Abstract

Caren Grown explores the linkages between trade liberalization and the provision of and access to sexual and reproductive health services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As Lipson (2006) states, ‘In most countries, trade in health-related goods and services is a relatively minor factor affecting the availability, cost and quality of health services. The ways in which each country organizes, finances, and regulates health services are usually much more important determinants of whether countries are able to ensure the delivery of basic health care to their people, without financially burdening the poor. But trade can influence some particularly critical health goods, such as life-saving pharmaceuticals, or the availability of certain services if they are only offered by foreign-owned companies. It is these situations where trade and rules governing such trade come into play’.

Most indicators cover the medical and demographic aspects of reproductive health. Indicators are being developed to capture the socio-political dimensions of reproductive health but they are not available for a large number of countries. There are few indicators for reproductive rights that are agreed upon and available across countries.

Although there are distinct country trends and modes of transmission, many analysts highlight gender inequality – especially the rules governing sexual relationships and sexual violence – as a major factor driving the increase of the epidemic (Rao Gupta, 2000; UNAIDS, 2004).

For example, concentration of certain medical procedures in urban areas when most of the population is rural or the imposition of user fees that most cannot pay illustrate the misfit between problems (needs) and services.

Other agreements, such as the Agreement on Agriculture, may also affect reproductive health outcomes via changes in food consumption and nutritional status.

As of 2003, 54 countries, nearly half of the World Trade Organization members, have made commitments to at least one of the trading modes under GATS.

Prior to the TRIPS Agreement, a substantial number of developing countries did not adequately cover intellectual property rights for medicines and pharmaceutical products. In addition, patent coverage was highly inconsistent between some developing countries, ranging from as little as three years (Thailand) to as long as 16 years (South Africa). These conditions generally favoured the local production of less-expensive generic medicines where possible. See Williams (2001).

Some reproductive health products – like certain forms of contraception – are off patent so TRIPS will not apply. It should also be noted that even if technology is available and affordable to women, other barriers in the health care system may prevent women from having full access to prevention and treatment of reproductive health problems. For instance, a study conducted on clinical practices related to sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in gynecological and antenatal programs in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where drugs are wildly available, revealed that doctors found it difficult to disclose to married women they had an STD, and to discuss how they contracted the infection. See Giffen and Lowndes (1999).

Another indirect pathway is through the household. For instance, changes in husband's status or in the status of other earners in the household may affect women's reproductive health and her access to services (if it is through another earner's health insurance).

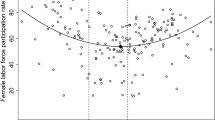

In Taiwan, Hong Kong, South Korea, and Singapore, as well as in Mexico's maquiladoras, women's share of manufacturing employment first increased and then fell in later stages of industrialization.

In some countries, such as in Latin America, economic restructuring and globalization have led to the feminization of agriculture as women seek remunerative employment to supplement declining family income (Deere, 2004). Countries that export unprocessed primary products (e.g., ores) do not fit the stylised fact for agriculturally based economies.

The sex trade is also one of the fastest growing and most profitable service industries; see UN (1999).

It is important to recognize that apart from women's own employment, changes in husband's employment status or that of other earners in the household may affect women's reproductive health and access to services, for example, if husbands’ lose health insurance that covers all family members. However, these will not be considered further here.

It is important to note that these studies do not control for selection bias; it may be that other characteristics of workers in the horticultural industry are responsible for this outcome.

References

Amin, Sajeda. (2005) ‘Implications of trade liberalization for working women's marriage: Case studies of Bangladesh, Egypt and Vietnam’, in Caren Grown, Anju Malhotra and Elissa Braunstein (eds.) Guaranteeing Reproductive Health and Rights: The role of trade liberalization, London: Zed Books.

Amin, Sajeda, Ian Diamond, Ruchira T. Naved and Margaret Newby (1998) ‘Transition to Adulthood of Female Garment-Factory Workers in Bangladesh’, Studies in Family Planning 29 (2): 185–200.

Balakrishnan, Radhika (ed.) (2002) The Hidden Assembly Line: Gender dynamics of subcontracted work in a global economy, Bloomfield, CT: Kumarian Press.

Barrientos, Stephanie (2001) ‘Gender, Flexibility, and Global Value Chains’, IDS Bulletin 32 (3): 83–93, Brighton UK: Institute of Development Studies.

Chanda, Rupa (2001) ‘Trade in Health Services’, Commission on Macroeconomics and Health Working Paper Series, Paper No WG4: 5. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Chen, Martha, Jennefer Sebstad and Lesley O’Connell (1999) ‘Counting the Invisible Workforce: The case of homebased workers’, World Development 27 (3): 603–610.

Das, Maitreyi and Caren Grown (2002) ‘Trade Liberalization, Women's Employment, and Reproductive Health: What are the linkages and entry points for policy and action?’ International Center for Research on Women Working Paper, Washington DC: International Center for Research on Women.

Deere, Carmen Diana (2004) ‘The Feminization of Agriculture? Economic Restructuring in Rural Latin America’, Background paper for UNRISD Policy Report on Gender and Development: An UNRISD contribution to Beijing Plus Ten. Geneva: UNRISD.

Denman, Catalina A., Leonor Cedillo and Siobán D. Harlow (2003) ‘Work and Health in Export Industries at National Borders’, in Jody Heymann (ed.) Global Inequalities at Work: Work's impact on the health of individuals, families, and societies, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dixon-Mueller, Ruth and Adrienne Germain (2000) ‘Reproductive Health and the Demographic Imagination’, in Harriet B. Presser and Gita Sen (eds.) Women's Empowerment and Demographic Processes, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dolan, Catherine, John Humphrey and Carla Harris-Pascal (1999) ‘Horticulture Commodity Chains: The impact of the U.K. market on the African fresh vegetable industry’, IDS Working Paper No. 96. Brighton, U.K: Institute of Development Studies.

Eskenazi, Brenda, Sylvia Guendelman and Eric P. Elkin (1993) ‘A Preliminary Study of Reproductive Outcomes of Female Maquiladora Workers in Tijuana Mexico’, American Journal of Industrial Medicine 24: 667–676.

Freeman, Carla (2000) High Tech and High Heels in the Global Economy: Women, work, and pink collar identities in the Caribbean, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Friedemann-Sanchez, G. (2004) ‘Assets, Wage Income, and Social Capital in Intrahousehold Bargaining Among Women Workers in Colombia's Cut-flower industry’, Paper presented at Workshop on Women and the Distribution of Wealth at Yale Center for International and Area Studies, New Haven, CT. November.

Giffen, Karen and Catherine M. Lowndes (1999) ‘Gender, Sexuality, and the Prevention of Sexually Transmissible Diseases: A Brazilian study of clinical practice’, Social Science and Medicine 48: 283–292.

Haddad, Lawrence, John Hoddinott and Harold Alderman (1997) ‘Intrahousehold Resource Allocation, an Overview’, in Lawrence Haddad, John Hoddinott and Harold Alderman (eds.) Intrahousehold Resource Allocation in Developing Countries: Models methods and policy, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

Hettiarachchy, Tilak and Stephen L. Schensul (2001) ‘The Risks of Pregnancy and the Consequences among Young Unmarried Women Working in a Free Trade Zone in Sri Lanka’, Asia Pacific Population Journal 16 (2): 125–140.

Hugo, Graeme J. (2000) ‘Migration and Women's Empowerment’, in Harriet B. Presser and Gita Sen (eds.) Women's Empowerment and Demographic Processes: Moving beyond Cairo, Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Kabeer, Naila (2000) The Power to Choose: Bangladeshi women and labour market decisions in London and Dhaka, London: Verso.

Kickbusch, Ilona, Kari A. Hartwig and Justin M. List (eds.) (2005) Globalization, Women, and Health in the Twenty-First Century, New York: Palgrave-Macmillan.

Lipson, Debra J. (2006) ‘Implications of The General Agreement on Trade in Services for Reproductive Health Services’, in Caren Grown, Anju Malhotra, and Elissa Braunstein (eds.) Guaranteeing Reproductive Health and Rights: The role of trade liberalization, London, UK: Zed Books.

Luke, Nancy (2001) ‘Cross-Generational and Transactional Sexual Relations in Sub-Saharan Africa: A review of the evidence on prevalence and implications for negotiation of safe sexual practices for adolescent girls’. Paper prepared for the International Center for Research on Women as part of the AIDSMark Project. Washington, D.C.: International Center for Research on Women.

Malhotra, Anju and Sanyukta Mathur (2000) ‘The Economics of Young Women's Sexuality in Nepal’. Paper Presented at the IAFFE Conference Istanbul, Turkey.

Newman, Constance (2001) Gender, Time Use and Change: Impacts of agricultural employment in ecuador, Washington, DC: World Bank.

O'Connell Davidson, Julia and Jacqueline Sanchez-Taylor (1999) ‘Fantasy Island: Exploring the Demand for Sex Tourism’, in Kamala Kempadoo Sun, sex and gold: tourism and sex work in the Caribbean, Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Ozler, Sule (2001) ‘Export Led Industrialization and Gender Differences in Job Creation and Destruction, Micro Evidence from Manufacturing Mector’, UCLA Working Paper.

Rao Gupta, Geeta (2000) ‘Gender, Sexuality, and HIV/AIDS: The what, the why, and the how, Plenary address at the 13th International AIDS Conference, Durban, South Africa.

Rodríguez, Daniel and Sylvia Venegas (1991) Los Trabajadores de la fruta en cifras, Santiago: GEA.

Sassen, Saskia (1998) ‘Informalization in Advanced Market Economies’. Issues in Development-Discussion Paper 20. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

Subramaniam, Vanitha (2001) ‘The Impact of Globalization on Women's Reproductive Health and Rights: A regional perspective’, Development 42 (4): 145–149.

Thrupp, Lori Ann, Gilles Bergeron and William Waters (1995) ‘Bittersweet Harvests for Global Supermarkets: Challenges in Latin America's agricultural export boom’. Washington DC: World Resources Institute.

UN (1999) 1999 World Survey on the Role of Women in Development: Globalization, gender, and work, New York: United Nations.

UN (2002) Demographic Yearbook, New York: United Nations.

UNAIDS (1998) ‘A Global Overview of the AIDS Epidemic’, in 1998 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic.

UNAIDS (2004) ‘A Global Overview of the AIDS Epidemic’, in 2004 Report on the global AIDS Epidemic.

UNAIDS/WHO (2004) The AIDS Epidemic Update, Geneva: UNAIDS.

UNCTAD (2004) Trade and Development Report 2004, Geneva: United Nations.

UNCTAD/WHO (1998) International Trade in Health Services, A Development Perspective, Geneva: United Nations.

Upadhyay, Ushma D. (2000) ‘India's New Economic Policy of 1991 and its Impact on Women's Poverty and AIDS’, Feminist Economics 6 (3): 105–122.

Venegas, Sylvia (1993) ‘Programas de apoyo a temporeros y temporeras en Chile’, in Sergio Gomes and Emilio Klein (eds.) Los pobres del campo, El Trabajador Eventual, Santiago: FLACSO/PREALC/OIT.

Williams, Mariama (2001) ‘The TRIPS and Public Health Debate: An overview’, International Gender and Trade Network Research Paper, Geneva: International Gender and Trade Network.

WTO (2003) Understanding WTO.

WTO (2004) International Trade Statistics 2004.

World Bank (2004) World Development Indicators. Washington DC: World Bank.

Additional information

Explores the linkages between trade liberalization and sexual and reproductive health

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grown, C. Trade Liberalization and Reproductive Health: A framework for understanding the linkages. Development 48, 28–42 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.development.1100198

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.development.1100198