Abstract

Purpose To describe the results of 125I plaque brachytherapy of uveal melanomas anterior to the equator in terms of local control and the associated complications while trying to identify their risk factors (patients' demographic data, ocular, and tumour characteristics).

Methods Retrospective analysis of a series of patients treated by 125I between 1990 and 2000 in a single institution. The main outcome measures are evaluation of local tumour control and complications associated with 125I plaque brachytherapy of these melanomas.

Results During the study period, 136 patients were treated for an anterior tumour. The median follow-up was 62 months. The overall 5-year survival rate was 88.3%, the 5-year metastasis rate was 4% and the local recurrence rate was 1.5%. The mean final visual acuity was 20/40. The ocular complications most frequently observed at 5 years were cataract (50.3%), maculopathy (18.3%), intraocular inflammation (19.3%), and glaucoma (10.6%). Optic neuropathy, retinal detachment, keratitis, and intravitreous haemorrhage were also described. Risk factors for worse survival were age greater than 65 years and initial tumour thickness greater than 4 mm. Risk factors for the development of cataract were age more than 65 years old, male gender, and tumour diameter of more than 10 mm. Risk factors for intraocular inflammation were tumour thickness of more than 4 mm and invasion of the ciliary body.

Conclusions The use of 125I plaque brachytherapy to treat melanomas situated anterior to the equator allows good local and systemic control with a low rate of macular and optic disc complications. The most frequent complication was cataract formation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It seems now clearly established that the treatment modality used for choroidal melanoma (enucleation or 125I brachytherapy) does not affect the short-term overall survival.1 Radiotherapy is one of the various treatment options for small- to medium-sized choroidal melanomas and allows preservation of the eye and a certain residual visual function, particularly when irradiation spares the macula and optic disc. Brachytherapy is one of the irradiation techniques that can be used for the treatment of choroidal melanoma. The radioisotopes most frequently used are 125I and ruthenium 106.

Most published series on 125I plaque brachytherapy report the results of treatment without always taking into account the site of the tumour in relation to the equator2, 3 or by providing more detailed results for the treatment of posterior lesions due to the high rate of macular and optic disc complications.4, 5 We decided to analyse the results of 125I plaque brachytherapy on a large patient series, when this technique was used for the treatment of choroidal or ciliochoroidal melanoma situated anterior to the equator.

Materials and methods

This retrospective study reviewed patients treated by 125I plaque brachytherapy for uveal melanoma anterior to the equator, between January 1990 and December 2000 in a single institution. Patients with iris melanoma, hepatic metastases at the time of diagnosis and patients treated for relapse of a previously treated lesion were excluded.

Patients

All of the patients included had a complete clinical ophthalmologic assessment and B-mode ultrasound examination to measure tumour thickness at the time of the diagnosis, and fluorescein angiography was performed in some patients. The choice of treatment between 125I plaque brachytherapy and proton beam therapy in our institution depended on the size and site of the tumour. Brachytherapy is used for tumours whose posterior margin is anterior to the equator and of 18 mm or less in largest diameter. Posterior tumours are usually treated by proton beam. A general assessment with hepatic ultrasonography and chest X-ray looking for metastatic diseases was performed in every case. Data concerning demographic (patient's age, gender) ocular (side, iris colour, and visual acuity) and initial tumour characteristics (tumour diameter, thickness, presence of retinal detachment, or a lesion involving the ciliary body) were collected for all patients.

125I plaque brachytherapy

125I plaques were inserted under local or general anaesthesia. After disinsertion of the conjunctiva, the oculomotor muscles were retracted with silk stay sutures and the tumour was visualised by transillumination. The base of the tumour was covered by the plaque, whose diameter was calculated in order to cover the tumour with a circumferential safety margin of 2 mm. Plaques with a diameter of 12, 14, 16, 18, or 20 mm were available. The application time was calculated to deliver a total dose of 90 Gy to the tumour apex. This time varies as a function of tumour thickness, plaque diameter, and iodine grain radioactivity. For all lesions less than 5 mm thick, the dose was calculated to deliver 90 Gy at 5 mm, due to the error associated with dosimetric estimations for treatment depths less than 5 mm. The plaque was left in place for the duration determined by preoperative dosimetry and was then removed under local anaesthesia.

Follow-up

Follow-up comprised ophthalmologic examination 1 month after irradiation, then every 6 months in our institute, with an intermediate examination performed by the local ophthalmologist. A functional assessment was performed annually (with visual acuity, systematic search for complications associated with irradiation, such as cataract, raised intraocular pressure, keratitis or dry eye syndrome, and intraocular inflammation). The presence or absence of maculopathy or optic neuropathy was also investigated and was confirmed by fluorescein angiography, whenever possible. All these data were then entered into a database for computerised data analysis.

Tumour staging consisted of abdominal ultrasonography every 6 months and annual chest X-ray. The objective of the study was to evaluate the efficacy of this treatment on local and systemic tumour control, as well as the associated complications when the lesion was situated anterior to the equator.

Statistical methodology

The χ2 test was used to compare percentages and a Student test was used to compare means. A difference was considered to be significant for P<0.05.

A methodology adapted to survival data was used to study mortality and the local and distant recurrence rate. Survival rates were calculated from the first day of treatment, corresponding to insertion of the plaque until the date of the event considered (death, local relapse, metastases).

Survival curves (overall, metastasis free) were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method. The log-rank test was used to compare survival distributions according to the various prognostic parameters.

Results

During the study period, 136 patients were treated by 125I plaque brachytherapy for choroidal or ciliochoroidal melanoma anterior to the equator.

This group comprised 45 men (33.1%) and 91 women (66.9%) with a median age of 65 years, a mean age of 61 years (range: 23–91 years) and a median follow-up of 62 months (range: 13–128 months).

The tumour was situated in the right eye in 67 cases (49.3%) and in the left eye in 69 cases (50.7%). Tumour characteristics are summarised in Table 1; tumour dimensions are available for all patients.

The median dose delivered to the tumour apex was 101 Gy, with a mean of 112 Gy (range: 60–221 Gy). The dose was delivered over a mean duration of 6 days and at an average rate of 87.5 cGy/h (the dose rate and dose delivered to the apex were relatively high due to the doses delivered to the apex of small tumours, considered to be 5 mm thick).

The mean visual acuity at diagnosis was 20/50. At the end of follow-up, 121 patients (89%) were alive and 15 (11%) had died.

Death was due to metastatic melanoma for five patients (33.3%), the diagnosis of metastasis having been realised after liver and general investigations for all and in some cases liver biopsies; a second cancer for one patient (6.7%), intercurrent disease in four cases (26.7%) and an undetermined cause in five cases (33.3%). In these last cases, the only information available was the confirmation of the death by the civil registry office with no data on the status of patient at the moment of the death.

In all, 116 (95.9%) of the patients alive at the end of follow-up were disease free, but two presented systemic metastases. Three patients (2.5%) were lost to follow-up.

Metastatic disease was observed for a total of eight patients (5.9%) and involved the liver in every case. Recurrence of the ocular tumour was observed in two patients (1.5%). Secondary enucleation for complications of radiotherapy had to be performed for two patients (1.5%).

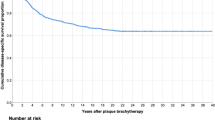

The overall survival was 93.8% (±2.1%) at 2 years and 88.3% (±3.1%) at 5 years (Figure 1). The metastasis-free interval was 98.3% (±1.1%) at 2 years and 96% (±1.3%) at 5 years.

Functional assessments showed a mean visual acuity of 20/40 at the last follow-up. The ocular complications observed were: cataract, glaucoma, keratitis, inflammation, retinal detachment, maculopathy, and optic neuropathy, presented in Table 2.

Risk factors for overall survival on univariate analysis were age greater than 65 years and initial tumour thickness greater than 4 mm (Figure 1), while involvement of the ciliary body was not identified as a significant risk factor.

No risk factor for metastases was identified, but this could be related to the very low event rate. Risk factors for cataract, glaucoma, and intraocular inflammation, the complications most frequently observed, were also investigated. Risk factors for cataract were the patient's gender and age and tumour diameter.

Statistical analysis of risk factors for glaucoma only identified gender, while the risk factors for intraocular inflammation were tumour thickness and ciliary body invasion (Figures 2 and 3).

Discussion

125I plaque brachytherapy is a standard conservative management for uveal melanoma.1 Our study confirms the good results in terms of local control of this technique for the treatment of lesions anterior to the equator, and provides a more detailed analysis of the complications of this treatment.

However, interpretation of the results of this series must take into account the selection bias of patients treated by radioactive plaque in our institute, as this treatment was only proposed for relatively small tumours. Larger lesions are often treated by proton beam radiotherapy. A female predominance was also observed while these tumours usually present a homogeneous sex distribution.1

The overall survival in our series was 89% at the end of follow-up, with a 5-year survival of 88.3%; 33.3% of deaths were directly attributable to melanoma.

In the COMS study (report 18, 2001), the overall 5-year survival rate was 82% in the brachytherapy arm, with no significant difference compared to patients treated by enucleation.1 About one-half of these deaths were attributable to melanoma, which is much higher than the 33.3% of deaths attributable to melanoma in our study. This can be partly explained by the problem of the definitive diagnosis of the cause of death, and the number of patients in whom the cause of death was not determined in our series (close to one-third). On the other hand, in the COMS protocol, special efforts were made to obtain all reports to establish the status of the patient at death.

The metastasis rate in our series was very low, but these results may have been biased by the relatively smaller dimensions of the anterior lesions treated. The most striking result compared to other studies is the relatively low local recurrence rate, which was only 1.5% in our series. Char et al6 reported a local recurrence rate of 13.3% in their series of lesions treated by radioactive iodine compared to a recurrence rate of zero for lesions treated by helium ions. In the recent COMS study, 12% of patients required enucleation because of recurrence or complications, although the enucleation rate related to each cause was not specified.1 Wilson and Hungerford7 reported a local recurrence rate of 5% in their study comparing the results of lesions treated by 125I, ruthenium or proton beam therapy, and demonstrated a comparable efficacy between proton beam and 125I, while a higher local recurrence rate (10.7%) was observed with ruthenium. In another study by Fontanesi et al,8 the authors reported a local recurrence rate of 5.6%. These results are nevertheless much better than those observed after treatment with ruthenium with a long-term recurrence rate of 36.8% in a recent study by Lommatschz et al.9 All these data are summarised in Table 3. Several possible explanations can be proposed for this low recurrence rate of anterior tumours. First of all, in our series 125I plaque brachytherapy is preferentially used in small tumours. Their anterior position allows transillumination with good visualisation of tumour margins and episcleral positioning of the plaque is not modified, in contrast with posterior lesions.10 The radioisotope used may also have played a role, as in the study by Wilson and the long-term results obtained with ruthenium.7, 9 Gunduz et al,11 who reported a global recurrence rate of 7%, did not distinguish the results according to the isotope used (a population of ciliary melanomas treated by various radioisotopes, especially cobalt, ruthenium, 125I and iridium).

In our study, the theoretical dose delivered to the tumour apex was 90 Gy with a median dose effectively received of 101 Gy, which was higher than the dose effectively received reported in other studies, as other teams use doses to the apex ranging between 70 and 75 Gy.3, 6, 8 The influence of the dose to the apex has also been identified as a risk factor in a subsequent study by Quivey et al.12

Functional results/ocular complications

The final visual acuity was excellent in the population of anterior melanomas. In the COMS study, in a series of tumours with identical characteristics, but which were essentially situated at or posterior to the equator, 31% of patients retained a visual acuity greater than 20/40 3 years after treatment, and the median visual acuity at 3 years was 20/125, that is, much lower than that observed in our study, but they treated lesions anterior and posterior to the equator and this may explain for the difference of visual outcome as well as the length of follow-up.13 The risk factors for severe loss of visual acuity identified in this study were a history of diabetes, initial tumour thickness, mushroom shape, tumour situated close to the macula and serous macular detachment, but this study did not distinguish the various complications possibly responsible for this loss of visual acuity. Post-treatment complications were frequent in our series, but they nevertheless allowed preservation of satisfactory visual acuity. Other studies have demonstrated a difference in functional results according to the site of the tumour. Finger,14 who compared two different tumour sites (anterior and posterior), did not observe any macular complications, apart from one case of cystoid macular oedema, in contrast with our study. However, the median follow-up in Finger's study was shorter than in our study and the posterior complication rate may have been higher with longer follow-up. In their study reporting all cases of melanoma of the ciliary body treated by brachytherapy, regardless of the isotope used, the posterior segment complication rate was 5% for maculopathy and 3% for optic neuropathy.11 In our series, a number of patients developed maculopathy (18.3%) or optic neuropathy (3.6%), mostly detected by fluorescein angiography, despite treatment of anterior lesions. The mechanisms leading to cystoid macular oedema are unclear, but could be related to the coexistence of other factors, such as chronic inflammation that is frequently present.

All these findings could support the hypothesis that several factors may be involved in the development of chronic macular and optic disc lesions, as well as the direct effects of irradiation of the retina and optic disc.

Cataract

Finger14 reported a cataract rate of almost 85% in their patients treated for an anterior tumour (with tumour characteristics identical to those of our series) vs 17% for posterior lesions, but he used another radioisotope, palladium. In our study, 50% of patients presented a cataract at 5 years. In the study by Fontanesi et al,8 the cataract rate was lower for lesions posterior to the equator and the time to onset after treatment was several months longer. Quivey reported a cataract rate of 14% for posterior lesions.3

Conclusion

Despite the limitations of a retrospective study, our results confirm that 125I plaque brachytherapy of uveal melanomas is a very effective technique for tumour control and is associated with a very low complication rate when the lesion is situated anterior to the equator. However, macular lesions were observed, but can probably not be attributed to irradiation alone.

References

Diener-West M, Earle JD, Fine SL, Hawkins BS, Moy CS, Reynolds SM et al. The COMS randomized trial of iodine 125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma, III: initial mortality findings. COMS Report No. 18. Arch Ophthalmol 2001; 119(7): 969–982.

Bosworth JL, Packer S, Rotman M, Ho T, Finger PT . Choroidal melanoma: I-125 plaque therapy. Radiology 1988; 169(1): 249–251.

Quivey JM, Char DH, Phillips TL, Weaver KA, Castro JR, Kroll SM . High intensity 125-iodine (125I) plaque treatment of uveal melanoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1993; 26(4): 613–618.

Gunduz K, Shields CL, Shields JA, Cater J, Freire JE, Brady LW . Radiation retinopathy following plaque radiotherapy for posterior uveal melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol 1999; 117(5): 609–614.

Packer S . Iodine-125 radiation of posterior uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology 1987; 94(12): 1621–1626.

Char DH, Quivey JM, Castro JR, Kroll S, Phillips T . Helium ions versus iodine 125 brachytherapy in the management of uveal melanoma. A prospective, randomized, dynamically balanced trial. Ophthalmology 1993; 100(10): 1547–1554.

Wilson MW, Hungerford JL . Comparison of episcleral plaque and proton beam radiation therapy for the treatment of choroidal melanoma. Ophthalmology 1999; 106(8): 1579–1587.

Fontanesi J, Meyer D, Xu S, Tai D . Treatment of choroidal melanoma with I-125 plaque. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1993; 26(4): 619–623.

Lommatzsch PK, Werschnik C, Schuster E . Long-term follow-up of Ru-106/Rh-106 brachytherapy for posterior uveal melanoma. Results after beta-irradiation (106Ru/106Rh) of choroidal melanomas: 20 years' experience. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2000; 238(2): 129–137.

Williams DF, Mieler WF, Jaffe GJ, Robertson DM, Hendrix L . Magnetic resonance imaging of juxtapapillary plaques in cadaver eyes. Br J Ophthalmol 1990; 74(1): 43–46.

Gunduz K, Shields CL, Shields JA, Cater J, Freire JE, Brady LW . Plaque radiotherapy of uveal melanoma with predominant ciliary body involvement. Arch Ophthalmol 1999; 117(2): 170–177.

Quivey JM, Augsburger J, Snelling L, Brady LW . 125I plaque therapy for uveal melanoma. Analysis of the impact of time and dose factors on local control. Cancer 1996; 77(11): 2356–2362.

Melia BM, Abramson DH, Albert DM, Boldt HC, Earle JD, Hanson WF et al. Collaborative ocular melanoma study (COMS) randomized trial of I-125 brachytherapy for medium choroidal melanoma. I. Visual acuity after 3 years COMS report no. 16. Ophthalmology 2001; 108(2): 348–366.

Finger PT . Tumour location affects the incidence of cataract and retinopathy after ophthalmic plaque radiation therapy. Br J Ophthalmol 2000; 84(9): 1068–1070.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

None of the authors have any financial interests in the drugs or devices described in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lumbroso-Le Rouic, L., Charif Chefchaouni, M., Levy, C. et al. 125I plaque brachytherapy for anterior uveal melanomas. Eye 18, 911–916 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6701361

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6701361

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Neue therapeutische Möglichkeiten bei iridoziliären Tumoren

Der Ophthalmologe (2019)

-

Ocular complications following I-125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma

Eye (2009)