Abstract

Purpose

To describe the relations between foveal avascular zone (FAZ) size and outline in patients presenting diabetic retinopathy.

Methods

110 high-quality fluorescein angiograms from 110 diabetics were chosen from our digital retinal image databank. Patients with significant media opacities, macular scars, macular hard exsudates, high ametropia, and associated macular pathology were excluded. Both FAZ perimeter and surface area were measured with image analysis software. FAZ outline was graded according to ETDRS report Number 11 (from 0=normal to 4=capillary outline completely destroyed). Data were compared to that of 31 healthy controls. FAZ surface in diabetics was compared to that of controls and FAZ surface was compared to FAZ grade, FAZ perimeter and retinopathy stage in diabetics. Quantitative variables were compared using the U-test of Mann–Whitney or Kruskal–Wallis test and correlations between quantitative variables were estimated with the Spearmann coefficient.

Results

All patients presented diabetic retinopathy (54 BDR, 30 PPDR, 26 PDR). FAZ size was larger in diabetics than controls (P<0.001). In diabetics, FAZ size increased with FAZ grade (P<or=0.006 except between grades 1 and 2=NS) and with retinopathy stage (P<or=0.024). As retinopathy advanced, there was a higher proportion of altered FAZ outlines (P=0.003).

Conclusions

This study confirms capillary alteration to be the cause of increase in FAZ size in diabetics and presents an alternative evaluation method of the FAZ to FAZ size measurement. No qualitative studies using the ETDRS FAZ grading scale have been performed to our knowledge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In fluorescein angiographic analysis of the retina, the centre of the macula is generally capillary-free, this area being named the foveal avascular zone (FAZ). There is a large interindividual variability of FAZ size in the normal subject.1 It is known that the FAZ enlarges in diabetic retinopathy, and appears to get larger as the stage of retinopathy advances.2, 3 Capillary dropout may also occur just outside of the FAZ, at the level of the perifoveolar capillary network, this being measured by the perifoveal intercapillary area on the SLO angiographic camera system.2, 4 The purpose of this work was to examine the FAZ in a diabetic population with the diagnosis of retinopathy in order to: firstly, confirm advancing FAZ abnormalities with the stage of diabetic retinopathy, and secondly, correlate quantitative FAZ measurements (surface, perimeter) with a qualitative assessment (outline) of the FAZ.

Patients and methods

The ophthalmological records of patients with the diagnosis of diabetic retinopathy (DR) who had undergone fluorescein angiography were reviewed. DR was classified clinically using ETDRS criteria5 simplified into ‘background and less than severe nonproliferative DR’ (BDR, < level 53), ‘preproliferative or severe non proliferative DR’ (PPDR, level 53 to <level 61), or ‘proliferative DR’ (PDR, level 61 or greater). Refraction, slit lamp examination, and macular status (focal or diffuse oedema) were noted. Age, duration, and type of diabetes were also noted. Patients with significant media opacities, macular scars, laser photocoagulation inside the temporal arcades, hard exsudates in the foveal region, high ametropia (greater than ±6 diopters) and associated macular pathology (epiretinal membrane, macular hole, choroidal new vessels) were excluded.

Fluorescein angiography had been performed in standard fashion following rapid injection of 5 ml of 10% sodium fluorescein into the antecubital vein. The TopCon 50IA camera (50° lens) and ImageNet® digital system were used. For each patient, a frame was chosen that presented high definition, with the fovea well centred. Digital images of the FAZ were exported to the PC-based image analysis software package Image J® (Image J® 1.29 × , Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, USA). The FAZ was manually outlined and measurements of both perimeter and surface were made in pixels. For very small FAZs, the outline of the largest central capillary-free zone was used. The actual size of the FAZ was calculated by adjusting for magnification of the fundus camera (10.88 μm per pixel, data provided by TopCon laboratories) and the ocular refraction using the formula of Bengtsson and Krakau.6

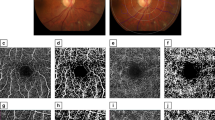

FAZ outline was classified according to the ETDRS grading system,7 from 0 (normal), to 1 (questionable), 2 (less than half the original circumference destroyed), 3 (more than half the contour destroyed but some remnants remain), and 4 (capillary outline completely destroyed). We did not retain angiograms with a grade 8 FAZ outline (cannot grade, therefore cannot measure). Figure 1a–f give examples of FAZ outlines.

Statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS 10 software package. Nonparametric tests were preferred as the population of subgroups was rarely above 30 (ANOVA requiring a normal distribution in subgroups). Quantitative variables were compared using the U-test of Mann–Whitney or Kruskal–Wallis test according to the number of groups to compare. Correlations between quantitative variables were estimated with the Spearmann coefficient. P-values less than 0.05 (two-side tests) were considered as statistically significant, except for the 2 × 2 comparisons for the ‘FAZ grade’ variable where P-values less than 0.0106 (two-side tests) were considered as statistically significant to protect against multiple comparisons.

A control group of 31 patients was constituted from a random sample of eyes without retinovascular or macular pathologic conditions who had undergone fluorescein angiography on the same digital camera system.

Results

All patients presented DR (54 BDR, 30 PPDR, 26 PDR; 44 Type 1 and 66 Type 2). None of the patients presented clinically significant macular oedema. Clinical and ocular characteristics appear in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences in age or sex ratio between the patients and controls. There was no correlation between age and FAZ size in the controls (r=−0.327, P>0.10). Table 2a shows the quantitative FAZ measurements (surface area) compared to DR stage (BDR, PPDR, PDR), along with controls. Significance levels are given in Table 2b. The controls contained a large proportion of small FAZ compared to the diabetic patients (10/31 vs 8/110 presented a FAZ less than or equal to 0.10 mm2). Quantitative FAZ measurements correlated well with each other in the diabetics (Figure 2, perimeter vs surface), but with a weaker correlation coefficient (cc=0.908) and higher covariance (cov=0.41) in the diabetics than in the controls (Figure 3 perimeter vs surface, cc=0.959, cov=0.036).

Qualitative abnormalities of the FAZ (depicted in Figure 1b–f) correlated well with retinopathy stage (Table 3) and generally well with quantitative (FAZ surface area) abnormalities (Table 4a and b) also. Table 4a and b show that FAZ surface measured in mm2 increased significantly with FAZ outline grade, in all grades compared 2 × 2, except for grade 1 (0.28 mm2 ±0.15) vs grade 2 (0.29 mm2 ±0.09), P=0.67.

Discussion

The foveal avascular zone has been measured by trypsin digest,8 by psychophysical methods1, 9, 10 and by fluorescein angiography. 1, 2, 3, 4, 11, 12 The SLO system, used by Arend2 and by Sander4 permits a good definition of the FAZ and of the perifoveal intercapillary area (PIA) in a higher percentage of cases than the conventional fundus camera, as it uses superimposed images of different depths, allowing to sum the fluorescence and create greater contrast.13 With classic intravenous angiography, used by Bresnick,11, Mansour3 and in our study, proper FAZ analysis may be readily performed in a sufficient number of cases. Anecdotaly, FAZ analysis may even be possible with oral fluorescein angiography in up to 47% of cases using the SLO compared to 2% of cases with classic angiography.13

It is not surprising to find the FAZ dimensions larger in the diabetic patients compared to the controls and within the diabetic patients, as retinopathy stage advances. This confirms previous the studies.2, 3, 4 FAZ enlargement occurs also with the duration of diabetes, but not independently of retinopathy stage in our study. We found no increase of FAZ surface with the age of controls, like Mansour3 and Bresnick,11 yet unlike Laatikainen14 and Wu.12 Correlation of quantitative measurements between themselves (ie perimeter vs surface) show a strong correlation with a cc of 0.91 in the diabetics but weaker than in controls (cc of 0.96). This is explained by the higher amount of irregular outlines in the diabetics, thus increasing the perimeter for a given same surface value compared to a healthy control (confirming the ‘greater effect on the circumference than on the area’ noted by Bresnick).11

ETDRS qualitative grading of the foveal avascular zone has not yet been used to our knowledge in clinical studies. It has been well described in ETDRS Report Number 11.7 It correlates well with the quantitative measurements of surface and perimeter. Findings validated for quantitative measures (increase with stage of diabetic retinopathy) are also found with the qualitative measures. It has been well documented that the FAZ may be considered ‘normal’ in a nondiabetic population with measures ranging from ‘0’ mm in diameter (FAZ not observable, or central macula crossed by vessels1, 15), to over 1.0 mm in diameter9 or 2 mm2 in surface area.3 The overlap of size between non-diabetics and diabetics may therefore be large, not letting one say whether a given FAZ is ‘normal’ or ‘pathologic’ in a diabetic patient, when judging by size alone. Given the absence of a completely standardized method of measuring fundus landmarks (Arend's2 normals have a FAZ size of 0.231 mm2, Mansour's3 0.405 mm2, Bresnick's11 0.35 mm2, Sander's15 0.367 mm2, and ours 0.152 mm2, undoubtedly due to the high percentage of very small FAZs in our controls) we believe that this method of assessment may be useful in future studies of the FAZ, either complementary to, or in place of a quantitative assessment of the FAZ. Perifoveal intercapillary area has also been shown to be increased in diabetics without retinopathy or in early stage DR compared to healthy controls, and to increase with the stage of DR.2, 4 However, as with FAZ measurement, PIA measurement has not yet been standardized, Arend summing 60 areas within the central 5° and Sander summing the two innermost circles of capillary loops. PIA evaluation also requires the SLO system. Qualitative grading of the FAZ provides another evaluation of the macular microcirculation, requiring no special software, and available to teams that do not have access to FAZ and PIA measurements with the SLO camera.

References

Bird AC, Weale RA . On the retinal vasculature of the human fovea. Exp Eye Res 1974; 19: 409–417.

Arend O, Wolf S, Jung F, Bertram B, Postgens H, Toonen H et al. Retinal microcirculation in patients with diabetes mellitus : Dynamic and morphological analysis of perfoveal capillary network. Br J Ophthalmol 1991; 75: 514–518.

Mansour AM . Measuring fundus landmarks. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1990; 31: 41–42.

Sander B, Larsen M, Engler C et al. Early changes in diabetic retinopathy : capillary loss and blood-retina barrier permeability in relation to metabolic control. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1994; 72: 553–559.

ETDRS research group. Fundus photographic risk factors for progression of diabetic retinopathy. ETDRS report number 12. Ophthalmology 1991; 98 (5 Suppl): 823–833.

Bengtson B, Krakau CE . Some essential optical features of the Zeiss fundus camera. Acta Ophthalmol. 1977; 55: 123–131.

ETDRS research group. Classification of diabetic retinopathy from fluorescein angiograms. ETDRS report number 11. Ophthalmology 1991; 98 (Suppl): 807–822.

Bligard E, De Venecia G, Wallow I, Bresnick G, Syrjala S . Aging changes of the parafoveolar vasculature : a trypsin digest study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1982; 22 (Suppl): 8.

Bradley A, Applegate RA, Zeffren BS, van Heuven WAJ . Psychophysical measurement of the size and shape of the human foveal avascular zone. Ophthal Physiol Opt 1992; 12: 18–23.

Yap M, Gilchrist J, Weatherill J . Psychophysical measurement of the foveal avascular zone. Ophthal Physiol Opt 1987; 7: 405–410.

Bresnick GH, Condit R, Syrjala S, Palta M, Groo A, Korth K . Abnormalities of the foveal avascular zone in diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 1984; 102: 1286–1293.

Wu L, Huang Z, Wu D, Chan E . Characteristics of the capillary-free zone in the normal human macula. Jpn J Ophthalmol 1985; 29: 406–411.

Garcia CR, Rivero ME, Bartsch DU, Takamiya A, Hirokawa H, Clark T et al. Oral fluorescein angiography with the confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Ophthalmology 1999; 106 (6): 1114–1118.

Laatikainen L, Larinkari J . Capillary free area of the fovea with advancing age. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1977; 16: 1154–1157.

Sander B, Larsen M, Engler C, Lund-Andersen H . Absence of foveal avascular zone demonstrated by laser scanning fluorescein angiography. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1994; 72: 550–552.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Conrath, J., Giorgi, R., Raccah, D. et al. Foveal avascular zone in diabetic retinopathy: quantitative vs qualitative assessment. Eye 19, 322–326 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6701456

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6701456

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Morphological characteristics of the foveal avascular zone in pathological myopia and its relationship with macular structure and microcirculation

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2024)

-

Foveal avascular zone size and mfERG metrics in diabetes and prediabetes: a pilot study of the relationship between structure and function

Documenta Ophthalmologica (2023)

-

Assessment of early macular microangiopathy in subjects with prediabetes using optical coherence tomography angiography and fundus photography

Acta Diabetologica (2023)

-

Age-related assessment of foveal avascular zone and surrounding capillary networks with swept source optical coherence tomography angiography in healthy eyes

Eye (2022)

-

Diabetic macular ischemia

Acta Diabetologica (2022)