Abstract

Background:

To implement distress screening in routine radiotherapy practice and to compare computerised and paper-and-pencil screening in terms of acceptability and utility.

Methods:

We used the Stress Index RadioOncology (SIRO) for screening. In phase 1, 177 patients answered both a computerised and a paper version, and in phase 2, 273 patients filled out either the computerised or the paper assessment. Physicians received immediate feedback of the psycho-oncological results. Patients, nurses/radiographers (n=27) and physicians (n=15) evaluated the screening procedure.

Results:

The agreement between the computerised and the paper assessment was high (intra-class correlation=0.92). Patients’ satisfaction did not differ between the two administration modes. Nurses/radiographers rated the computerised assessment less time consuming (3.7 vs 18.5%), although the objective data did not reveal a difference in time demand. Physicians valued the psycho-oncological results as interesting and informative (46.7%). Patients and staff agreed that the distress screening did not lead to an increase in the discussion of psychosocial issues in clinician–patient encounters.

Conclusion:

The implementation of a distress screening was feasible and highly accepted, regardless of the administration mode. Communication trainings should be offered in order to increase the discussion of psychosocial topics in clinician–patient encounters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Already at the outset of radiation therapy, many cancer patients experience a reduction in quality of life (Janda et al, 2004), reduced physical capacity and pain (Sehlen et al, 2001), or emotional distress (Faller et al, 2003). Reasonable as well as exaggerated worries about the effects of radiotherapy are not uncommon (Halkett et al, 2008), and the psychosocial stress level often remains high, or even increases, during and after radiotherapy (Sehlen et al, 2002, 2003b; Chen et al, 2009). Studies showed that about 50% of radiotherapy patients suffer from some mental disorder (Leopold et al, 1998; Fritzsche et al, 2004), underlining the need for psychosocial treatment.

One problem in detecting treatment need is the multitude of possible criteria (Herschbach, 2006). Investigations revealed that between 12 and 43% of radiotherapy patients showed a need for psychosocial treatment, depending on the criteria used (Söllner et al, 2001; Faller et al, 2003; Fritzsche et al, 2004; Hahn et al, 2004). In addition, there are further problems in screening and detecting treatment need, which are not limited to radiotherapy. First, the concordance between patient's self-defined treatment need and need defined by oncologists or by symptom checklists is low (Söllner et al, 2001; Fritzsche et al, 2004; Garssen and de Kok, 2008). Second, oncology professionals are reluctant to apply distress screening instruments, mainly due to lack of time and lack of training (Mitchell et al, 2008). Unfortunately, the detection of distress often does not lead to adequate psychosocial treatment (Garssen and de Kok, 2008; Mitchell et al, 2008). Finally, there is a lack of studies showing the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of implementing distress screening in routine practice (Kruijver et al, 2006; Garssen and de Kok, 2008; Mitchell et al, 2008). Despite these difficulties, several agencies promote the routine use of distress screening devices as the primary tool to detect psychosocial treatment need. For example, the American National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that all patients be screened for distress at their initial visit and at intervals thereafter (see Carlson and Bultz, 2003).

In the recent years, several studies investigated the use of computerised screening in oncology, which may be preferable over paper assessment because of convenience and feasibility. Computerised assessment may also circumvent the problem of oncologists’ lack of training in the psychosocial assessment of patients. Studies showed good agreement between computer and paper assessment (Velikova et al, 1999), as well as high acceptance and usability, even among older patients and those untrained in using a computer (Allenby et al, 2002; Wright et al, 2003; Mullen et al, 2004; Carter et al, 2008). Some studies suggest that computerised assessment is more convenient and time saving than paper assessment (Lane et al, 2006; Dale and Hagen, 2007). However, there is a lack of studies on computerised assessment in routine radiotherapy practice. Although some investigations included subsamples of patients undergoing radiotherapy (Allenby et al, 2002; Fann et al, 2009; Verdonck-de Leeuw et al, 2009), to our knowledge there is only one small study that focused exclusively on the radiotherapy setting (Berry et al, 2004; Mullen et al, 2004).

The aim of this work was to implement a computerised distress screening procedure in routine radiotherapy practice and to compare computerised and conventional paper-and-pencil assessment in terms of acceptability and utility. In contrast to the majority of research, we applied a psychosocial distress screening instrument specifically developed for use in radiotherapy – the Stress Index RadioOncology (SIRO) (Sehlen et al, 2003a).

Materials and methods

General overview

This was a two-phase study using two independent samples. In the first phase, we investigated the validity of the computerised screening and defined a clinical cutoff score of the SIRO. In the second phase, the screening procedure was implemented in routine radiotherapy care. Patients and staff reported on their satisfaction with the routine screening and the assessment mode. The study was conducted in two university clinics in Munich, Germany. The protocol received approval from the local ethics committee. Table 1 briefly summarises the different steps of this investigation and provides an overview of the assessments used.

Phase 1 – Validating the computerised assessment

Patients

Cancer patients who would be treated with radiotherapy for at least 2 weeks were sampled consecutively for 3 months in two clinics. The inclusion criteria used were as follows: age ⩾18 years old and Karnofsky performance status ⩾50. The exclusion criteria used were insufficient command of the German language, severe cognitive impairment (clinical assessment by the physician), whole body radiation therapy, brachytherapy as the sole treatment modality, stereotactical irradiation, hypofractionated radiotherapy with a treatment duration of less than 2 weeks and participation in a further clinical study. Treatment intent (curative or palliative) did not affect study participation. During 3 months, N=180 patients who complied with the criteria were approached, and all agreed to participate. Of those, n=177 (98.3%) provided data on the SIRO in both administration modes and therefore represent the final sample. The patients were 58.0 years old on average (s.d.=13.4, range 25–87). The leading diagnoses were breast and prostate cancer (see Table 2).

Procedure

Patients were approached after the second radiotherapy fraction within the first treatment week to provide informed consent and to fill out the SIRO. The computerised version was used first and the paper version second in one clinic, and vice versa in the other clinic. The time frame for the completion of the SIRO in the two different modalities ranged from 3 to 7 days. During the first of the two assessments, the patients additionally filled out measures of psychological distress. A subsample of patients was assessed with an interviewer-administered distress screening (see Herschbach et al, 2008; Siedentopf et al, 2010), which will not be reported here.

Assessment

The SIRO (Sehlen et al, 2003a) was used as a specific psychosocial distress screening. The SIRO measures the current level of perceived stress with 24 items that are rated on a five-point scale from 1 (‘nearly no burden’) to 5 (‘very high burden’), with the additional response option ‘does not apply’. The SIRO comprises four subscales: psychophysical distress, relationship difficulties, radiotherapy-induced distress and information deficits. Reliability of the complete scale is α=0.90, and convergent and discriminative validity were established (Sehlen et al, 2003a). For the computerised assessment, the items were presented on a tablet-PC. We used Windows XP Tablet PC Edition, and AnyQuest for Windows as software (see www.ql-recorder.com).

Anxiety and depression were assessed with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Hermann-Lingen et al, 1995). The two dimensions are measured with seven items per scale. Reliability and validity of the scales were proven in several studies (Hermann-Lingen et al, 1995; Olssøn et al, 2005).

Phase 2 – Implementing and evaluating computerised screening

Patients

Cancer patients were sampled in the same two clinics as in phase 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were the same as in the first phase. Over the course of 6 months, 358 patients who complied with the criteria were asked for study participation; 41 patients declined participation, and 44 patients were excluded as they did not provide an evaluative judgement. Thus, n=273 (76.3%) patients represent the final sample. They were 60.4 years old on average (s.d.=11.2; range 19–84); n=142 had answered the computerised version, and n=131 had filled out the paper assessment. Both groups were comparable with regard to sociodemographic and clinical variables (see Table 2).

Staff

Nurses/radiographers (n=27) and physicians (n=15) provided their evaluations anonymously. Thus, no sociodemographic data are available for the two professional groups.

Procedure

Implementation in routine care: Patients were approached soonest at their second treatment date. Having provided informed consent, the patients were asked to fill out the SIRO. In one clinic, the computerised version was used for the first 3 months and the paper-and-pencil version for the second 3 months of the study, and vice versa in the second clinic. For the paper version, the nurse or the radiographer entered the data in a PC after the patient had answered the SIRO. For the computerised assessment, the data were transferred using bluetooth technology. Next, the results sheet was printed out and deposited in the post box of the treating radiation oncologist. The physician was expected to read the results sheet, which she/he proofed by signature. If the SIRO total score indicated psychosocial distress (easy to realise through a highlighted bar), the treating physician was to call the division for psychosocial oncology for a consultation–liaison (C–L) intervention. The research assistants tracked which of the patients who scored above the cutoff actually received a psycho-oncological intervention.

Evaluation of the computerised and the conventional assessment: The patients evaluated the computerised or the conventional paper assessment of the SIRO at least 1 week after their assessment. Those patients for whom psychosocial care was initiated evaluated the SIRO procedure before their first appointment with the C–L psycho-oncologist in order to avoid confounding with the experience of professional support provision. Nurses, radiographers and physicians evaluated the implementation of the routine screening in the final phase of this study, shortly before the collection of the data was terminated.

For both SIRO administration modes, members of the project team took the time nurses/radiographers needed to instruct the patient and the time entering the data and printing out the results sheet. Each nurse/radiographer was observed once handling the computerised assessment and once providing the paper assessment.

Assessment

Besides the SIRO, the following measures were applied:

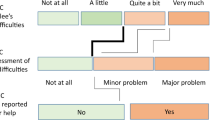

Evaluation of the computerised and the paper assessments was carried out with several evaluative items newly designed for this study:

Patients responded ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to 17 items. Nurses/radiographers and physicians answered 12 items on a five-point scale from ‘completely untrue’ to ‘completely true’. Here, we report only on those items referring to the implementation of the screening procedure, the usability of the two assessment modalities and the satisfaction with the assessment.

Patient satisfaction was assessed with two questionnaires:

Questions on Patient Satisfaction (Fragen zur Patientenzufriedenheit, FPZ; Henrich et al, 2001): This questionnaire comprises 10 items relating to different aspects of patient care. The items are rated on a five-point scale ranging from ‘unsatisfied’ (1) to ‘very satisfied’ (5). Each item is also rated with regard to subjective importance, ranging from ‘unimportant’ (1) to ‘extremely important’ (5). A total score is computed by weighing the satisfaction ratings with the respective importance ratings. As some items were inapplicable for outpatients, we used only the four items applicable for in- and outpatients to compute a summary score. These four items mainly focus on health-care staff–patient interaction. The internal consistency of this shortened scale was α=80. In addition, the FPZ contains a checklist of 42 possible suggestions for improvement of patient care (e.g. quality of breakfast, waiting times), which are not in the focus of the current report. Investigations showed the validity and utility of FPZ (Henrich et al, 2001; Gündel et al, 2007).

Satisfaction questionnaire (Patientenfragebogen zur Erfassung der Zufriedenheit, ZUF-8; Schmidt et al, 1989): This measure focuses on the satisfaction with the hospital and the care received. It contains eight items that are rated on a four-point scale, with different response options. The items are summed to form a total score. The reliability of this measure in the current sample was α=85. Validity has been established (Kriz et al, 2008).

Statistical analysis

Correlations were computed to measure the convergence between the computerised and the paper assessment of the SIRO. A receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was carried out in order to establish a cutoff score. We applied descriptive statistics, χ2 tests and paired sample as well as independent sample t-tests using SPSS 15 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Phase 1

The SIRO was administered without difficulty in both administration modes. The mean of the SIRO total score-paper version (M=1.56; s.d.=1.03) did not differ from the SIRO total score-computer version (M=1.54; s.d.=0.94); t (176)=−0.486, P>0.05. The correlation coefficients between the computerised SIRO and its paper assessment counterpart are given in Table 3. The results showed a high convergence between the two versions, with an intra-class correlation (ICC) for the complete scale of r=0.92.

The data of the computerised SIRO version were used for the development of the clinical cutoff. Clinical anxiety or depression, assessed with the HADS, represented the criteria against which the SIRO cutoff was established. The mean of the HADS anxiety subscale was M=6.23 (s.d.=4.40); the mean of the depression subscale was M=5.93 (s.d.=4.80), n=175. We used a cutoff ⩾11 for both the HADS anxiety and HADS depression subscale. This cutoff was applied in several studies as indicator of clinically relevant distress (Sellick and Edwardson, 2007; Hinz et al, 2010). The ROC analysis suggested a SIRO cutoff of ⩾1.90 (sensitivity 74%, specificity 77%, AUC 0.820). The prevalence of psychosocial distress, applying this cutoff, was 34.5% (n=61).

Phase 2

The mean of the SIRO, across the two administration modalities, was 1.31 (s.d.=0.87). Of the 273 participating patients, 23.8% (n=65) scored above the SIRO cutoff and, thus, indicated psychosocial distress. All of these patients should have been referred for the C–L intervention; 73.8% (n=48) actually had an appointment with the psycho-oncologist. The rate of the treating physicians who had signed the SIRO results sheet did not differ between the two SIRO administration arms (84.5 vs 84.7%).

The patients’ evaluations of the two administration procedures are shown in Table 4. The results reveal high acceptance and good comprehensibility of the SIRO in both administration modes. In total, 7.0 and 5.0%, respectively, of the patients reported that they had talked with the physician about the screening results, and 10.0 and 8.0%, respectively, had talked with the nurse.

Table 5 presents the results of the staffs’ evaluation of the implementation of the distress screening. Of the nurses/radiographers, 18.0% evaluated the paper version as time consuming, as opposed to 3.0% for the computer version. In all, 7.0% acknowledged an increased sensitivity for patients’ psychosocial stress due to the assessment procedures. The physicians found the results sheet comprehensible and interesting, and they showed high acceptance of the computerised assessment. Again, the assessment of the patients’ psychosocial distress did not lead to a marked increase of psychosocial communication topics in the physician–patient communication. Of the physicians, 8.0% stated that they had talked with the patient about the results of the distress assessment in routine interactions.

With regard to the general patient satisfaction, the results obtained with the modified FPZ were significant. The patients who were administered the paper assessment were more satisfied (n=120) than the patients who filled out the computerised version (n=112); t (230)=3.58, P<0.001. However, the two groups (n=125, n=124) did not differ in the ZUF-8 satisfaction rating; t (247)=−0.45, P>0.05 (see Table 6).

The time demand for the staff (n=27) differed for the two steps. Instructing the patient took longer with the computerised administration than with the paper assessment; t (26)=3.91, P<0.01. In contrast, data handling was faster with the computerised than with the paper assessment; t (26)=−8.35, P<0.001. However, there was no difference in staff's time demand in total time; t (26)=−0.396, P>0.05 (see Table 6).

Discussion

The routine collection of data on patient's psychosocial distress is feasible in routine radiotherapy practice. Our study did not provide clear evidence for the superiority of either one assessment mode. The patients’ evaluations did not differ between the computerised and the conventional paper assessment, both were highly accepted. However, the nurses/radiographers tended to rate the computerised version less time consuming. However, even for the paper assessment, only a minority stated that the assessment procedure was too long.

Despite these positive evaluations, the nurses/radiographers did not experience a positive impact of the distress screening on the discussion of patients’ psychosocial issues in the team. Physicians stated heightened personal interest in patients’ psychosocial issues due to the distress screening. However, they also reported that the distress screening itself and the screening results generally did not enter the realm of physician–patient communication – an observation that was shared by the patients.

This result of our study adds to the slowly accumulating evidence about the clinical consequences of the assessment of distress and patient reported outcomes (PRO). Some recent reviews in oncology (Kruijver et al, 2006; Luckett et al, 2009) and other fields of medicine (Greenhalgh et al, 2005; Valderas et al, 2008) conclude that feedback of PROs has little impact on patient management and patient outcomes. There seems to be some positive effect of PRO feedback on physician–patient interaction, however. In one of those studies in routine oncology practice (Velikova et al, 2004), which showed a positive impact on communication, physicians were trained in interpreting quality of life data. Furthermore, they were encouraged to make use of the information during all encounters. In our study, the physicians were instructed to call the psycho-oncologist in case of treatment need, as assessed by the distress screening procedure. Therefore, the physicians might have felt less committed to the idea of discussing the results of the distress screening, regardless of its administration mode. Thus, our results tentatively suggest that with increasing specialisation of care, there is the risk of increasing division of labour and diffusion of responsibility.

It seems to be desirable that oncologists communicate with the patient about the results of a distress screening, even if the patient is referred to C–L psycho-oncological care. However, in this case, there is the need for an explicit agreement and plan of action between the parties involved. It might even be desirable that oncologists use the feedback in case of absent increased distress in order to reinforce the patient's successful coping. Some data show that the use of PRO measures in managing patients does not increase consultation length (Luckett et al, 2009), but this can only be satisfactorily achieved if the physician can rely on good communication skills.

With regard to the validity and technical issues of the computerised and the conventional paper assessment of the SIRO, our results are in line with most of the available research. There was high congruence between the two assessment modes, and it can be concluded that mode of administration does not make a difference with regard to the reliability and validity of the SIRO (see Gwaltney et al, 2008; Velikova et al, 1999). The total duration of assessment turned out to be quite identical for both modalities. Finally, the two screening modalities did not differentially impact on the patients’ general satisfaction with the hospital and the care received, but there was a difference on the more specific measure of patient satisfaction with care (modified FPZ). To speculate, the patients who filled out the paper assessment might have expressed higher satisfaction with care as they experienced more interaction with staff and a less ‘technical’ atmosphere when filling out the SIRO.

Limitations of our study pertain to the research design, as only a randomised controlled trial would provide strong evidence concerning differential utility of the two assessment modalities. Furthermore, we did not ask the patients about their familiarity with computers. However, the patients indicated no problems in using the touch screen.

To conclude, the implementation of a routine distress screening with immediate feedback to the physician was feasible and highly accepted and resulted in high referral rates to a C–L psycho-oncological intervention. Computerised assessment was valued by the professionals, but it was not preferred above the conventional paper assessment by the patients. As the distress screening and the feedback of the results did not lead to an increase in the communication about psychosocial issues in the clinician–patient encounter, it seems necessary to offer communication trainings for clinicians (see Rodin et al, 2009), or to implement clinical supervision in order to strengthen reflective clinical practice.

Change history

29 March 2012

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Allenby A, Matthews J, Beresford J, McLachlan SA (2002) The application of computer touch-screen technology in screening for psychosocial distress in an ambulatory oncology setting. Eur J Cancer Care 11: 245–253

Berry DL, Trigg LJ, Lober WB, Karras BT, Galligan ML, Austin-Seymour M, Martin S (2004) Computerized symptom and quality-of-life assessment for patients with cancer. Part I: development and pilot testing. Oncol Nurs Forum 31: e75–e83

Carlson LE, Bultz BD (2003) Cancer distress screening. Needs, models, and methods. J Psychosom Res 55: 403–409

Carter G, Lewin T, Rashid G, Adams C, Clover K (2008) Computerised assessment of quality of life in oncology patients and carers. Psychooncology 17: 26–33

Chen AM, Jennelle RLS, Grady V, Tovar A, Bowen K, Simonin P, Tracy J, McCrudden D, Stella JR, Vijayakumar S (2009) Prospective study of psychosocial distress among patients undergoing radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 73: 187–193

Dale O, Hagen KB (2007) Despite technical problems personal digital assistants outperform pen and paper when collecting patient diary data. J Clin Epidemiol 60: 8–17

Faller H, Olshausen B, Flentje M (2003) Emotional distress and needs for psychosocial support among breast cancer patients at start of radiotherapy. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 53: 229–235

Fann JR, Berry DL, Wolpin S, Austin-Seymour M, Bush N, Halpenny B, Lober WB, McCorkle R (2009) Depression screening using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 administered on a touch screen computer. Psychooncology 18: 14–22

Fritzsche K, Liptai C, Henke M (2004) Psychosocial distress and need for psychotherapeutic treatment in cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol 72: 183–189

Garssen B, de Kok E (2008) How useful is a screening instrument? Psychooncology 17: 726–728

Greenhalgh J, Long AF, Flynn R (2005) The use of patient reported outcome measures in routine clinical practice: lack of impact or lack of theory? Soc Sci Med 60: 833–843

Gündel H, Hümmeler V, Lordick F (2007) Which tumor patients profit from interdisciplinary psychoeducation in the framework of a tumor therapy? Z Psychosom Med Psychother 53: 324–338

Gwaltney CJ, Shields AL, Shiffman S (2008) Equivalence of electronic and paper-and-pencil administration of patient-reported outcome measures: a meta-analytic review. Value Health 11: 322–333

Hahn CA, Dunn R, Halperin EC (2004) Routine screening for depression in radiation oncology patients. Am J Clin Oncol 27: 497–499

Halkett GKB, Kristjanson LJ, Lobb EA (2008) ‘If we get too close to your bones they’ll go brittle’: women's initial fears about radiotherapy for early breast cancer. Psychooncology 17: 877–884

Henrich G, Herschbach P, Schäfer I (2001) Questions on patient satisfaction (FPZ) – the development of a questionnaire. Z Med Psychol 10: 147–158

Hermann-Lingen C, Buss U, Snaith RP (1995) Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Deutsche Version. Huber: Bern

Herschbach P (2006) The need for treatment in psychooncology. Principles and assessment strategies. Onkologe 12: 41–47

Herschbach P, Book K, Brandl T, Keller M, Lindena G, Neuwöhner K, Marten-Mittag B (2008) Psychological distress in cancer patients assessed with an expert rating scale. Br J Cancer 31: 591–596

Hinz A, Krauss O, Hauss JP, Höckel M, Kortmann RD, Stolzenburg JU, Schwarz R (2010) Anxiety and depression in cancer patients compared with the general population. Eur J Cancer Care 19: 522–529

Janda M, Newman B, Obermair A, Woelfl H, Trimmel M, Schroeckmayr H, Widder J, Poetter R (2004) Impaired quality of life in patients commencing radiotherapy for cancer. Strahlenther Onkol 180: 78–83

Kriz D, Nübling R, Steffanowski A, Wittmann WW, Schmidt J (2008) Patients’ satisfaction in inpatient rehabilitation: psychometrical evaluation of the ZUF-8 based on a multicenter sample of different indications. Z Med Psychol 17: 67–79

Kruijver IPM, Garssen B, Visser AP, Kuiper AJ (2006) Signalising psychosocial problems in cancer care. The structural use of a short psychosocial checklist during medical or nursing visits. Patient Educ Couns 62: 163–177

Lane SJ, Heddle NM, Arnold E, Walker I (2006) A review of randomized controlled trials comparing the effectiveness of hand held computers with paper methods for data collection. BMC Med Inform Dec Making 6: 23

Leopold KA, Ahles TA, Walch S, Amdur RJ, Mott LA, Wiegand-Packard L, Oxman TE (1998) Prevalence of mood disorders and utility of the PRIME-MD in patients undergoing radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 42: 1105–1112

Luckett T, Butow PN, King MT (2009) Improving outcomes through the routine use of patient-reported data in cancer clinics: future directions. Psychooncology 18: 1129–1138

Mitchell AJ, Kaar S, Coggan C, Herdman J (2008) Acceptability of common screening methods used to detect distress and related mood disorders – preferences of cancer specialists and non-specialists. Psychooncology 17: 226–236

Mullen KH, Berry DL, Zierler BK (2004) Computerized symptom and quality-of-life assessment for patients with cancer. Part II: acceptability and usability. Oncol Nurs Forum 31: e84–e89

Olssøn I, Mykletun A, Dahl AA (2005) The Hospital Anxiety and Depression rating scale: a cross-sectional study of psychometrics and case finding abilities in general practice. BMC Psychiatry 5: 46

Rodin G, Mackay JA, Zimmermann C, Mayer C, Howell D, Katz M, Sussman J, Brouwers M (2009) Clinician–patient communication: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 17: 627–644

Schmidt J, Lamprecht F, Wittmann WW (1989) Satisfaction with inpatient management. Development of a questionnaire and initial validity studies. Psychother Psyosom Med Psychol 39: 248–255

Sehlen S, Fahmüller H, Herschbach P, Aydemir U, Lenk M, Dühmke E (2003a) Psychometric properties of the Stress Index RadioOncology (SIRO) – a new questionnaire measuring quality of life of cancer patients during radiotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol 179: 261–269

Sehlen S, Hollenhorst H, Lenk M, Schymura B, Herschbach P, Aydemir U, Dühmke E (2002) Only sociodemographic variables predict quality of life after radiotherapy in patients with head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 52: 779–783

Sehlen S, Hollenhorst H, Schymura B, Firsching M, Aydemir U, Herschbach P, Dühmke E (2001) Disease specific stress of tumor patients at the beginning of radiotherapy. Effect on psychosocial support requirement. Strahlenther Onkol 177: 530–537

Sehlen S, Hollenhorst H, Schymura B, Herschbach P, Aydemir U, Firsching M, Dühmke E (2003b) Psychosocial stress in cancer patients during and after radiotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol 179: 175–180

Sellick SM, Edwardson AD (2007) Screening new cancer patients for psychological distress using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Psychooncology 16: 534–542

Siedentopf F, Marten-Mittag B, Utz-Billing I, Schoenegg W, Kentenich H, Dinkel A (2010) Experiences with a specific screening instrument to identify psychosocial support needs in breast cancer patients. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 148: 166–171

Söllner W, DeVries A, Steixner E, Lukas P, Sprinzl G, Rumpold G, Maislinger S (2001) How successful are oncologists in identifying patient distress, perceived social support, and need for psychosocial counselling? Br J Cancer 84: 179–185

Valderas JM, Kotzeva A, Espallargues M, Guyatt G, Ferrans CE, Halyard MY, Revicki DA, Symonds T, Parada A, Alonso J (2008) The impact of measuring patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res 17: 179–193

Velikova G, Booth L, Smith AB, Brown PM, Lynch P, Brown JM, Selby PJ (2004) Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 22: 714–724

Velikova G, Wright AB, Smith AB, Cull A, Gould A, Forman D, Perren T, Stead M, Brown J, Selby PJ (1999) Automated collection of quality-of-life data: a comparison of paper and computer touch-screen questionnaires. J Clin Oncol 17: 998–1007

Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, de Bree R, Keizer AL, Houffelaar T, Cuijpers P, van der Linden MH, Leemans CR (2009) Computerized prospective screening for high levels of emotional distress in head and neck cancer patients and referral rate to psychosocial care. Oral Oncol 45: e129–e133

Wright EP, Selby PJ, Crawford M, Gillibrand A, Johnston C, Perren TJ, Rush R, Smith A, Velikova G, Watson K, Gould A, Cull A (2003) Feasibility and compliance of automated measurement of quality of life in oncology practice. J Clin Oncol 21: 374–382

Acknowledgements

We thank Jörg M Sigle for programming the electronic version of the SIRO. This research was supported by Deutsche Krebshilfe e.V.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Dinkel, A., Berg, P., Pirker, C. et al. Routine psychosocial distress screening in radiotherapy: implementation and evaluation of a computerised procedure. Br J Cancer 103, 1489–1495 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605930

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605930

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Evaluation of an electronic psycho-oncological adaptive screening program (EPAS) with immediate patient feedback: findings from a German cluster intervention study

Journal of Cancer Survivorship (2022)

-

Investigation of the Spiritual Care Effects on Anxiety, Depression, Psychological Distress and Spiritual Levels of Turkish Muslim Radiotherapy Patients

Journal of Religion and Health (2021)

-

Screen2Care – digitale Erfassung von psychoonkologischem Unterstützungsbedarf

Der Onkologe (2020)

-

Cancer patients’ wish for psychological support during outpatient radiation therapy

Strahlentherapie und Onkologie (2018)

-

Patient-reported outcome use in oncology: a systematic review of the impact on patient-clinician communication

Supportive Care in Cancer (2018)