Abstract

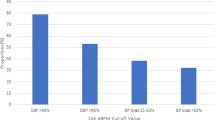

End-digit preference describes the disproportionate selection of specific end digits. The rounding of figures might lead to either an under- or over-recording of blood pressure (BP) and a lack of accuracy and reliability in treatment decisions. A total of 85 000 BP values taken from computerised general practice records of ischaemic heart disease patients in England between 2001 and 2003 were examined. Zero preference accounts for 64% of systolic and 59% of diastolic readings, compared with an expected frequency of 10% (P<0.000001). Even numbers are more frequently seen than odd numbers. In all, 64% of nonzero systolic recordings and 65% of diastolic recordings ended in even numbers, compared with expected proportions of 44% (P<0.0001). Among the nonzero even numbers, eight is the most frequently observed: 28% of systolic and 31% of diastolic recordings compared with an expected proportion of 25% (P<0.0001). Among the five nonzero odd numbers, five is the most frequently observed end digit, representing 59% systolic and 62% of diastolic compared with an expected level of 20% (P<0.00001). English general practice displays marked end-digit preference. This is strongly for the end-digit zero. However, there is more use of other enddigits, notably 8 and 5. This bias potentially carries important treatment consequences for this high-risk population.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

de Lusignan S, Hague NJ . The PCDQ (Primary Care Data Quality) Programme. Bandolier/Impact. January 2001. URL:http://www.jr2.ox.ac.uk/Bandolier/booth/mgmt/PCDQ.html.

de Lusignan S, Harvey M, Hague N, Yates C . A case study from a Sussex Primary Care Group: improving secondary prevention in coronary heart disease using an educational intervention. Br J Cardiol 2002; 9: 362–368.

de Lusignan S, Dzregah B, Hague N, Chan T . Cholesterol management in patients with ischaemic heart disease: an audit-based appraisal of progress towards clinical targets in primary care. B J Cardiol 2003; 10: 223–228.

Wingfield D . Observational precision in general practice data: a technique for analysis and audit. IMA J Math Appl Med Biol 1995; 12: 275–281.

Chatellier G et al. Home self blood pressure measurement in general practice. The SMART study. Self-measurement for the Assessment of the Response to Trandolapril. Am J Hypertens 1996; 9: 644–652.

Torrance C, Serginson E . An observational study of student nurses' measurement of arterial blood pressure by sphygmomanometry and auscultation. Nurse Educ Today 1996; 16: 282–286.

Wen SW et al. Terminal digit preference, random error, and bias in routine clinical measurement of blood pressure. J Clin Epidemiol 1993; 46: 1187–1193.

Staessen JA, O'Brien ET, Thijs L, Fagard RH . Modern approaches to blood pressure measurement. Occup Environ Med 2000; 57: 510–520.

Wingfield D et al. Syst-Eur Investigators. Terminal digit preference and single-number preference in the Syst-Eur trial: influence of quality control. Blood Press Monit 2002; 7: 169–177.

Fleiss L . Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions, 2nd edn, Wiley: Newyork, 1981.

Ramsay LE et al. Guidelines for management of hypertension: report of the third working party of the British Hypertension Society. J Hum Hypertens 1999; 13: 569–592.

Hansson L et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering and low dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. Lancet 1998; 351: 1755–1762.

Dahlof B et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the losartan intervention for endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet 2002; 359: 995–1003.

Yarows SA, Brook RD . Measurement variation among 12 electronic home blood pressure monitors. Am J Hypertens 2000; 13: 276–282.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the general practices and primary care organisations who are members of the PCDQ programme and meet half its costs, South Thames IM+T who sponsored the development of the programme, and MSD who have sponsored the core team for the last 2 years through an unconditional educational grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lusignan, S., Belsey, J., Hague, N. et al. End-digit preference in blood pressure recordings of patients with ischaemic heart disease in primary care. J Hum Hypertens 18, 261–265 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jhh.1001663

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jhh.1001663

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Relations of body weight status in early adulthood and weight changes until middle age with hypertension in the Chinese population

Hypertension Research (2016)

-

Challenges in standardization of blood pressure measurement at the population level

BMC Medical Research Methodology (2015)

-

The QICKD study protocol: a cluster randomised trial to compare quality improvement interventions to lower systolic BP in chronic kidney disease (CKD) in primary care

Implementation Science (2009)

-

Blood pressure recording bias during a period when the Quality and Outcomes Framework was introduced

Journal of Human Hypertension (2009)

-

End-digits preference for self-reported height depends on language

BMC Public Health (2008)