Abstract

Background

To meet the challenge of an aging population, providers andpayors must optimize chronic wound care outcomes and contain costs.

Objective

To explore the costs, outcomes, and effects of outcomes on costs of pressure and venous ulcer woundcare protocols.

Design

Modeling study using outcomes from a literature review.

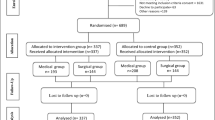

Methods

The cost of 12 weeks of wound care was modeled for a hypothetical managed-care plan. This included 100 000 covered lives and used a peer-validated wound care protocol. Only modalities with a pooled evidence base of at least 100 wounds were used to populate the model. Costs excluded supportive treatments.

Results

26 studies of three pressure ulcer protocols (n = 519) and three venous ulcer protocols (n = 883) qualified for inclusion in the models. After 12 weeks, the weighted average proportion of ulcers healed, and cost per ulcer healed, ranged from 48 to 61% and from $US910 to $US2179 (2000 values) for pressure ulcers, and from 39 to 51% and $US1873 to $US15 053 for venous ulcers. For a hypothetical managed-care plan, the difference between the least and most cost-effective modalities was $US1.9 million for pressure ulcers and $US5.8 million for venous ulcers. Observed differences were generally attributable to variances in outcomes and cost differences related to frequency of dressing changes. Pressure ulcer care takes place in inpatient care settings; venous ulcers are managed on an outpatient basis. Physician visit frequencies are once every four weeks for pressure ulcers and once each week for venous ulcers. Wound sizes ranged from 2.5cm2 to 5.6cm2 for pressure ulcers and 5.4cm2 to 10cm2 for venous ulcers. All patients with pressure ulcers required pressure relief, nutritional support and incontinence management; venous ulcers required gradient compression. Costs per patient healed were lowest for pressure ulcers with hydrocolloids and highest with saline gauze (this is a manpower issue). Costs to heal venous ulcers were highest with human skin construct and lowest for 12-week management with hydrocolloid.

Conclusions

Despite the limitations of the models (as a result of incomplete study data), this analysis confirms that defining wound care costs solely as cost of products used is inaccurate and can be expensive.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Use of tradenames is for product identification only and does not imply endorsement.

References

Murray CJL, Lopez A, editors. The global burden of disease 1990. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1996

Neil JA, Munjas BA. Living with a chronic wound: the voices of sufferers. Ostomy Wound Manage 2000; 46(5): 28–38

Phillips T, Stanton B, Provan A, et al. A study of the impact of leg ulcers on quality of life: financial, social, and psychologic implications. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994; 31: 49–53

van Rijswijk L, Gottlieb D. Like a terrorist. Ostomy Wound Manage 2000; 46(5): 25–6

Andersson E, Hansson C, Swanbeck G. Leg and foot ulcerprevalence and investigation of the peripheral arterial and venous circulation in a randomized elderly population: an epidemiological survey and clinical investigation. Acta Derm Venereol (Stockh) 1993; 73: 57–61

Phillips T. Chronic cutaneous ulcers: etiology and epidemiology. J Invest Dermatol 1994; 102 Suppl 10A: S38–41

Angle N, Bergan JJ. Clinical review: chronic venous ulcer. BMJ 1997; 314: 1019–23

Bergstrom N, Bennett MA, Carlson CE, et al. Treatment of pressure ulcers. Clinical practice guideline, no.15. Rockville (MD): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. AHCPR Publication No. 95-0652, 1994 Dec

Langemo DK, Olson B, Hunter S, et al. Incidence and prediction of pressure sores in five patient care settings. Decubitus 1991; 4(3): 25–30

Allman RM, Goode PS, Patrick MM, et al. Pressure ulcer risk factors among hospitalized patients with activity limitation. JAMA 1995; 273: 865–70

Brandeis GH, Oois WL, Hossain M, et al. A longitudinal study of risk factors associated with the formation of pressure ulcers in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994; 42: 388–93

Wood CR, Margolis DJ. The cost of treating venous ulcers to complete healing using an occlusive dressing and a compression bandage. Wounds 1992; 4: 138–41

Kerstein MD, Gahtan V. Outcomes of venous ulcer care: results of a longitudinal study. Ostomy Wound Manage 2000; 46(6): 22–9

Xakellis GC, Frantz R. The cost of healing pressure ulcers across multiple health care settings. Adv Wound Care 1996; 9(6): 18–22

Bolton LL, van Rijswijk L, Shaffer FA. Quality wound care equals cost-effective wound care: a clinical model. Nurs Manage 1996; 27(7): 30–7

Ballard-Krishnan S, van Rijswijk L, Polansky M. Pressure ulcers in extended care facilities: report of a survey. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 1994; 21(1): 4–11

Kimura S, Pacala JT. Pressure ulcers in adults: family physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, practice preferences, and awareness of AHCPR guidelines. J Fam Pract 1997; 44: 361–8

University of Pennsylvania. Venous leg ulcer guideline [online]. Available from: URL: http://www.guideline.gov/FRAMESETS-/guideline_fs.asp?.view=fullsummary&guidelines [Accessed 2000 Jun 6]

Hutchinson JJ, McGuckin M. Occlusive dressings: a microbiologic and clinical review. Am J Infect Control 1990; 18(4): 257–68

Drug Topics® Red Book®. Montvale (NJ): Medical Economics Company, Inc., 2000

United States Department of Health and Human Services. National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses. Rockville (MD): DHHS, Bureau of Health Professions, Division of Nursing, 1996 Mar

United States Department of Health and Human Services; Health Care Financing Administration. Fed Regist 1999 Nov 2; (64): 211: 59380–590

Einarson TR. Pharmacoeconomic applications of meta-analysis for single groups using antifungal onychomycosis lacquers as an example. Clin Ther 1997; 19(3): 559–69

Gold M, Siegel J, Russel L, et al. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1996

Bale S, Hagelstein S, Banks V, et al. Costs of dressings in the community. J Wound Care 1998; 7(7): 327–30

Thomas S, Banks V, Bale S, et al. A comparison of two dressings in the management of chronic wounds. J Wound Care 1997; 6(8): 383–6

Matzen S, Peschardt A, Alsbjrrn B. A new amorphous hydro-colloid for the treatment of pressure sores: a randomized controlled study. Scand J Plast Reconstr Hand Surg 1999; 33: 13–5

Thomas DR, Goode PS, LaMaster K, et al. Acemannan hydrogel dressing versus saline dressing for pressure ulcers: a randomized, controlled trial. Adv Wound Care 1998; 11: 273–8

Kraft MR, Lawson L, Pohlmann B, et al. A comparison of epilock and saline dressings in the treatment of pressure ulcers. Decubitus 1993; 6(6): 42–8

Xakellis GC, Chrischilles EA. Hydrocolloid versus saline-gauze dressings in treating pressure ulcers: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1992; 73: 463–9

Alm A, Hornmark A, Fall P, et al. Care of pressure sores: a controlled study of the use of a hydrocolloid dressing compared with wet saline gauze compresses. Acta Derm Venerol 1989; 149 Suppl: 1–10

Fowler E, Goupil DL. Comparison of the wet-to-dry dressing and a copolymer starch in the management of debrided pressure sores. J Enterostomal Ther 1984; 11(1): 22–5

Hondé C, Derks C, Tudor D. Local treatment of pressure sores in the elderly: amino acid copolymer membrane versus hydrocolloid dressing. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994; 41: 1180–3

Seeley J, Jensen JL, Hutcherson J. A randomized clinical study comparing a hydrocellular dressing to a hydrocolloid dressing in the management of pressure ulcers. Ostomy Wound Manage 1999; 45(6): 39–47

Bale S, Squires D, Varnon T, et al. A comparison of two dressings in pressure sore management. J Wound Care 1997; 6(10): 463–6

Day A, Dombranski S, Farkas C, et al. Managing sacral pressure ulcers with hydrocolloid dressings: results of a controlled, clinical study. Ostomy Wound Manage 1995; 41(2): 52–65

Van Rijswijk L, Polansky M. Predictors of time to healing deep pressure ulcers. Ostomy Wound Manage 1994; 40(8): 40–51

Brod M, McHenry E, Plasse TF, et al. Arandomized comparison of Polyhema and hydrocolloid dressings for treatment of pressure sores. Arch Dermatol 1990; 126: 969–70

Tudhope M. Management of pressure ulcers with ahydrocolloid occlusive dressing: results in twenty-three patients. J Enterostomal Ther 1984; 11(3): 102–5

Hansson C, Cadexomer Iodine Study Group. The effects of cadexomer iodine paste in the treatment of venous leg ulcers compared with hydrocolloid dressing and paraffin gauze dressing. Int J Dermatol 1998; 37: 390–6

Ohlsson P, Larsson K, Lindholm C, et al. A cost-effectiveness study of leg ulcer treatment in primary care. Scand J Prim Health Care 1994; 12: 295–9

Arnold TE, Stanley JC, Fellows EP, et al. Prospective, multi-center study of managing lower extremity venous ulcers. Ann Vasc Surg 1994; 8: 356–62

Meredith K, Gray E. Dressed to heal. J Distr Nurs 1988; 7(3): 8–10

Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation. Apligraf (Graftskin) [product package insert]. East Hanover (NJ): Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, 1998

Lyon RT, Veith FJ, Bolton L, et al. Clinical benchmark for healing of chronic venous ulcers. Am J Surg 1998; 176: 172–5

Bowszyc J, Silny W, Bowszyc-Dmochowska M, et al. Comparison of two dressings in the treatment of venous leg ulcers. J Wound Care 1995; 4(3): 106–10

Smith BA. The dressing makes the difference: trial of two modern dressings on venous ulcers. Prof Nurse 1994; 9(5): 349–52

Van Rijswijk L, Multi-Center Leg Ulcers Study Group. Full-thickness leg ulcers: patient demographics and predictors of healing. J Fam Pract 1993; 36: 625–32

Teepe RGC, Roseeuw DI, Hermans J, et al. Randomized trial comparing cryopreserved cultured epidermal allografts with hydrocolloid dressings in healing chronic venous ulcers. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993; 29: 982–8

Cordts PR, Hanrahan LM, Rodriquez AA, et al. A prospective, randomized trial of Unna’s boot versus Duoderm CGF hydroactive dressing plus compression in the management of venous leg ulcers. J Vasc Surg 1992; 15: 480–6

Falanga V, Margolis D, Alvarez O, et al. Rapid healing of venous ulcers and lack of clinical rejection with an allogeneic cultured human skin equivalent. Arch Dermatol 1998; 134: 293–300

Field CK, Kerstein MD. Overview of wound healing in a moist environment. Am J Surg 1994; 167 Suppl. 1(A): S2–6

Ennis WJ, Meneses P. Wound healing at the local level: the stunned wound. Ostomy Wound Manage 2000; 46 Suppl. 1 (A): S39–48

Olin JW, Beusterien KM, Childs MB, et al. Medical costs of treating venous stasis ulcers: evidence from a retrospective study. Vasc Med 1999; 4(1): 1–7

Schonfeld WH, Villa KF, Fastenau JM, et al. An economic assessment of Apligraf (Graftskin) for the treatment of hard-to-heal venous leg ulcers. Wound Repair Regen 2000; 8(4): 251–7

Harding K, Cutting K, Price P. The cost-effectiveness of wound management protocols of care. Br J Nurs 2000; 9 Suppl. 19 S: S6–S24

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Donna Alexander for conducting the literature searches and obtaining the articles, and Gae O. Decker-Garrad for editorial assistance.

This study was supported by a grant from ConvaTec: A Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Skillman, New Jersey, USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kerstein, M.D., Gemmen, E., van Rijswijk, L. et al. Cost and Cost Effectiveness of Venous and Pressure Ulcer Protocols of Care. Dis-Manage-Health-Outcomes 9, 651–663 (2001). https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200109110-00005

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200109110-00005