Abstract

Human thioredoxin (TRX) was first identified in human T-cell leukemia virus type I (HTLV-I)-positive T-cell lines and is associated with the pathophysiology of retroviral infections. TRX is a vital component of the thiol-reducing system and regulates various cellular function (redox regulation). Members of the TRX system regulate apoptosis through a wide variety of mechanisms. A family of thioredoxin-dependent peroxidases (peroxiredoxins) protects against apoptosis by scavenging hydrogen peroxide. Thioredoxin 2 is a critical regulator of cytochrome c release and mitochondrial apoptosis; transmembrane thioredoxin-related molecule (TMX) has a protective role in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress-induced apoptosis. TRX interacts with apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) and is a sensor of oxidative stress. Thioredoxin binding protein-2/vitamin D3 upregulated protein 1 is a growth suppressor and its expression is suppressed in HTLV-I-transformed cells. Studies of these molecules of the TRX system provide novel insights into the apoptosis associated with retroviral diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Thioredoxin (TRX) System and Regulation of Apoptosis Signal

TRX

The cellular reducing environment is provided by two mutually interconnected systems; the TRX system and the glutathione (GSH) system. Under physiological conditions, the intracellular reducing environment is maintained by the disulfide/dithiol-reducing activity of the GSH and TRX systems. GSH is a cysteine-containing tripeptide (γ-glutamyl-cysteinyl-glycine), which is a major component of cytosolic antioxidant. TRX is a small protein with two redox-active cysteine residues in its active center (–Cys–Gly–Pro–Cys–) and operates together with NADPH and thioredoxin reductase as an efficient reducing system for exposed protein disulfides (Figure 1).1 While the amount of TRX (micromolar concentration) is much less than that of GSH (millimolar concentration), TRX and GSH play distinct roles in maintaining cellular environment. TRX enhances the binding of transcription factors to the target DNA more efficiently than GSH. TRX can directly associate in the nucleus with redox factor 1 (Ref-1), which is identical to a DNA repair enzyme, AP endonuclease, and both molecules through their redox-active cysteine residues augment the DNA-binding activity of transcription factors, such as activator protein 1 (AP-1) and p53.2, 3, 4 The components of the TRX system not only scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) but also play regulatory roles in a variety of cellular function through protein–protein interaction.5 Mice carrying the homozygously deleted TRX gene died shortly after implantation, suggesting that TRX is essential for cell survival and early development.6 TRX transgenic mice, which ubiquitously overexpress human TRX under the control of β-actin promoter, display various phenotypes, such as an elongated lifespan7 and protection against ischemic injury,8 acute lung failure,9 diabetes mellitus,10 and the toxicity caused by environmental stressors.11 Since oxidative stress has been implicated in these conditions, TRX seems to play an important role in protection against oxidative stress-associated diseases. In cooperation with peroxiredoxins (described below), TRX has an antiapoptotic effect by scavenging intracellular ROS through the dithiol at its active site (Figure 2). Intriguingly, S-nitrosylation at cysteine 69 is required for the reducing activity and antiapoptotic function.12

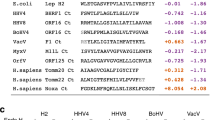

The role of the thioredoxin (TRX) system and related molecules in the regulation of apoptosis. Host cells exert multiple defense responses such as cell cycle control, apoptosis, and antioxidant induction against environmental stressors. The TRX system is composed of several related molecules forming a network of interactions with its active site cysteine residues, maintaining the cellular reducing environment and protecting cells from oxidative stress. TRX operates together with NADPH and TRX reductase as an efficient reducing system for exposed protein disulfides and cooperates with families of TRX-dependent peroxidases (peroxiredoxins) to scavenge intracellular hydrogen peroxide. The binding of transcription factors to DNA is positively modulated by TRX and apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease (Apex)/redox factor-1 (Ref-1). TRX also exerts its role through interaction with its binding proteins. TRX-binding protein-2 (TBP-2)/vitamin D3 upregulated protein 1 (VDUP1) plays an important regulatory role in growth control. TRX also interacts with apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1), an important regulator of apoptosis. When TRX is oxidized in response to oxidative stress, ASK1 is dissociated from the oxidized TRX and activated to induce an apoptotic signal

Interconnection among oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and mitochondrial apoptosis. Mammalian thioredoxin 2 (TRX2) is an essential regulator protecting cytochrome c release and apoptosis, whereas transmembrane thioredoxin-related molecule (TMX) plays a role counteracting ER-mediated apoptosis. Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) seems to not only sense oxidative stress but regulate both ER- and mitochondria-derived apoptosis signals

Oxidative stress and apoptosis

Our group reported that a thiol-oxidizing reagent, diamide, induces cell death. The cell death is either apoptosis or necrosis, depending on the concentration.13, 14 Intriguingly, diamide caused release of mitochondrial cytochrome c into the cytosol regardless of whether apoptosis or necrosis is induced. Since each caspase has a cysteine residue in its active site, the activity of caspase is regulated by the redox state (mainly by the TRX system).14 A disruption of caspase activity induced by oxidative stress resulted in a shift from apoptosis to necrosis. Taken together with the results of the hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis–necrosis shift,15 the intracellular redox state and redox-sensitive caspase activity seem to regulate the morphological changes of cell death. Cell death induced by oxidative stress appears to be apoptosis as long as the intracellular reducing status is maintained by the TRX system.14, 16

Proapoptotic signal including oxidative stress converges on mitochondria to induce mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization, which is lethal because it results in the release of proapoptotic caspases-activating molecules and caspases-independent death effectors and metabolic failure in mitochondria.17 Permeability transition pore complex consists of voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) localized in outer membrane, adenine nucleotide translocator (ANT) in inner membrane, and cyclophilin D in the matrix, and opening of the pore leads to loss of the mitochondrial transmembrane potential and swelling of the matrix.18 Since diamide-induced crosslinking of ANT mediates the membrane permeabilization, the function of ANT is regulated by the redox.19 Oxidative stress seems to decrease the threshold of the pore opening to induce mitochondria-mediated apoptosis.

Peroxiredoxins

The members of the TRX system form a network and maintain the cellular reducing environment. TRX scavenges intracellular hydrogen peroxide in collaboration with a family of thioredoxin-dependent peroxidases, peroxiredoxins.20 The mammalian peroxiredoxin family has six members expressed in several subcellular compartments, including peroxisomes and mitochondria, while catalase is present only in peroxisomes. Peroxiredoxins I and II are cytosolic proteins, whereas peroxiredoxin III is specifically expressed in mitochondria. Mammalian peroxiredoxin IV is found in the endoplasmic reticulum and lysosomes and also secreted into the extracellular space. Peroxiredoxin V is located in peroxisomes and mitochondria, while peroxiredoxin VI is in cytoplasm and mitochondria. All peroxiredoxins except type III also exsist in the nucleus. Peroxiredoxins I–V contain two cysteines, whereas peroxiredoxin VI has one cysteine for the catalytic activity. Peroxiredoxins protect cells against apoptotic stimuli.21, 22, 23 Mice deficient in peroxiredoxin I or II have hemolytic anemia, showing that erythrocytes are susceptible to oxidative stress. Peroxiredoxin knockout mice thus display milder phenotypes than TRX knockout mice, suggesting that the function of peroxiredoxins is redundant and can be partly compensated.24, 25

Thioredoxin 2 (TRX2), a regulator of apoptosis in mitochondria

Two independent pathways of apoptosis converge in mitochondria.26 Stress as well as death receptor-mediated activation of caspase-8 triggers the release of proapoptotic proteins, such as cytochrome c and apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF), from mitochondria, leading to the activation of downstream caspases (ex. caspase-3) and subsequent execution of apoptosis.27, 28 There is also a link between nuclei and mitochondria. In response to DNA double-strand breaks, histone H1.2 is released from the nucleus into the cytosol and induces cytochrome c release.29 Smac/DIABLO and HtrA2/Omi are also released from mitochondria upon receiving apoptotic stimuli and inhibit the functions of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs; endogenous inhibitors of caspases) by direct binding, leading to the activation of caspases.30, 31, 32 HtrA2/Omi has the serine protease activity, which seems to be required for the execution of cell death32 and could have other targets than IAPs.

Since mitochondria are at the center of several stress-induced apoptotic signaling pathways,17, 26 mitochondria have several protective mechanisms. Mitochondria contain large amount of GSH which may serve as a buffer against oxidative stress. Mammalian TRX2 is specifically expressed in mitochondria and essential for cell survival.33, 34 (Figure 2) TRX2 has a mitochondrial translocation signal peptide at the N-terminus and a conserved active disulfide/dithiol-like cytosolic TRX. In mammals, there are three thioredoxin reductases (TRXRs): cytosolic TRXR (TRXR1), mitochondrial TRXR (TRXR2),35, 36, 37 and testis-specific TRX glutathione reductase (TGR).38 In exquisite contrast to the cytosolic TRX system, which is composed of cytosolic peroxiredoxin (mainly peroxiredoxins I and II)–TRX–TRXR1, the TRX system in mitochondria consists of mitochondrial peroxiredoxin III–TRX2–TRXR2. In a conditional TRX2-deficient chicken B-cell line, DT-40, suppression of TRX2 expression caused the accumulation of intracellular ROS and induced cytochrome c release and subsequent apoptosis.34 TRX2 prevents mitochondria-mediated cell death by scavenging ROS generated in mitochondria, which are a major physiological source of ROS during respiration and pathological conditions (Figure 2). In addition, TRX2 might inhibit apoptotic signaling by anchoring cytochrome c in mitochondria, given that TRX2 associates directly with cytochrome c in vitro and in vivo,34 or interacting with another molecule in mitochondria (Wang et al., unpublished observation). Other reports also indicate the regulatory role of TRX2 in mitochondrial cell death. Overexpression of TRX2 confers an increase in mitochondrial membrane potential and resistance to etoposide-induced cell death.39 The knockout of TRX2 gene in mice is embryonic lethal, further indicating that TRX2 is indispensable for cell survival and that TRX and TRX2 cannot compensate for each other.6, 40 Recently, it was reported that mice lacking mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase (TRXR2) also die in the embryonic stage because of reduced myocardial function and perturbed hematopoiesis in the liver.41 The proapoptotic activity of another redox-active inducer of apoptosis, AIF, might be regulated by TRX or TRX2, although its function is reported to be independent of its NADH oxidase activity.42

Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1)

ASK1 was identified by Ichijo et al,43 as one of the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase kinase kinases that activates c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 MAP kinase and induces stress-mediated apoptotic signaling. TRX acts as a sensor of oxidative-stress-induced ASK1 activation. Reduced TRX binds to ASK1 and inhibits the activity of ASK1. Under oxidative stress, TRX is oxidized and dissociated from ASK1, resulting in the activation of ASK1.44 ASK1 is also activated in cells treated with TNF-α or cis-diamminedichloroplatinum (CDDP), indicating that ASK1 is involved in stress-induced apoptosis.44, 45 Constitutively activated ASK1 induces apoptosis through cytochrome c release and caspase activation, and caspase-9-deficient murine embryonic fibroblasts are resistant to ASK1 activation-induced cell death, indicating that ASK1 induces apoptosis through mitochondrial pathway.46

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-mediated stress activates caspase-12 and ASK1, resulting in mitochondria-mediated apoptosis.46, 47, 48, 49 ER stress induced by polyglutamine, which is the underlying cause of neurodegenerative diseases such as Huntington's disease, activates ASK1 through the formation of an IRE1–TRAF2–ASK1 complex, resulting in JNK activation and cell death.48, 50 Amyloid-β, a cause of Alzheimer's disease, induces ER stress through caspase-12 and ROS-mediated ASK1 activation, resulting in neuronal cell death.47, 51 These results show that ER stress is also partly linked to mitochondria through the activation of ASK1 during apoptosis. As discussed in this section, ASK1 interacts with various partners and is regulated through multiple mechanisms upon each stimulus. The precise molecular mechanism of ASK1 activation and how TRX regulates ASK1 in a physiological context should be further elucidated (Figure 2).

Transmembrane thioredoxin-related protein (TMX)

The protective role of TRX-related molecules against ER stress has been emphasized rather recently. TMX, a novel member of the TRX-related protein localized in ER, possesses a signal peptide at the N-terminus, followed by a TRX-like domain with an unique –Cys–Pro–Ala–Cys– sequence at the active site.52 TMX was abundant in membrane fractions and exhibited a similar subcellular distribution to calnexin localized to the ER. The N-terminal region containing the TRX-like domain was present in the ER lumen. Recombinant TMX showed protein disulfide isomerase (PDI)-like activity to refold scrambled RNase.53 Cells overexpressing TMX showed resistance to apoptosis induced by an ER–Golgi transport inhibitor, suggesting that TMX relieves ER stress.52 Since maturation of protein through disulfide bond formation and disulfide isomerization occurs in ER, the redox regulation plays a crucial role in protein quality control in ER and ER stress-mediated apoptosis.

Human T-cell Leukemia Virus Type-I (HTLV-I) Infection and the TRX System

Adult T-cell leukemia (ATL) was identified in 1970s as a distinct clinical entity based on its unique clinical features and is caused by human T-cell leukemia virus type I (HTLV-I).54, 55, 56, 57 ATL cells are CD3+CD4+CD8− in the majority of ATL cells with a characteristic constitutive expression of interleukin-2 (IL-2) and the α chain of the IL-2 receptor (IL-2Rα). The mean age of ATL patients at disease onset is 55 years. ATL is clinically classified into four types: acute, chronic, smoldering, and lymphoma types. Chronic type ATL is characterized by milder symptoms and signs and a longer clinical course, eventually leading to either an abrupt exacerbation of the disease or in fatal complications. ATL develops in 1–3% of infected individuals. The mechanisms of HTLV-I transformation and leukemogenesis are not yet fully elucidated. HTLV-I are also known to cause diseases such as HTLV-I-associated myelopathy (HAM)/tropical spastic paraparesis (TSP), HTLV-I associated arthropathy (HAAP), and HTLV-I-associated uveitis.58 The viral oncoprotein Tax, a 40-kDa transcriptional activator of HTLV-I, transactivates not only the genes of its own virus but also a set of cellular genes, including IL-2, IL-2Rα, IL-15R, IL-1, IL-6, IL-15, GM-CSF, Bcl-XL, and several immediate early response genes (c-fos, c-jun, fra-1, and c-myc).59, 60, 61, 62 Tax represses the transcription of certain genes such as DNA polymerase β, lck, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (p18), and p53 genes and functionally suppresses cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)4, p16INKa. Tax also interacts with CREB, p300, CBP, and PCAF.63 Tax is reported to protect cells from stress-induced apoptosis, whereas Tax is also reported to sensitize cells to stress-induced apoptosis. The cellular environment may influence the decision between proliferation and death by Tax.60 Although Tax seems to play a key role in T-cell transformation, ATL cells frequently lost the expression of Tax to escape from immune surveillance by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL).62 The low incidence of ATL among HTLV-I-infected carriers, together with a long latent period, suggests that multiple host–viral events in addition to Tax are involved in the progression of HTLV-I-dependent transformation and the subsequent development of ATL (Figure 3).61, 62

Role of cellular factors in the leukemogenesis of adult T-cell leukemia (ATL). ATL is caused by human T-cell leukemia virus type I (HTLV-I). Multiple host–viral events, including loss of growth suppressors such as thioredoxin-binding protein-2 (TBP-2), are involved in the progression of HTLV-I transformation and the subsequent development of ATL. The cellular environment may influence the decision between proliferation and apoptosis induced by Tax. ATL cells frequently lose the expression of Tax

Human TRX was identified in HTLV-I-positive T-cell lines64 as well as a growth-promoting factor derived from B-cell lines immortalized by Epstein–Barr virus (EBV).65 Thioredoxin expression was upregulated in HTLV-I-transformed T-cell lines.66 The enhanced TRX expression may cause augmented growth of HTLV-I- transformed cells and inhibit apoptosis. The mechanism of the upregulation may be partly explained by Tax-mediated transactivation67 and suppression of thioredoxin binding protein-2 (TBP-2), a negative regulator of TRX (described in detail in the next chapter).

TBP-2/VDUP1

We isolated TBP-2/vitamin D3 upregulated protein 1 (VDUP1), which was originally reported as the product of a gene whose expression was upregulated in HL-60 cells stimulated with 1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3.68, 69 The interaction of TBP-2/VDUP1 with TRX was observed in vitro and in vivo. Interestingly, TBP-2/VDUP1 only binds to the reduced form of TRX and acts as an apparent negative regulator of TRX.68 Later, other groups also reported the interaction between TRX and this protein.70, 71 Although the mechanism is unknown, a reciprocal expression pattern of TRX and TBP-2 was often reported upon various stimulation.72, 73

TBP-2 has a growth suppressive activity. Overexpression of TBP-2 was shown to result in growth suppression.74, 75, 76, 77 TBP-2 expression is upregulated by vitamin D3 treatment, serum or IL-2 deprivation, leading to growth arrest. However, the precise molecular function of TBP-2 is currently unclear. The role of TBP-2 expression in apoptosis caused by growth factor deprivation should be investigated. TBP-2 was found predominantly in the nucleus77 and may be a component of a transcriptional repressor complex.74 TBP-2 mRNA expression is downregulated in several tumors,72, 78 suggesting a close association between the reduction and tumorigenesis. TBP-2 expression is downregulated in melanoma metastasis.79

Loss of TBP-2 seems to be an important step of HTLV-I transformation. In an in vitro model, HTLV-I-infected T cells require IL-2 to proliferate in the early phase of transformation, but subsequently lose cell cycle control in the late phase, as indicated by their continuous proliferative state in the absence of IL-2. The change of cell growth phenotype has been suggested to be one of the oncogenic transformation processes.80 The expression of TBP-2 is lost in HTLV-I-positive IL-2-independent T-cell lines, but maintained in HTLV-I-positive IL-2-dependent T-cell lines as well as HTLV-I-negative T-cell lines.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection and the TRX System

HIV infection causes apoptosis in CD4+ T cells.81 The mechanism of HIV-induced apoptosis is complex and multifactorial.82 Dysregulation of the TRX system seems to be involved in apoptosis in HIV infection. Cells highly producing TRX, such as dendritic cells and activated macrophages in lymph nodes, decreased in number in HIV-infected lymph nodes. An in vitro infection of HIV on T-cell lines (SKT-1 and MT-2 cells) caused downregulation of protein expression of TRX 3 days after infection.83 HIV infection caused transient downregulation of the Bcl-2 and TRX protein expression in Jurkat and U937 cells, followed by restoration to the initial levels. Cells with decreased levels of these proteins were susceptible to apoptosis. The upregulation of Bcl-2 expression repressed viral replication, therefore, the state of low level viral replication may be favorable for cell survival, resulting in persistent infection.84 In monocytes from asymptomatic patients, the levels of Bcl-2 and TRX decreased, which is associated with enhanced hydrogen peroxide production, whereas in cells from AIDS patients the levels returned to normal.85 Peroxiredoxin family proteins NKEF-A and NKEF-B were upregulated in activated CD8+ T cells with HIV infection. T cells transfected with NKEF-A or NKEF-B were resistant to HIV infection.86 Protein expression of peroxiredoxin IV (AOE372) was reduced in T-cell lines (C81 and MT-2) that are acutely infected with high titers of HIV-1. Overexpression of peroxiredoxin IV (AOE372) in T cells inhibited HIV transcription through inactivation of HIV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR) and suppressed the level of HIVp24.87 The level of peroxiredoxin IV in T cells (C81) chronically infected with HIV was reduced. Although the regulatory mechanisms of the expression of TRX and peroxiredoxins in HIV infection may be varied and should be further elucidated, the redox balance affected by the intracellular TRX system seems to be important for cell survival and low viral production, probably leading to chronic persistent infection of HIV (Figure 4).

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and the thioredoxin (TRX) system. HIV infection causes changes of the expression of cellular defensive factors such as Bcl-2, TRX, and peroxiredoxins. The compensated redox balance seems to be important in cell survival and low viral production, probably leading to chronic persistent infection of HIV. As for the extracellular TRX, the plasma TRX level was elevated in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients and may reflect an involvement of oxidative stress or enhanced susceptibility to infection in advanced disease

As for extracellular TRX, the plasma TRX level was found to be elevated in HIV-infected patients,88 although the source of the increase remains unclear. Survival was significantly impaired when the plasma TRX level is chronically elevated in HIV-infected subjects with CD4+ T-cell counts below 200/μl blood.89 The elevated TRX level may reflect an involvement of oxidative stress or enhanced susceptibility to infection in advanced disease, according to the results that oxidative stress enhances the secretion of TRX. The impairment of survival in AIDS patients with chronically elevated TRX levels may be because normal immune defenses have been severely disrupted.

The redox system has been implicated in the pathophysiology of HIV infection as well as the regulation of apoptosis. Glutaredoxin (thioltransferase) is detected within HIV-1 and can regulate the activity of glutathionylated HIV protease in vitro. Although the physiological significance remains to be elucidated, the cysteine residues of the HIV protease coupled with glutaredoxin and GSH may optimize HIV protease activity particularly under conditions of oxidative stress.90 The conserved cysteines of the HIV protease are involved in the redox regulation of polyprotein processing and viral maturation of immature virions.91 The activity of HTLV-I protease can be also regulated through reversible glutathionylation of its conserved cysteine residues. The regulation of retroviral proteases may be a mechanism to prevent the premature activation of retroviral proteases with the cytoplasm of infected cells.92 The immunoglobulin-like domain D2 disulfide bond of CD4 is reported to be redox-active and reduced by TRX, indicating that the redox changes in CD4 are important for HIV entry.93 The physiological significance of these regulatory mechanisms by the redox system should be further investigated.

Summary and Future Perspectives

Here, we discussed that members and related molecules of the TRX system regulate apoptotic signaling through a wide variety of mechanisms and are closely associated with the pathophysiology of retroviral diseases. In spite of an accumulating knowledge on the molecular biology of HTLV-I, the mechanism of HTLV-I-mediated cellular transformation and leukemogenesis still remains unsolved. The molecular mechanism of persistent infection should be also elucidated to counteract the problem of resistance to intensive combinatory antiretroviral therapy. Since viruses seem to take advantage of the host defense machinery, the investigation of basic cellular regulatory mechanisms such as redox may provide novel insights into apoptosis research and approaches to treat retroviral diseases.

Abbreviations

- HTLV-I:

-

human T-cell leukemia virus type I

- ATL:

-

adult T-cell leukemia

- TBP-2:

-

thioredoxin-binding protein-2

- VDUP1:

-

vitamin D3 upregulated protein-1

- ASK1:

-

apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1

- ROS:

-

reactive oxygen species

- TMX:

-

transmembrane thioredoxin-related protein

- ER:

-

endoplasmic reticulum

- GSH:

-

glutathione

- TRX:

-

thioredoxin

- AIF:

-

apoptosis-inducing factor

- IAPs:

-

inhibitor of apoptosis proteins

- TRXR:

-

thioredoxin reductase

- IL-2:

-

interleukin-2

- IL-2Rα:

-

α chain of IL-2 receptor

- HIV:

-

human immunodeficiency virus

- AIDS:

-

acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- ANT:

-

adenine nucleotide translocator

References

Holmgren A and Björnstedt M (1995) Thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. Methods Enzymol. 252: 199–208

Ueno M, Masutani H, Arai RJ, Yamauchi A, Hirota K, Sakai T, Inamoto T, Yamaoka Y, Yodoi J, Sakai T and Nikaido T (1999) Thioredoxin-dependent redox regulation of p53-mediated p21 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 35809–35815

Hirota K, Matsui M, Iwata S, Nishiyama A, Mori K and Yodoi J (1997) AP-1 transcriptional activity is regulated by a direct association between thioredoxin and Ref-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94: 3633–3638

Sen CK and Packer L (1996) Antioxidant and redox regulation of gene transcription. FASEB J. 10: 709–720

Masutani H and Yodoi J (2002) Overview: thioredoxin. In: Methods Enzymol, Packer L (ed) (San Diego: Academic Press) pp. 279–286

Matsui M, Oshima M, Oshima H, Takaku K, Maruyama T, Yodoi J and Taketo MM (1996) Early embryonic lethality caused by targeted disruption of the mouse thioredoxin gene. Dev. Biol. 178: 179–185

Mitsui A, Hamuro J, Nakamura H, Kondo N, Hirabayashi Y, Ishizaki-Koizumi S, Hirakawa T, Inoue T and Yodoi J (2002) Overexpression of human thioredoxin in transgenic mice controls oxidative stress and life span. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 4: 693–696

Takagi Y, Mitsui A, Nishiyama A, Nozaki K, Sono H, Gon Y, Hashimoto N and Yodoi J (1999) Overexpression of thioredoxin in transgenic mice attenuates focal ischemic brain damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96: 4131–4136

Hoshino T, Nakamura H, Okamoto M, Kato S, Araya S, Nomiyama K, Oizumi K, Young HA, Aizawa H and Yodoi J (2003) Redox-active protein thioredoxin prevents proinflammatory cytokine- or bleomycin-induced lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 168: 1075–1083

Hotta M, Tashiro F, Ikegami H, Niwa H, Ogihara T, Yodoi J and Miyazaki J (1998) Pancreatic beta cell-specific expression of thioredoxin, an antioxidative and antiapoptotic protein, prevents autoimmune and streptozotocin-induced diabetes. J. Exp. Med. 188: 1445–1451

Yoon BI, Hirabayashi Y, Kaneko T, Kodama Y, Kanno J, Yodoi J, Kim DY and Inoue T (2001) Transgene expression of thioredoxin (TRX/ADF) protects against 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD)-induced hematotoxicity. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 41: 232–236

Haendeler J, Hoffmann J, Tischler V, Berk BC, Zeiher AM and Dimmeler S (2002) Redox regulatory and anti-apoptotic functions of thioredoxin depend on S-nitrosylation at cysteine 69. Nat. Cell Biol. 4: 743–749

Sato N, Iwata S, Nakamura K, Hori T, Mori K and Yodoi J (1995) Thiol-mediated redox regulation of apoptosis. Possible roles of cellular thiols other than glutathione in T cell apoptosis. J. Immunol. 154: 3194–3203

Ueda S, Nakamura H, Masutani H, Sasada T, Yonehara S, Takabayashi A, Yamaoka Y and Yodoi J (1998) Redox regulation of caspase-3(-like) protease activity: regulatory roles of thioredoxin and cytochrome c. J. Immunol. 161: 6689–6695

Hampton MB and Orrenius S (1997) Dual regulation of caspase activity by hydrogen peroxide: implications for apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 414: 552–556

Ueda S, Masutani H, Nakamura H, Tanaka T, Ueno M and Yodoi J (2002) Redox control of cell death. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 4: 405–414

Green DR and Kroemer G (2004) The pathophysiology of mitochondrial cell death. Science 305: 626–629

Vieira HL, Haouzi D, El Hamel C, Jacotot E, Belzacq AS, Brenner C and Kroemer G (2000) Permeabilization of the mitochondrial inner membrane during apoptosis: impact of the adenine nucleotide translocator. Cell Death Differ. 7: 1146–1154

Costantini P, Belzacq AS, Vieira HL, Larochette N, de Pablo MA, Zamzami N, Susin SA, Brenner C and Kroemer G (2000) Oxidation of a critical thiol residue of the adenine nucleotide translocator enforces Bcl-2-independent permeability transition pore opening and apoptosis. Oncogene 19: 307–314

Fujii J and Ikeda Y (2002) Advances in our understanding of peroxiredoxin, a multifunctional, mammalian redox protein. Redox Rep. 7: 123–130

Zhou Y, Kok KH, Chun AC, Wong CM, Wu HW, Lin MC, Fung PC, Kung H and Jin DY (2000) Mouse peroxiredoxin V is a thioredoxin peroxidase that inhibits p53-induced apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 268: 921–927

Kim H, Lee TH, Park ES, Suh JM, Park SJ, Chung HK, Kwon OY, Kim YK, Ro HK and Shong M (2000) Role of peroxiredoxins in regulating intracellular hydrogen peroxide and hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis in thyroid cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 18266–18270

Park SH, Chung YM, Lee YS, Kim HJ, Kim JS, Chae HZ and Yoo YD (2000) Antisense of human peroxiredoxin II enhances radiation-induced cell death. Clin. Cancer Res. 6: 4915–4920

Neumann CA, Krause DS, Carman CV, Das S, Dubey DP, Abraham JL, Bronson RT, Fujiwara Y, Orkin SH and Van Etten RA (2003) Essential role for the peroxiredoxin Prdx1 in erythrocyte antioxidant defence and tumour suppression. Nature 424: 561–565

Lee TH, Kim SU, Yu SL, Kim SH, Park do S, Moon HB, Dho SH, Kwon KS, Kwon HJ, Han YH, Jeong S, Kang SW, Shin HS, Lee KK, Rhee SG and Yu DY (2003) Peroxiredoxin II is essential for sustaining life span of erythrocytes in mice. Blood 101: 5033–5038

Green DR and Reed JC (1998) Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science 281: 1309–1312

Liu X, Kim CN, Yang J, Jemmerson R and Wang X (1996) Induction of apoptotic program in cell-free extracts: requirement for dATP and cytochrome c. Cell 86: 147–157

Susin SA, Lorenzo HK, Zamzami N, Marzo I, Snow BE, Brothers GM, Mangion J, Jacotot E, Costantini P, Loeffler M, Larochette N, Goodlett DR, Aebersold R, Siderovski DP, Penninger JM and Kroemer G (1999) Molecular characterization of mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor. Nature 397: 441–446

Konishi A, Shimizu S, Hirota J, Takao T, Fan Y, Matsuoka Y, Zhang L, Yoneda Y, Fujii Y, Skoultchi AI and Tsujimoto Y (2003) Involvement of histone H1.2 in apoptosis induced by DNA double-strand breaks. Cell 114: 673–688

Du C, Fang M, Li Y, Li L and Wang X (2000) Smac, a mitochondrial protein that promotes cytochrome c-dependent caspase activation by eliminating IAP inhibition. Cell 102: 33–42

Verhagen AM, Ekert PG, Pakusch M, Silke J, Connolly LM, Reid GE, Moritz RL, Simpson RJ and Vaux DL (2000) Identification of DIABLO, a mammalian protein that promotes apoptosis by binding to and antagonizing IAP proteins. Cell 102: 43–53

Suzuki Y, Imai Y, Nakayama H, Takahashi K, Takio K and Takahashi R (2001) A serine protease, HtrA2, is released from the mitochondria and interacts with XIAP, inducing cell death. Mol. Cell 8: 613–621

Spyrou G, Enmark E, Miranda VA and Gustafsson J (1997) Cloning and expression of a novel mammalian thioredoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 2936–2941

Tanaka T, Hosoi F, Yamaguchi-Iwai Y, Nakamura H, Masutani H, Ueda S, Nishiyama A, Takeda S, Wada H, Spyrou G and Yodoi J (2002) Thioredoxin-2 (TRX-2) is an essential gene regulating mitochondria-dependent apoptosis. EMBO J. 21: 1695–1703

Gasdaska PY, Berggren MM, Berry MJ and Powis G (1999) Cloning, sequencing and functional expression of a novel human thioredoxin reductase. FEBS Lett. 442: 105–111

Miranda-Vizuete A, Damdimopoulos AE, Pedrajas JR, Gustafsson JA and Spyrou G (1999) Human mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase cDNA cloning, expression and genomic organization. Eur. J. Biochem. 261: 405–412

Lee SR, Kim JR, Kwon KS, Yoon HW, Levine RL, Ginsburg A, Rhee SG, Watabe S, Hiroi T, Yamamoto Y, Fujioka Y, Hasegawa H, Yago N and Takahashi SY (1999) Molecular cloning and characterization of a mitochondrial selenocysteine-containing thioredoxin reductase from rat liver. SP-22 is a thioredoxin-dependent peroxide reductase in mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 4722–4734

Sun QA, Kirnarsky L, Sherman S and Gladyshev VN (2001) Selenoprotein oxidoreductase with specificity for thioredoxin and glutathione systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 3673–3678

Damdimopoulos AE, Miranda-Vizuete A, Pelto-Huikko M, Gustafsson JA and Spyrou G (2002) Human mitochondrial thioredoxin. Involvement in mitochondrial membrane potential and cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 33249–33257

Nonn L, Williams RR, Erickson RP and Powis G (2003) The absence of mitochondrial thioredoxin 2 causes massive apoptosis, exencephaly, and early embryonic lethality in homozygous mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 916–922

Conrad M, Jakupoglu C, Moreno SG, Lippl S, Banjac A, Schneider M, Beck H, Hatzopoulos AK, Just U, Sinowatz F, Schmahl W, Chien KR, Wurst W, Bornkamm GW and Brielmeier M (2004) Essential role for mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase in hematopoiesis, heart development, and heart function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24: 9414–9423

Loeffler M, Daugas E, Susin SA, Zamzami N, Metivier D, Nieminen AL, Brothers G, Penninger JM and Kroemer G (2001) Dominant cell death induction by extramitochondrially targeted apoptosis-inducing factor. FASEB J. 15: 758–767

Ichijo H, Nishida E, Irie K, ten Dijke P, Saitoh M, Moriguchi T, Takagi M, Matsumoto K, Miyazono K and Gotoh Y (1997) Induction of apoptosis by ASK1, a mammalian MAPKKK that activates SAPK/JNK and p38 signaling pathways. Science 275: 90–94

Saito M, Nishitoh H, Fujii M, Takeda K, Tobiume K, Sawada Y, Kawabata M, Miyazono K and Ichijyo H (1998) Mammalian thioredoxin is a direct inhibitor of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase (ASK) 1. EMBO J. 17: 2596–2606

Chen Z, Seimiya H, Naito M, Mashima T, Kizaki A, Dan S, Imaizumi M, Ichijo H, Miyazono K and Tsuruo T (1999) ASK1 mediates apoptotic cell death induced by genotoxic stress. Oncogene 18: 173–180

Hatai T, Matsuzawa A, Inoshita S, Mochida Y, Kuroda T, Sakamaki K, Kuida K, Yonehara S, Ichijo H and Takeda K (2000) Execution of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1)-induced apoptosis by the mitochondria-dependent caspase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 26576–26581

Nakagawa T, Zhu H, Morishima N, Li E, Xu J, Yankner BA and Yuan J (2000) Caspase-12 mediates endoplasmic-reticulum-specific apoptosis and cytotoxicity by amyloid-beta. Nature 403: 98–103

Nishitoh H, Matsuzawa A, Tobiume K, Saegusa K, Takeda K, Inoue K, Hori S, Kakizuka A and Ichijo H (2002) ASK1 is essential for endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced neuronal cell death triggered by expanded polyglutamine repeats. Genes Dev. 16: 1345–1355

Wei MC, Zong WX, Cheng EH, Lindsten T, Panoutsakopoulou V, Ross AJ, Roth KA, MacGregor GR, Thompson CB and Korsmeyer SJ (2001) Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science 292: 727–730

Urano F, Wang X, Bertolotti A, Zhang Y, Chung P, Harding HP and Ron D (2000) Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science 287: 664–666

Kadowaki H, Nishitoh H, Urano F, Sadamitsu C, Matsuzawa A, Takeda K, Masutani H, Yodoi J, Urano Y, Nagano T and Ichijo H (2005) Amyloid-beta induces neuronal cell death through ROS-mediated ASK-1 activation. Cell Death Differ. 12: 19–24

Matsuo Y, Akiyama N, Nakamura H, Yodoi J, Noda M and Kizaka-Kondoh S (2001) Identification of a novel thioredoxin-related transmembrane protein. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 10032–10038

Matsuo Y, Nishinaka Y, Suzuki S, Kojima M, Kizaka-Kondoh S, Kondo N, Son A, Sakakura-Nishiyama J, Yamaguchi Y, Masutani H, Ishii Y and Yodoi J (2004) TMX, a human transmembrane oxidoreductase of the thioredoxin family: the possible role in disulfide-linked protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 423: 81–87

Yodoi J, Takatsuki K and Masuda T (1974) Letter: two cases of T-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia in Japan. N. Engl. J. Med. 290: 572–573

Poiesz BJ, Ruscetti FW, Gazdar AF, Bunn PA, Minna JD and Gallo RC (1980) Detection and isolation of type C retrovirus particles from fresh and cultured lymphocytes of a patient with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77: 7415–7419

Miyoshi I, Kubonishi I, Yoshimoto S, Akagi T, Ohtsuki Y, Shiraishi Y, Nagata K and Hinuma Y (1981) Type C virus particles in a cord T-cell line derived by co-cultivating normal human cord leukocytes and human leukaemic T cells. Nature 294: 770–771

Uchiyama T, Yodoi J, Sagawa K, Takatsuki K and Uchino H (1977) Adult T-cell leukemia: clinical and hematologic features of 16 cases. Blood 50: 481–492

Uchiyama T and Yodoi J (1995) Adult T Cell Leukemia and Related Diseases (Austin: R. G. Landes company) pp. 1–139

Yodoi J and Uchiyama T (1992) Diseases associated with HTLV-I: virus, IL-2 receptor dysregulation and redox regulation. Immunol. Today 13: 405–411

Jeang KT, Giam CZ, Majone F and Aboud M (2004) Life, death, and tax: role of HTLV-I oncoprotein in genetic instability and cellular transformation. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 31991–31994

Yoshida M (2001) Multiple viral strategies of HTLV-1 for dysregulation of cell growth control. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19: 475–496

Matsuoka M (2003) Human T-cell leukemia virus type I and adult T-cell leukemia. Oncogene 22: 5131–5140

Georges SA, Giebler HA, Cole PA, Luger K, Laybourn PJ and Nyborg JK (2003) Tax recruitment of CBP/p300, via the KIX domain, reveals a potent requirement for acetyltransferase activity that is chromatin dependent and histone tail independent. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 3392–3404

Tagaya Y, Maeda Y, Mitsui A, Kondo N, Matsui H, Hamuro J, Brown N, Arai K, Yokota T, Wakasugi H and Yodoi J (1989) ATL-derived factor (ADF), an IL-2 receptor/Tac inducer homologous to thioredoxin; possible involvement of dithiol-reduction in the IL-2 receptor induction. EMBO J. 8: 757–764

Yodoi J and Tursz T (1991) ADF, a growth-promoting factor derived from adult T cell leukemia and homologous to thioredoxin: involvement in lymphocyte immortalization by HTLV-I and EBV. Adv. Cancer Res. 57: 381–411

Makino S, Masutani H, Maekawa N, Konishi I, Fujii S, Yamamoto R and Yodoi J (1992) Adult T-cell leukaemia-derived factor/thioredoxin expression on the HTLV-I transformed T-cell lines: heterogeneous expression in ALT-2 cells. Immunology 76: 578–583

Masutani H, Hirota K, Sasada T, Ueda TY, Taniguchi Y, Sono H and Yodoi J (1996) Transactivation of an inducible anti-oxidative stress protein, human thioredoxin by HTLV-I Tax. Immunol. Lett. 54: 67–71

Nishiyama A, Matsui M, Iwata S, Hirota K, Masutani H, Nakamura H, Takagi Y, Sono H, Gon Y and Yodoi J (1999) Identification of thioredoxin-binding protein-2/vitamin D(3) up-regulated protein 1 as a negative regulator of thioredoxin function and expression. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 21645–21650

Chen KS and DeLuca HF (1994) Isolation and characterization of a novel cDNA from HL-60 cells treated with 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-3. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1219: 26–32

Junn E, Han SH, Im JY, Yang Y, Cho EW, Um HD, Kim DK, Lee KW, Han PL, Rhee SG and Choi I (2000) Vitamin D3 up-regulated protein 1 mediates oxidative stress via suppressing the thioredoxin function. J. Immunol. 164: 6287–6295

Yamanaka H, Maehira F, Oshiro M, Asato T, Yanagawa Y, Takei H and Nakashima Y (2000) A possible interaction of thioredoxin with VDUP1 in HeLa cells detected in a yeast two-hybrid system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 271: 796–800

Butler LM, Zhou X, Xu WS, Scher HI, Rifkind RA, Marks PA and Richon VM (2002) The histone deacetylase inhibitor SAHA arrests cancer cell growth, up-regulates thioredoxin-binding protein-2, and down-regulates thioredoxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 11700–11705

Schulze PC, De Keulenaer GW, Yoshioka J, Kassik KA and Lee RT (2002) Vitamin D3-upregulated protein-1 (VDUP-1) regulates redox-dependent vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation through interaction with thioredoxin. Circ. Res. 91: 689–695

Han SH, Jeon JH, Ju HR, Jung U, Kim KY, Yoo HS, Lee YH, Song KS, Hwang HM, Na YS, Yang Y, Lee KN and Choi I (2003) VDUP1 upregulated by TGF-beta1 and 1,25-dihydorxyvitamin D3 inhibits tumor cell growth by blocking cell-cycle progression. Oncogene 22: 4035–4046

Joguchi A, Otsuka I, Minagawa S, Suzuki T, Fujii M and Ayusawa D (2002) Overexpression of VDUP1 mRNA sensitizes HeLa cells to paraquat. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 293: 293–297

Nishinaka Y, Nishiyama A, Masutani H, Oka S, Ahsan KM, Nakayama Y, Ishii Y, Nakamura H, Maeda M and Yodoi J (2004) Loss of thioredoxin-binding protein-2/vitamin D3 up-regulated protein 1 in human T-cell leukemia virus type I-dependent T-cell transformation: implications for adult T-cell leukemia leukemogenesis. Cancer Res. 64: 1287–1292

Nishinaka Y, Masutani H, Oka S, Matsuo Y, Yamaguchi Y, Nishio K, Ishii Y and Yodoi J (2004) Importin alpha1 (Rch1) mediates nuclear translocation of thioredoxin-binding protein-2/vitamin D(3)-up-regulated protein 1. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 37559–37565

Ikarashi M, Takahashi Y, Ishii Y, Nagata T, Asai S and Ishikawa K (2002) Vitamin D3 up-regulated protein 1 (VDUP1) expression in gastrointestinal cancer and its relation to stage of disease. Anticancer Res. 22: 4045–4048

Goldberg SF, Miele ME, Hatta N, Takata M, Paquette-Straub C, Freedman LP and Welch DR (2003) Melanoma metastasis suppression by chromosome 6: evidence for a pathway regulated by CRSP3 and TXNIP. Cancer Res. 63: 432–440

Maeda M, Arima N, Daitoku Y, Kashihara M, Okamoto H, Uchiyama T, Shirono K, Matsuoka M, Hattori T and Takatsuki K (1987) Evidence for the interleukin-2 dependent expansion of leukemic cells in adult T cell leukemia. Blood 70: 1407–1411

Ameisen JC (1994) Programmed cell death (apoptosis) and cell survival regulation: relevance to AIDS and cancer. AIDS 8: 1197–1213

Gougeon ML (2003) Apoptosis as an HIV strategy to escape immune attack. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3: 392–404

Masutani H, Naito M, Takahashi K, Hattori T, Koito A, Maeda Y, Takatsuki K, Go T, Nakamura H, Fujii S, Yoshida Y, Okuma M and Yodoi J (1992) Dysregulation of adult T cell leukemia derived factor (ADF)/human thioredoxin in HIV infection: loss of ADF high producer cells in lymphoid tissues of AIDS patients. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 8: 1707–1715

Aillet F, Masutani H, Elbim C, Raoul H, Chene L, Nugeyre MT, Paya C, Barre Sinoussi F, Gougerot Pocidalo MA and Israel N (1998) Human immunodeficiency virus induces a dual regulation of Bcl-2, resulting in persistent infection of CD4(+) T- or monocytic cell lines. J. Virol. 72: 9698–9705

Elbim C, Pillet S, Prevost MH, Preira A, Girard PM, Rogine N, Masutani H, and Hakim J, Israel N and Gougerot-Pocidalo MA (1999) Redox and activation status of monocytes from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: relationship with viral load. J. Virol. 73: 4561–4566

Geiben-Lynn R, Kursar M, Brown NV, Addo MM, Shau H, Lieberman J, Luster AD and Walker BD (2003) HIV-1 antiviral activity of recombinant natural killer cell enhancing factors, NKEF-A and NKEF-B, members of the peroxiredoxin family. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 1569–1574

Jin DY, Chae HZ, Rhee SG and Jeang KT (1997) Regulatory role for a novel human thioredoxin peroxidase in NF-kappaB activation. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 30952–30961

Nakamura H, De Rosa S, Roederer M, Anderson MT, Dubs JG, Yodoi J, Holmgren A, Herzenberg LA and Herzenberg LA (1996) Elevation of plasma thioredoxin levels in HIV-infected individuals. Int. Immunol. 8: 603–611

Nakamura H, Herzenberg LA, Bai J, Araya S, Kondo N, Nishinaka Y and Yodoi J (2001) Circulating thioredoxin suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced neutrophil chemotaxis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 15143–15148

Davis DA, Newcomb FM, Starke DW, Ott DE, Mieyal JJ and Yarchoan R (1997) Thioltransferase (glutaredoxin) is detected within HIV-1 and can regulate the activity of glutathionylated HIV-1 protease in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 25935–25940

Davis DA, Yusa K, Gillim LA, Newcomb FM, Mitsuya H and Yarchoan R (1999) Conserved cysteines of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease are involved in regulation of polyprotein processing and viral maturation of immature virions. J. Virol. 73: 1156–1164

Davis DA, Brown CA, Newcomb FM, Boja ES, Fales HM, Kaufman J, Stahl SJ, Wingfield P and Yarchoan R (2003) Reversible oxidative modification as a mechanism for regulating retroviral protease dimerization and activation. J. Virol. 77: 3319–3325

Matthias LJ, Yam PT, Jiang XM, Vandegraaff N, Li P, Poumbourios P, Donoghue N and Hogg PJ (2002) Disulfide exchange in domain 2 of CD4 is required for entry of HIV-1. Nat. Immunol. 3: 727–732

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the laboratory for helpful discussions, Ms. Akie Teratani for graphic artwork, and Ms. Y Kanekiyo for secretarial help. This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan and a grant-in-aid from the Research and Development Program for New Bio-industry Initiatives.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Edited by G Kroemer

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Masutani, H., Ueda, S. & Yodoi, J. The thioredoxin system in retroviral infection and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 12 (Suppl 1), 991–998 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cdd.4401625

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cdd.4401625

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

TXNIP: A key protein in the cellular stress response pathway and a potential therapeutic target

Experimental & Molecular Medicine (2023)

-

Tremella fuciformis polysaccharides alleviates UV-provoked skin cell damage via regulation of thioredoxin interacting protein and thioredoxin reductase 2

Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences (2023)

-

Glutathione reductase system changes in HTLV-1 infected patients

VirusDisease (2022)

-

Targeting the NF-E2-Related Factor 2 Pathway: a Novel Strategy for Traumatic Brain Injury

Molecular Neurobiology (2018)

-

The sense behind retroviral anti-sense transcription

Virology Journal (2017)