and 13 wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 101: 715–721

McNeill C (2008) K-Ras mutations are changingpractice in advanced colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 100: 1667–1669

Miyakura Y, Sugano K, Fukayama N, Konishi F, Nagai H (2002) Concurrent mutations of K-ras oncogene at codons 12 and 22 in colon cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 32: 219–221

Orita S, Higashi T, Kawasaki Y, Harada A, Igarashi H, Monden T, Morimoto H, Shimano T, Mori T, Miyoshi J (1991) A novel point mutation at codon 146 of the K-ras gene in a human colorectal cancer identified by the polymerase chain reaction. Virus Genes 5: 75–79

Pei L, Melmed S, Scheithauer B, Kovacs K, Prager D (1994) H-ras mutations in human pituitary carcinoma metastases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 78: 842–846

Ramos FJ, Macarulla T, Capdevila J, Elez E, Tabernero J (2008) Understanding the predictive role of K-ras for epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted therapies in colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 7 (Suppl 2): S52–S57

Sloan SR, Newcomb EW, Pellicer A (1990) Neutron radiation can activate K-ras via a point mutation in codon 146 and induces a different spectrum of ras mutations than does gamma radiation. Mol Cell Biol 10: 405–408

Smith G, Carey FA, Beattie J, Wilkie MJ, Lightfoot TJ, Coxhead J, Garner RC, Steele RJ, Wolf CR (2002) Mutations in APC, Kirsten-ras, and p53–alternative genetic pathways to colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 9433–9438

Tyner JW, Erickson H, Deininger MW, Willis SG, Eide CA, Levine RL, Heinrich MC, Gattermann N, Gilliland DG, Druker BJ, Loriaux MM (2009) High-throughput sequencing screen reveals novel, transforming RAS mutations in myeloid leukemia patients. Blood 113: 1749–1755

Van Cutsem E, Kohne CH, Hitre E, Zaluski J, Chang Chien CR, Makhson A, D'Haens G, Pinter T, Lim R, Bodoky G, Roh JK, Folprecht G, Ruff P, Stroh C, Tejpar S, Schlichting M, Nippgen J, Rougier P (2009) Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 360: 1408–1417

van Krieken H, Tol J (2009) Setting future standards for KRAS testing in colorectal cancer. Pharmacogenomics 10: 1–3

Vogelstein B, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, Kern SE, Preisinger AC, Leppert M, Nakamura Y, White R, Smits AM, Bos JL (1988) Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. N Engl J Med 319: 525–532

Wan PT, Garnett MJ, Roe SM, Lee S, Niculescu-Duvaz D, Good VM, Jones CM, Marshall CJ, Springer CJ, Barford D, Marais R (2004) Mechanism of activation of the RAF-ERK signaling pathway by oncogenic mutations of B-RAF. Cell 116: 855–867

Warmka JK, Mauro LJ, Wattenberg EV (2004) Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-3 is a tumor promoter target in initiated cells that express oncogenic Ras. J Biol Chem 279: 33085–33092

Wellbrock C, Karasarides M, Marais R (2004) The RAF proteins take centre stage. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 875–885

Winder T, Mundlein A, Rhomberg S, Dirschmid K, Hartmann BL, Knauer M, Drexel H, Wenzl E, De Vries A, Lang A (2009) Different types of K-Ras mutations are conversely associated with overall survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep 21: 1283–1287

Wojcik P, Kulig J, Okon K, Zazula M, Mozdzioch I, Niepsuj A, Stachura J (2008) KRAS mutation profile in colorectal carcinoma and novel mutation–internal tandem duplication in KRAS. Pol J Pathol 59: 93–96

Yip-Schneider MT, Lin A, Marshall MS (2001) Pancreatic tumor cells with mutant K-ras suppress ERK activity by MEK-dependent induction of MAP kinase phosphatase-2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 280: 992–997,

Yun J, Rago C, Cheong I, Pagliarini R, Angenendt P, Rajagopalan H, Schmidt K, Willson JK, Markowitz S, Zhou S, Diaz Jr LA, Velculescu VE, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N (2009) Glucose deprivation contributes to the development of KRAS pathway mutations in tumor cells. Science 325: 1555–1559

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Richard Marais; Professor of Molecular Oncology, Institute of Cancer Research for technical advice and the generous gift of protocols and K-Ras expression plasmids; Dr Simon Plummer, CXR Biosciences, Dundee, UK for carrying out the transcription profiling analysis; Probir Chakravarty, Cancer Research UK for helping with bioinformatics analysis; Dr Norman Pratt, Dundee, UK for helping with FISH analysis; and Tayside Tissue Bank for helping with patient recruitment and sample processing. We acknowledge financial support from Cancer Research UK (C4639/A5661), Food Standards Agency (Contract TO1004) and the Ninewells Cancer Campaign, and funding from the MRC and Cancer Research UK for Tayside Tissue Bank.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Kirsten-Ras (K-Ras) mutation detection and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of mutation frequencies

K-Ras Exon 3 and Exon 4 mutation detection

Mutations in exons 3 and 4 of the K-Ras gene were identified using the Transgenomic WAVE denaturing HPLC system. PCR products for WAVE analysis were generated using the Expand High Fidelity PCR system (Roche, Welingkar garden, UK) incorporating Taq polymerase with enhanced proofreading activity. A 200 bp PCR product encompassing K-Ras exon 3 was generated using the oligonucleotide primers 5′-TTCTTTCCCAGAGAACAAATTAA-3′ and 5′-AGATCTGTATTTATTTCAGTGTTACTTACC-3′. Similarly, a 261 bp PCR product encompassing K-Ras Exon 4b was generated using the oligonucleotide primers 5′-TACTTTTTATGTATTTCAGGGTGTTG-3′ and 5′-GCTAACAGTCTGCATGGAGC-3′.

Assay conditions (acetonitrile gradient and temperature profile) were optimised for WAVE analysis of each PCR fragment using Transgenomic WAVEMAKER 4.1 software, according to the manufacturer's instructions. K-Ras exon 3 was analysed at 55°C with an initial concentration of 51% Buffer B (0.1 M TEAA, 25% acetonitrile) and exon 4 at 55°C with an initial concentration of 54% Buffer B. All samples were denatured and cooled slowly to room temperature before WAVE analysis to maximise heteroduplex formation.

Direct sequencing

The K-Ras mutations detected by WAVE analysis were confirmed by direct sequencing of PCR products. This analysis was performed by the DNA analysis facility, Department of Molecular and Cellular Pathology, Ninewells Hospital and Medical School, Dundee DD1 9SY, UK, using 16 capillary ABI 3100 Genetic Analysers (Applied Biosystems). Before sequencing, all PCR products were purified using QIAquick PCR purification kits (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. All sequences obtained were aligned with previously published sequences (NCBI Genbank Accession Numbers L00047 and L00049 for K-Ras exons 3 and 4b, respectively); the presence and nature of each mutation was confirmed by repeat PCR and sequencing.

RFLP analysis of K-Ras codon 117 mutations

To permit rapid identification of the K-Ras codon 117 mutation, a PCR–RFLP assay was designed where the presence of the mutation created a recognition site for the restriction enzyme Bsr S1. A 288 bp PCR product was amplified using the primers 5′-GATCTTTTGAGAGAGATACAAGGTTTC-3′ and 5′-TGTTCTAGAAGGCAAATCACA-3′. Following PCR amplification, PCR products were digested with Bsr S1 for 2 h at 65°C and analysed on 8% polyacrylamide gels, run in 1 × TBE buffer at 200 V for 2 h. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide and DNA bands visualised on a UV transilluminator. Samples without the K-Ras codon 117 mutation were resistant to digestion and produced a single band of 288 bp, whereas samples homozygous for the codon 117 mutation were digested to produce bands of 271 and 17 bp. Heterozygous samples produced bands of 288, 271 and 17 bp. Band sizes were determined by comparison with ΦX174 DNA size markers (Promega).

RFLP analysis of K-Ras codon 146 mutations

Similarly, a PCR-RFLP assay was designed to identify the K-Ras codon 146 mutation, where the presence of the mutation created a recognition site for the restriction enzyme Mse I. A 197 bp PCR product was amplified using the primers 5′ TGG AAT TCC TTT TAT TGA AAC ATC A 3′ and 5′ GAT TAA GAA GCA ATG CCC TCT C 3′. Following PCR amplification, PCR products were digested with Mse1 for 2 h at 37°C and analysed on 8% polyacrylamide gels as described above. Samples without the K-Ras codon 146 mutation were digested to produce bands of 101, 91 and 5 bp, whereas samples homozygous for the codon 146 mutation produced bands of 91, 78, 23 and 5 bp. Heterozygous samples produced bands of 101, 91, 78, 23 and 5 bp.

RFLP analysis of K-Ras codon 164 mutations

The presence of the codon 164 mutation was confirmed using a novel RFLP assay, wherein the presence of the mutation destroyed a recognition site for the restriction enzyme BstBI. A 261 bp PCR product was generated as described above for K-Ras exon 4B mutation detection. After PCR amplification, PCR products were digested with BstBI for 2 h at 65°C and analysed on 2% agarose gels. Samples without the codon 164 mutation were digested to produce bands of 203 and 58 bp, whereas samples homozygous for the mutation produced a single band of 261 bp. Heterozygous samples produced bands of 261, 203 and 58 bp.

RFLP analysis of K-Ras codon 173 single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)

The codon 173 SNP was detected using a novel RFLP assay, where the presence of the mutation destroyed a recognition site for the restriction enzyme BccI. A 261 bp PCR product was generated as described above for K-Ras exon 4B mutation detection. After PCR amplification, PCR products were digested with BccI for 2 h at 37°C and analysed on 2% agarose gels. Samples without the codon 173 SNP were digested to produce bands of 173 and 88 bp, whereas samples homozygous for the codon 173 SNP produced a single band of 261 bp. Heterozygous samples produced bands of 261, 173 and 88 bp.

RFLP analysis of B-Raf V599E mutation

The B-Raf V599E mutation was detected using a novel RFLP assay, where the presence of the mutation destroyed a recognition site for the restriction enzyme TspRI. A 224 bp PCR product was amplified using the primers 5′-TCATAATGCTTGCTCTGATAGGA-3′ and 5′-GGCCAAAAATTTAATCAGTGGA-3′ in a 50 ml reaction containing 1 × PCR buffer (Promega), 1.25 mM MgCl2, 200 mM dNTPs, 300 nM primers, 6% DMSO and 1.5 U of Taq polymerase in a PCR as described above. After PCR amplification, PCR products were digested with TspR1 for 2 h at 37°C and analysed on 8% polyacrylamide gels as described above. Samples without the B-Raf V599E mutation were digested to produce bands of 124, 78 and 22 bp, whereas samples homozygous for the V599E mutation produced bands of 202 and 22 bp. Heterozygous samples produced bands of 202, 124, 78 and 22 bp.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, G., Bounds, R., Wolf, H. et al. Activating K-Ras mutations outwith ‘hotspot’ codons in sporadic colorectal tumours – implications for personalised cancer medicine. Br J Cancer 102, 693–703 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605534

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605534

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Differences in gynecologic tumor development in Amhr2-Cre mice with KRASG12D or KRASG12V mutations

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Signal transduction pathway mutations in gastrointestinal (GI) cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

The effects of mutant Ras proteins on the cell signalome

Cancer and Metastasis Reviews (2020)

-

Small Molecule KRAS Agonist for Mutant KRAS Cancer Therapy

Molecular Cancer (2019)

-

Different next-generation sequencing pipelines based detection of tumor DNA in cerebrospinal fluid of lung adenocarcinoma cancer patients with leptomeningeal metastases

BMC Cancer (2019)