Abstract

The purpose of this study is to present the first report of a case of primary frosted branch angiitis from the UK and to review the characteristics of this rare disease. Primary frosted branch angiitis causes characteristic florid translucent retinal perivascular sheathing of both arterioles and venules in association with variable uveitis, retinal oedema and visual loss, normally with good recovery. A total of 57 cases have been reported in the world literature. Atypical, typically focal frosted branch angiitis may also occur secondary to other causes of intraocular inflammation, especially cytomegalovirus retinitis. Primary frosted branch angiitis has a characteristic presentation but a variable course, typically affecting children or young adults. The disease is likely to represent a common immune pathway in response to multiple infective agents. The optimal treatment is unclear.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Case report

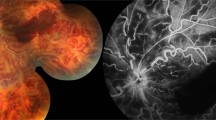

A 7-year-old boy presented after 3 days of blurred vision and floaters in both eyes, preceded by an upper respiratory tract infection treated with oral amoxycillin. There was no other significant medical history. On examination, visual acuities were right 6/60 and left 2/36. There was a mild right relative afferent pupillary defect. There was bilateral diffuse conjunctival injection with mild nongranulomatous anterior uveitis and vitritis. Intraocular pressures were right 12 mmHg and left 8 mmHg. Fundal examination (Figure 1) revealed symmetrical widespread retinal vasculitis, including prominent sheathing affecting both venules and arterioles. There was bilateral moderate papillitis, severe macular oedema, and scattered small retinal haemorrhages. The patient had submandibular lymphadenopathy, but no other abnormality on general examination.

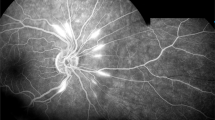

Full blood count and differential cell count were normal, as were erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, chest X-ray, angiotensin-converting enzyme, immunoglobulins, and liver function tests. There was no evidence of cellular or humoral immune deficiency. An auto-antibody screen was negative, as was the Paul Bunnell test. Serology for cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex, varicella zoster and Epstein–Barr viruses, rubella, and syphilis were negative. Fluorescein angiography (FA, Figure 2) revealed normal blood flow, but late diffuse staining and leakage of the affected vessels and the optic discs. A diagnosis of primary frosted branch angiitis (FBA) was made. Within 24 h visual acuity had deteriorated to counting fingers at 1 m in both eyes. He was treated with oral prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day, with topical steroid and mydriatic. Response was rapid, with resolution of all clinical signs and improvement in visual acuity to 6/9 in both eyes, by day 15. Systemic steroid treatment was tapered and discontinued after 4 weeks.

After 4 weeks, uveitis with mild macular oedema recurred, without angiitis. Topical steroid was recommenced. An MRI scan of orbits and brain was normal, as was electrophysiology. The Goldmann fields showed generalised constriction. The disease course fluctuated in the early stages, accompanied by an inferior punctate retinitis, but subsided 14 months later, leaving fine retinal pigment epithelial changes at both maculae, but visual acuity of better than 6/6 in both eyes.

Discussion and review of the literature

In 1976 Ito1 reported a 6-year-old Japanese boy with panuveitis and widespread retinal vasculitis. The florid translucent perivascular exudate inspired the descriptive term ‘frosted branch angiitis’. The phenomenon is rare and probably a new entity, only 57 cases2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46 having been recorded in the world literature (Table 1). The great majority (75%) of patients are Japanese; indeed, it was not until 198813 that any patient outside Japan was reported. A total of 9 cases have subsequently been reported from the USA13,25,27,32,44 and single cases from Turkey,37 Korea,40 India,41 and Spain.46 Our patient is the first to be described in the UK.

FBA predominantly affects the young and fit. There appears to be a bimodal age distribution (Figure 3), with one peak in childhood and a second in the third decade. The youngest patient reported to date was 2 years16 and the oldest 42 years.28 There has been a preponderance of females (61%) to males (39%).

The most common presenting symptoms of FBA are subacute visual loss, floaters or photopsiae. The visual acuity may be substantially reduced (Table 1), even to perception of light.4,17 Most patients (75%) have bilateral disease.

Typical FBA has a striking fundal appearance (Figures 1 and 2); the retinal vasculitis is widespread and bilateral with a ‘frosted’ quality to the perivascular exudate. Mild-to moderate iritis with vitritis is common, as is retinal oedema. Intraretinal haemorrhages and punctate hard exudates are only occasionally seen. Papillitis, if present, is usually mild; marked disc oedema has been noted only by us. FA is near normal in the early phase, but there is late leakage from the larger affected retinal vessels. In the recovery phase, microaneurysms have been described.3 The vasculitis is usually nonocclusive. Visual field analysis reveals constriction or relative central defects that improve after clinical resolution1.6,7,9,10,19,20,36,37,41,43 The latter are thought to result from macular oedema.9,37

Electrophysiology has shown a reduction in the amplitudes of the electroretinogram (ERG), electro-oculogram (EOG), and visually evoked response (VER). This would be consistent with a widespread dysfunction of the retina, pigment epithelium, and optic nerve.9,47 The EOG and VER may return to normal,1,4,9 but the ERG changes have generally persisted beyond convalescence, suggesting permanent retinal damage.

Most patients with FBA have been treated with systemic steroids and have rapidly resolved with good visual recovery (Table 1). Less frequently, recovery has taken place over many months. Aciclovir has been used11,17,21,23,24,26,40 with unknown effect. Recurrence is rare.4,48

The prognosis in FBA has not always been favourable. Macular scarring has severely limited vision in 3 patients.13,25,37 Complications include retinal vein13,49 or artery occlusion,24 macular epiretinal membrane formation,38 diffuse retinal fibrosis,37 retinal tear formation,13 vitreous haemorrhage,50 optic disc atrophy1 and peripheral atrophic retinal lesions.1,9,16,30,37 The final visual acuity has been 6/60 or worse in 10% of affected eyes thus far reported (cases 1, 14, 34, 42, 46, 48, 52, 55, 56, Table 1), nine of which received systemic steroid treatment. In contrast, five patients (eight affected eyes) with severe visual loss (cases 7,23,24,32,37, Table 1) did not receive systemic steroid treatment, yet regained high acuity.

The cause of FBA is unknown. The typical onset of FBA after a multifactorial prodromal illness has led to the suggestion of a hypersensitivity reaction to various infective agents,23 which may initiate FBA via a common pathway, possibly of immune-complex deposition.13,38 This would support the use of systemic corticosteroids for those with substantial visual loss. However, the visual results with or without systemic steroid treatment thus far provide no clear guidance on treatment.

Other causes of retinal vasculitis should be excluded, especially viral retinitis, sarcoidosis, multiple sclerosis, toxoplasmosis, syphilis, and Behçet's disease. Infiltrative causes such as lymphoma and leukaemia may occasionally mimic FBA. However, the distinctive clinical appearance is usually pathognomonic. Tentative suggestions31 of a link to HLA-A2 are inadequately supported. A presumed viral illness has preceded the onset in 33% of cases including our own.2,3,4,5,7,13,17,19,22,23,25,27,29,31,35,39,41,42 No consistent aetiological agent has been identified, but positive serology results have been reported for: herpes simplex virus (HSV),11,13,26,34,35,41 varicella zoster virus (VZV),2,5,11,13,21 tuberculoprotein,1,5,34 antistreptolysin O,4,13,39 Epstein-Barr virus,25 CMV,34 Coxsackie virus A10,31 adenovirus,34 measles34 and rubella.41

The cases listed in Table 1 and referred to above appear, with limited variation, to adhere to Ito's original description of a primary idiopathic FBA. However, other cases of FBA, often localised, have been described, which appear either to be secondary to intraocular infection by CMV,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58 HSV (confirmed by aqueous PCR),59,60 herpesvirus hominis,61 toxoplasmosis62 or Fusarium dimerium,63 or in association with systemic lupus erythematosus,64 Crohn's disease,65 lymphoma,66 leukaemia67 and Behçet's disease (our own unpublished case, Figure 4).

In summary, Frosted branch angiitis in typical form, unassociated with preexisting intraocular inflammation, is likely to be a primary immunological process in response to a number of provoking antigens. As discussed by Kleiner,13,68 an apparently different form exists, which is secondary to concurrent inflammation, most commonly in association with CMV retinitis.51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58 Kleiner classifies the form seen in association with intraocular lymphoma or leukaemia differently, which may mimic FBA but is probably an infiltrative process. Our review of the world literature to date suggests that this proposal is sound. However, in order to distinguish classical FBA, as originally described by Ito1 from secondary forms and masquerades, we propose the descriptive term ‘primary idiopathic frosted branch angiitis’.

References

Ito Y, Nakano M, Kyu N, Takeuchi M . Frosted branch angiitis in a child. Rinsho Ganka (Jpn J Clin Ophthalmol) 1976; 30: 797–803.

Miyazaki H, Kitahara K, Anazawa K, Noji J, Yamaguchi M, Imai Y . A case of retinal vasculitis and uveitis as the complications of chicken pox. Ganka (Ophthalmology) 1982; 24: 1451–1454.

Sakanishi Y, Kanagami S, Ohara K . A case of uveitis with so-called frosted branch retinal angiitis in a child. Rinsho Ganka (Jpn J Clin Ophthalmol) 1984; 38: 803–807.

Higuchi K, Maeda K, Uji T, Yokoyama M . A case of acute uveitis in a child with frosted branch retinal angiitis. Ganka Rinsho Iho (Jpn Rev Clin Ophthalmol) 1985; 79: 2660–2664.

Yamane S, Nishiuchi T, Nakagawa Y, Iwase T, Hama M . A case of frosted-branch angiitis of the retina. Nihon Ganka Kiyo (Folia Ophthalmol Jpn) 1985; 36: 1822–1825.

Kadoya K, Obara Y, Chikuda M, Hashi H, Osawa M . A case of frosted-branch-angiitis in an adult. Nihon Ganka Kiyo (Folia Ophthalmol Jpn) 1986; 37: 1055–1059.

Horiuchi T . ‘Frosted branch retinal angiitis’ in an adult-A case and review. Atarashii Ganka (J Eye) 1987; 4: 273–278.

Ichikawa K, Majima A . A case of frosted branch angiitis (Abstract). Ganka Rinsho Iho (Jpn Rev Clin Ophthalmol) 1987; 81: 1749.

Watanabe Y, Takeda N, Adachi-Usami E . A case of frosted branch angiitis. Br J Ophthalmol 1987; 71: 553–558.

Kubota T, Kubota A, Koike N, Oba H . A case of uveitis with so-called frosted branch angiitis. Ganka Rinsho Iho (Jpn Rev Clin Ophthalmol) 1987; 81: 2465–2468.

Kodama Y, Masuyama Y, Kodama Y . A case of frosted branch angiitis of the retina. Nihon Ganka Kiyo (Folia Ophthalmol Jpn) 1988; 39: 491–497.

Suzuki K, Fujiwara T, Sato N, Yago K . A case of frosted-branch retinal angiitis. Nihon Ganka Kiyo (Folia Ophthalmol Jpn) 1988; 39: 674–677.

Kleiner RC, Kaplan HJ, Shakin JL, Yanuzzi, LA, Crosswell HH, McLean WC . Acute frosted retinal periphlebitis. Am J Ophthalmol 1988; 106: 27–34.

Asai H, Segawa Y, Mukai S, Shirao E . A case of frosted branch retinal angiitis (Abstract). Ganka Rinsho Iho (Jpn Rev Clin Ophthalmol) 1989; 83: 144.

Takaseki M, Shoda S, Ra K . Long-term follow-up in a case of uveitis in a child with frosted branch retinal angiitis. Ganka (Ophthalmology) 1989; 31: 763–768.

Hikichi T, Yoshida A, Nara Y . A case of frosted retinal periphlebitis in a 21/2-year-old girl. Nihon Ganka Kiyo (Folia Ophthalmol Jpn) 1989; 40: 1752–1755.

Kanai K, Nomura T, Fukuda S, Takahashi Y, Kogure M . An adult case of frosted branch angiitis. Ganka Rinsho Iho (Jpn Rev Clin Ophthalmol) 1989; 83: 1681–1683.

Kijosawa A, Takao Y, Hayashi H, Momoeda S, Oshima K, Ikui A . A case of frosted-branch angiitis in an adult. Nihon Ganka Kiyo (Folia Ophthalmol Jpn) 1989; 40: 2189–2193.

Terasaki H, Yanagida K, Tanaka T . An adult case of frosted branch angiitis with various systemic manifestations. Nihon Ganka Kiyo (Folia Ophthalmol Jpn) 1989; 40: 2438–2442.

Yoshida S, Kadoya K, Osawa M, Obara Y . Longterm followup in a case of frosted retinal vasculitis. Ganka Rinsho Iho (Jpn Rev Clin Ophthalmol) 1990; 84: 296–302.

Narita K, Sato A . Systemic acyclovir was effective in a case of recurrent retinal angiitis. Rinsho Ganka (Jpn J Clin Ophthalmol) 1990; 44: 739–743.

Isobe Y, Yamamoto T . Two juvenile cases of frosted-branch angiitis of the retina. Ganka Rinsho Iho (Jpn Rev Clin Ophthalmol) 1990; 84: 1507–1511.

Mizukami Y, Yagasaki T, Shimazu K, Yagasaki K . A 5-year-old girl with frosted branch angiitis of the retina. Nihon Ganka Kiyo (Folia Ophthalmol Jpn) 1990; 41: 2080–2087.

Emi K, Seki R, Oguro Y . A case of so-called frosted retinal angiitis with branch retinal artery occlusion. Nihon Ganka Kiyo (Folia Ophthalmol Jpn) 1991; 42: 134–139.

Sugin SL, Henderly DE, Friedman SM, Jampol LM, Doyle JW . Unilateral frosted branch angiitis. Am J Ophthalmol 1991; 111: 682–685.

Mikami Y, Takahira M, Suzuki T, Koshio A . Acyclovir was effective in a case of frosted retinal branch angiitis. Ganka Rinsho Iho (Jpn Rev Clin Ophthalmol) 1991; 85: 2050–2051.

Vander JF, Masciulli L . Unilateral frosted branch angiitis. Am J Ophthalmol 1991; 112: 477–478.

Ohta A, Oguro Y, Satoh K . Unilateral frosted branch retinal angiitis in an adult. Ganka Rinsho Iho (Jpn Rev Clin Ophthalmol) 1992; 86: 569–573.

Tsue Y, Maeda T . A case of unilateral frosted branch angiitis in an adult (Abstract). Ganka Rinsho Iho (Jpn Rev Clin Ophthalmol) 1992; 86: 718.

Suzuki H, Takeda M, Suzuki J . A case of frosted-branch retinal angiitis with bilateral serous retinal detachment. Rinsho Ganka (Jpn J Clin Ophthalmol) 1992; 46: 919–922.

Tachinami K, Katayama T, Takeda N, Kubota Y, Asaka N . Frosted branch angiitis in an adult. Ganka Rinsho Iho (Jpn Rev Clin Ophthalmol) 1992; 86: 1645–1649.

Hamed LM, Fang EN, Fanous MM, Mames R, Friedman S . Frosted branch angiitis: the role of systemic corticosteroids. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1992; 29: 312–313.

Browning DJ . Mild frosted branch periphlebitis. Am J Ophthalmol 1992; 114: 505–506.

Nakai A, Saika S . A case of frosted-branch retinal angiitis in a child. Ann Ophthalmol 1992; 24: 415–417.

Chuman H, Yamane I, Tahara H, Sugai S, Harada K . Frosted-branch retinal angiitis in a child. Ganka Rinsho Iho (Jpn Rev Clin Ophthalmol) 1993; 87: 327–331.

Uenoyama S, Osamu T, Saika S, Kobata S, Okada Y . Frosted branch angiitis in an adult. Ganka Rinsho Iho (Jpn Rev Clin Ophthalmol) 1993; 87: 756–760.

Atmaca LS, Gunduz K . Acute frosted retinal periphlebitis. Acta Ophthalmol 1993; 71: 856–859.

Okinami S, Nakamatsu T, Saito I, Oohira A, Yoshida M, Yamakawa R, Ishikawa M, Miyara N . Four cases of frosted retinal angiitis. Nihon Ganka Kiyo (Folia Ophthalmol Jpn) 1994; 45: 314–318.

Yamagata S, Kobayakawa N, Watanabe H, Matsuhashi M . Frosted branch angiitis with suspected streptococcal infection. Atarashii Ganka (J Eye) 1995; 12: 1317–1321.

Lee YM, Lim ST, Choi GJ, Lee MK . A case of frosted branch angiitis. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc 1995; 36: 1278–1282.

Biswas J, Fogla R, Madhaven HN . Bilateral frosted branch angiitis in an 8-year old Indian girl. Retina 1996; 16: 444–445.

Kawaguchi S, Yasuda F, Kawamura T, Hara J . A case of frosted branch angiitis. Nihon Ganka Kiyo (Folia Ophthalmol Jpn) 1996; 47: 1421–1425.

Masuda K, Ueno M, Watanabe I . A case of frosted branch angiitis with yellowish-white placoid lesions: fluorescein and indocyanine green angiography findings. Jpn J Ophthalmol 1998; 42: 484–489.

Borkowski LM, Jampol LM . Frosted branch angiitis complicated by retinal neovascularisation. Retina 1999; 19(5): 454–455.

Johkura K, Hara A, Hatton T, Hasegawa O, Kuroiwa Y . Frosted branch angiitis associated with aseptic meningitis. Eur J Neurol 2000; 7: 241.

Huerva V, Puig T, Sanchez MC, Jurjo C, Asenjo J . A new case of acute idiopathic frosted branch angiitis in Europe. Eyr J Ophthalmol 2002; 12: 127–130.

Kaburaki T, Nakamura M, Nagasawa K, Nagahara M, Joko S, Fujino Y . Two cases of frosted branch angiitis with central retinal vein occlusion. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2001; 45: 628–633.

Luo G, Yang P, Huang S, Jiang F, Wen F . A case of frosted branch angiitis and its visual electrophysiology. Doc Ophthalmol 1999; 97: 135–142.

Seo MS, Woo JM, Jeong SK, Park YG . Recurrent unilateral frosted branch angiitis. Jpn J Ophthalmol 1998; 42: 56–59.

Harigai R, Seki R, Emi K, Oguro Y, Sato Y . A case of frosted retinal angiitis associated with vitreous hemorrhage. Nihon Ganka Kiyo (Folia Ophthalmol Jpn) 1993; 44: 772–778.

Fine HF, Smith JA, Murante BL, Nussenblatt RB, Robinson MR . Frosted branch angiitis in a child with HIV infection. Am J Ophthalmol 2001; 131: 394–396.

Secchi AG, Tognon MS, Turrini B, Carniel G . Acute frosted retinal periphlebitis associated with cytomegalovirus retinitis. Retina 1992; 12: 245–247.

Cortina P, Diaz M, Espana E, Almenar L, Lopez-Aldeguer J . Acute frosted retinal periphlebitis associated with cytomegalovirus retinitis in a heart transplant patient. Retina 1994; 14: 463–464.

Greier SA, Nasemann J, Klauss V, Kronawitter U, Goebel FD . Frosted branch angiitis associated with cytomegalovirus retinitis. Am J Ophthalmol 1992; 113: 514–516.

Greier SA, Nasemann J, Klauss V, Kronawitter U, Goebel FD . Frosted branch angiitis in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1992; 113: 203–205.

Spaide RF, Vitale AT, Toth IR, Oliver JM . Frosted branch angiitis associated with cytomegalovirus retinitis. Am J Ophthalmol 1992; 113: 522–528.

Rabb MF, Jampol LM, Fish RH, Campo RV, Sobol WM, Becker NM . Retinal periphlebitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome with cytomegalovirus retinitis mimics acute frosted retinal periphlebitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1992; 110: 1257–1260.

Biswas J, Raizada S, Gopal L, Kumarasamy N, Solomon S . Bilateral frosted branch angiitis and cytomegalovirus retinitis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Indian J Ophthalmol 1999; 47: 195–197.

Chatzoulis DM, Theodosiadis PG, Apostolopoulos MN, Drakoulis N, Markomichelakis NN . Retinal perivasculitis in an immunocompetent patient with systemic herpes simplex infection. Am J Ophthalmol 1997; 123: 699–702.

Markomichelakis NN, Barampouti F, Zafirakis P, Chalkiadakis I, Kouris T, Ekonomopoulos N . Retinal vasculitis with a frosted branch angiitis-like response due to herpes simplex virus type 2. Retina 1999; 19(5): 455–457.

Savir H, Grosswasser Z, Menddelson, L . Herpes virus hominis encephalomyelitis and retinal vasculitis in adults. Ann Ophthalmol 1980; 12: 1369.

Ysasaga JE, Davies J . Frosted branch angiitis with ocular toxoplasmosis. Arch Ophthalmol 1999; 117: 1260–1261.

Gabriele P, Hutchins RK . Fusarium endophthalmitis in an intravenous drug abuser. Am J Ophthalmol 1996; 122: 119–121.

Quillen DA, Stathopoulos NA, Blankenship GW, Ferriss JA . Lupus associated frosted branch periphlebitis and exudative maculopathy. Retina 1997; 17: 449–451.

Sykes SO, Horton JC . Steroid-responsive retinal vasculitis with a frosted branch appearance in Crohn's disease. Retina 1997; 17: 451–454.

Ridley ME, McDonald R, Sternberg P, Blumenkranz MS, Zarbin MA, Schachat AP . Retinal manifestations of ocular lymphoma (reticulum cell sarcoma). Ophthalmology 1992; 99: 1153–1161.

Kim TS, Duker JS, Hedges TR . Retinal angiopathy resembling unilateral frosted branch angiitis in a patient with relapsing acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Am J Ophthalmol 1994; 117: 806–808.

Kleiner RC . Frosted branch angiitis: clinical syndrome or clinical sign?(Editorial). Retina 1997; 17: 370–372.

Acknowledgements

The authors have no financial or other interest in any proprietary product or medication discussed in this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Walker, S., Iguchi, A. & Jones, N. Frosted branch angiitis: a review. Eye 18, 527–533 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700712

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700712

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Combined central retinal vein occlusion and cilioretinal artery occlusion as the initial presentation of frosted branch angiitis: a case report and literature review

Journal of Ophthalmic Inflammation and Infection (2023)

-

Frosted-Branch-Angiitis als erstes Zeichen eines Morbus Behçet

Die Ophthalmologie (2023)

-

Frosted branch angiitis presenting after a SARS-CoV-2 infection

Journal of Ophthalmic Inflammation and Infection (2022)

-

Frosted-Branch-Angiitis – seltene Differenzialdiagnose einer retinalen Vaskulitis

Die Ophthalmologie (2022)

-

Unilateral frosted branch angiitis in an human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient with concurrent COVID-19 infection: a case report

Journal of Medical Case Reports (2021)